13 – December 2018

clustered | unclusteredFashion folded into freedom

Otto von Busch

This season’s big fashion celebration during the New York Fashion Week marked not so much the arrival of something new as the curious celebration of fashion as an index of market saturation: the 50th anniversary of Ralph Lauren’s runway shows. Not only did the runway show impress with more than one hundred looks, the audience too was truly spectacular (and thus providing aesthetic legitimacy), including the go-to American fashion authorities, such as Donna Karan, Diane von Furstenberg, Calvin Klein and Kanye, as well as cultural icons such as Steven Spielberg, Oprah and many more. The show presented, as Vanessa Friedman, chief fashion critic of New York Times, points out, “haute patchwork gowns collaged together from scraps of tapestry brocade and velvet, dripping silk fringes at the seams, that summed it up best: a career as a collage of what once caught our collective imagination, refined over seasons.”1 Ralph Lauren’s show seemed like a manifestation of the total permeation of eternal remixes that today makes up fashion. It is the expression of freedom and diversity, presented with the accessibility of ready-to-wear.

Over the last decades we have experienced a ‘democratization’ of fashion, the mass proliferation of H&M, Zara, Forever 21, Boohoo and Asos chain stores or online markets. These mega-brands have become models of accessible and glamorous, on-trend fashion for the masses, with a multiplicity of styles almost individualized for each and everyone’s possible taste. And as if these chains were not broad enough by themselves, they additionally multiply into every niche of the market, such as H&M’s COS, And Other Stories, and Cheap Monday; a new brand for every income level and lifestyle. Fashion can sell every color of freedom at a cost close to zero.

This is what diversity looks like: now ‘everyone’ can participate in the pleasures of dressing according to the latest fashion, all seen on their ubiquitous social media feed. This model is sold to us as a fashion without any power hierarchies – as if the user is now in control simply because fashion is so cheap and accessible. Perhaps today, as fashion seems to have merged with social media’s continuous stream of updates, likes and hypes, fashion has amalgamated to become ‘free’: free as gratis, but also free as in freedom. Consumers pay nothing for the selfies, and only little for the skins they pose in. It all seems fair and just to the consumer buying yet another look of diversity for the cheap on the web. On a similar note, consumers don’t pay for fashion media anymore; the celebrities and new looks are all over the feeds. Everyone is free in the realm of fashion, and the more diverse, the more equal they are, the more democratic and just the system. And everyone can be beautiful now. “Because I’m worth it!”

The general tendency to relate cheap and accessible fashion to the notion of democracy perhaps highlights how disoriented most of us have become with the concept of democracy in general. It seems to denote something everyone engages in as they pick and choose between ready options, some cheaper and more disseminated, others elitist and exclusive. It equals a coalition of market and power, which is so natural it needs no explanation. Consumers do not really need to care much about their own voice in relation to it: on the marketplace of opinions, they simply need to pick and assemble an expression: a more engaged position of co-authorship is not really asked for. The table is already set, and everyone is invited.

Perhaps even Aristotle would have loved to go to the sales and get his look updated. As he mentions in the Nicomachean Ethics, “it is rather peculiar to think of the happy person as a solitary person: for the human being is a social creature and naturally disposed to live with others.” (IX.9) The wonder of fashion is that users are individuals and social creatures at once: We express ourselves, as it were, by dressing in mass-produced ready-to-wear garments that our peers also wear. We are unique and clone at once, solitary and social, happy and free, yet still locked up in the gilded chains of the chain-stores.

This insistence on the cheap and the accessible equates the freedom to choose between alternatives with a legitimate form of governing: no opinion or product is remote or inaccessible, as it is only a click away and delivered at a miniscule price. Freedom means the selection of cheap and user-friendly routes, offered to us with minimal friction. This is the apex of design as a guidance process; design as an invisible form of designation, of accessible routes of behavior where friction is minimized to the point of total disappearance. All routes seem open to us, all expressions and positions ready-to-hand, ready-to-wear: it has merged with our Being. We speed through the everyday with minimal strife or conflict, and click ourselves through our freedom, scrolling through the endless screens of cheap garments online, buying even if we don’t know if they fit or not. It is diversity and democracy and well-being, all at once.

If we then buy what is called ‘sustainable fashion’, or what H&M calls ‘conscious fashion’, we feel we are free and powerful at once. We are consciously doing the right thing, and we sleep better at night having made our modest contribution to save the planet. Yet, it seems the designated power in fashion works all the more unconsciously today: what seem to be free and well-considered decisions to make things right in practice operates to make our behavior undermine our intentions. What a consumer may experience as a ‘conscious’ choice of sustainability boils down to unconscious and unsustainable consumption. The current form of consumerism is the merger of material, economic, behavioral and psychological power, infusing our sense of freedom and identity under guided protocols, frictionless designations making sure we keep supporting the current chain-of-command at the level of the unconscious.

Designated power takes a specific form in the realm of fashion as most of us think of fashion as something we can all participate in. Through fashion we are simultaneously seeking superiority and equality; we feel in control of our looks, but in fact we are fashion slaves. We think our style is unique, but we are simple copycats. Through fashion we are simultaneously leader and follower, master and slave, producer and consumer. Somehow, we are all equal under the reign of fashion. And fashion is everywhere, we can have all these products at almost no cost, with no waste of time or negative impact – we experience total affirmation, total seduction, total desire. Ubiquitous fashion, the total embrace of democratic fashion, has folded itself into the social contract. Our sense of freedom has never looked better.

Freedom and equality tie in with the ideas of justice, and a fashion for all seems to be the justice of the mall. Yet, Karl Lagerfeld, the famous philosopher of fashion, posits in the documentary film Lagerfeld Confidential (2007) that fashion is “ephemeral, dangerous and unfair.”2 It is a statement that quite remarkably echoes Hobbes’ statement of life before the social contract as being “nasty, brutish, and short.” The social contract is not something abstract, it is something we live and practice every day. Cultural theorist Martha Nussbaum argues that social contracts “are not simply problems in academic philosophy. Doctrines of the social contract have a deep and broad influence in our political life. Images of who we are and why we get together shape our thinking about what political principles should favor and who should be involved in their framing. The common idea that some citizens ‘pay their own way’ and others do not, that some are parasitic and others ‘normally productive”, are the offshoots, in the popular imagination, of the idea of society as a scheme of cooperation for mutual advantage.”3

A social contract is the foundation of justice and its enforcement, and is built on an experience of mutual advantage. Under such a contract people still feel free, even if this vision can be distorted. An asymmetrical contract creates distortions of power and inequalities, friction and feud. A successful social contract has to be user-friendly and friction-free. It should somehow look diverse enough for enough people to feel part of it and strive to uphold the common order. As Nussbaum continues, “a contract of mutual advantage suggests that one would not include in the first place agents whose contribution to overall social well-being is likely to be dramatically lower than that of others.”4 Thus, if the contract looks diverse and accessible, it must be free and just, even more so if the market strives to also include the disempowered, the poor, the disabled, the weak and the plus-size. The more diverse fashion is, the more just, and the more free. As Nussbaum mentions, under a social contract the parts need to be free, equal and independent, that is, not subordinated to someone else (and not to fashion!). In other words, they should dispose of “equal powers and resources”,5 and they need to be independent, not under the domination of or asymmetrically dependent upon any other individual. If every consumer can access ready-to-wear freedom, isn’t this the fulfillment of consumer justice?

But as Nussbaum highlights, the central question on justice is: “who frames the principles of justice?”, and consequently: “For whom are these principles framed?”.6 Who is thus really in control of the diversity of fashion? Does diversity abolish the slavery of consumerism? Are more people really more equal, or have we just found an arena in which we think we can express ourselves freely, though we are just as powerless as before? Or, perhaps more poignantly, is the current model of diverse fashion the best freedom we can imagine? Can we today even imagine freedom beyond the shopping trolley? Maybe, we must start – in accordance with Robert Unger’s notion of ‘deep freedom’ – to imagine a new ‘deep fashion’ – beyond the formats of ready-to-wear politics.

So, in fact, Ralph Lauren’s celebratory runway exhibits a fifty-year evolution that turned counter-culture into a cool edge in the shopping cart, and folded the calls for freedom, diversity and justice into market opportunities. If you haven’t noticed yet, we’re living in a fashion utopia. Except for some collapsing factories here and there, which some ethical business models can easily fix, fashion convinces us with each new season that we live at the end of history; in the reality of fashion, the future of freedom is already fulfilled.

It all seems perfectly just and free now in the “haute patchwork” of accessible styles. The chaotic and heterogeneous expressions of Ralph Lauren’s work echo the diversity of our time. Freedom is folded into the field of accessible escapist consumer fashion. But as Vanessa Friedman poignantly states in the concluding lines of her analysis of Ralph Lauren’s show: “Ask not for whom the trolley bell tolls. It tolls for thee.”7

Notes

- 1 Friedman, Vanessa. “Ralph Lauren’s 50th Anniversary Show Was Eye-Popping. Then Came the Clothes,” New York Times, September 10, 2018, p. C8.

- 2 Lagerfeld, Karl. Lagerfeld Confidential, movie by Rodolphe Marconi, 2007.

- 3 Nussbaum, Martha. The Frontiers of Justice. (Cambridge: Belknapp, 2006), p. 4.

- 4 Ibd., 20.

- 5 Ibd., 29.

- 6 Ibd., 21.

- 7 Friedman, “Ralph Lauren’s 50th Anniversary Show Was Eye-Popping”.

a

clustered | unclusteredThe 8 Most Important Trends of the Spring 2019 Season

Ines Cox

1. The Greatest Escape

2. A Freer Kind of Ready-to-Couture

3. Must-Have Bolder Shoulders

4. 50 Shades of Beige

5. The Long and Longer of It

6. The Handmade Tale

7. Bye-Bye, Basic Black

8. Some Like it Hot

b

clustered | unclusteredLe spleen de Paris

On Fashion, Sex and Dance Underground

Thomas Meinecke

If it were up to me, I would like to see any writing of history that leads us to contemporary club culture begin in the brightly gas-lit shopping arcades of urban Paris at the dawn of the modern Bohemian era, when Charles Baudelaire, already endowed with the intensely nervous power of perception of a male hysteric, extolled—in a libidinously degenerate l’art-pour-l’art sophistication—an until then unheard-of artificial paradise (Les fleurs du mal) and allowed himself to become intricately intoxicated by the pulsing anonymity of the metropolitan masses (“À une passante”), just as Edgar Allan Poe (“The Man of the Crowd”), later translated by Baudelaire, had already demonstrated shortly before on the other shore of the Atlantic blackened by colonialism in Baltimore, Richmond, Philadelphia, and New York.

Hence: The Birth of the Flâneur out of the Spirit of Literature

We might also glance over the shoulder of Walter Benjamin in his Parisian exile while fleeing from the Nazis, who reflects Baudelaire’s inquisitive look at these then only-just-emerging myths of everyday life, for example drugs and makeup, in his epochal Passagenwerk, or Arcades Project, which for me marks the beginning of the discursive modern pop era. The West German music critic Helmut Salzinger correspondingly published a paperback called Swinging Benjamin, which did the rounds in pop culture circles in the 1970s.

At the time, controversial disco music was beginning its glittering and triumphal international advance against rock music’s macho, phallus-centered claims to authenticity, leading rock to deride disco as “sissy music.” This culminated in 1979 in the deadly Disco Demolition Night, when all the people attending a mass sports event in Chicago’s Comiskey Park Stadium were asked to bring along disco records, which were then piled up between games and blown up. The whole thing turned into a riot, and no second game was played, but, supposedly, starting the next day, no more disco music was played on mainstream American radio. And rock once again reared its ugly head.

Now, however, disco, despite its easy, superficial comprehensibility, was actually an elaborately coded affair, whose development was indebted to processes of re-signification and re-contextualization: the higher art of camp, which made it possible for an entertainment commodity rolled out for the middle class (for instance, the golden swing standards for which parents had attended dancing lessons) to be read against the grain from a partisan perspective and put in a new, sexually dissident light. What bebop had also already done with the same starting material in a magnificent deconstruction of African diaspora, in a distinctive signifying that was stylistically somewhat more mysterious than in the case of disco: Charlie Parker turned How High the Moon into Ornithology, which defied recognition and was appreciated first of all in Paris.

Whereas disco also had a role model shaped by the appropriation politics of the Lavender Underground: In Charles Ludlam’s Theatre of the Ridiculous genre or in Flaming Creatures by Jack Smith, who, in his apartment on the Lower Eastside set up large-scale, semi-Catholic altars for third-class Hollywood divas such as María Montez, to then have these divas play in his own underground movies by Mario Montez, who later became an Andy Warhol superstar, and, in Berlin on November 1 a few years ago, gave me an autograph, which he dated “All Souls’ Day.”

God Rest Mario Montez’s Soul

In any case, disco culture did not trouble itself further about the homophobic machismo of the rock mainstream and went into the underground with its head held high, turned under the asphalt into pre, proto, and finally true house, made stops in temples such as New York’s Paradise Garage, where DJ culture found fantastic expression, but also in catacombs concealed under the asphalt of Chicago’s South and West Side, the entry holes to which were known only by those initiated into sexual dissidence. Techno in Afro-American Detroit was also anything but street and was instead generated invisibly, below the surface, from the depths of the “Black Atlantic,” or rather the vastness of space: the band Underground Resistance (and, namely, in an adventurous, transatlantic closing of ranks against the hostile white Anglo-Saxon Protestant society of the United States with the assistance of ambiguous-to-cutthroat Teutonic technology: Afrogermanic). A visionary term for the highly charged instrumentals of this new direction in musical style: Black Secret Technology. This is a political statement. Afrofuturism as a form of expression for civil rights that had never truly been granted.

The African diaspora experience as an experience produced by dislocation, from Delta blues via minstrelsy, ragtime, various jazz styles, R&B, and P-Funk, to hip hop and techno, always the most complex, decidedly eccentric forms of music (and with juke and / or footwork music from Chicago, we have another brilliant example of the ongoing intelligence of the African-American ghetto).

Night Owls

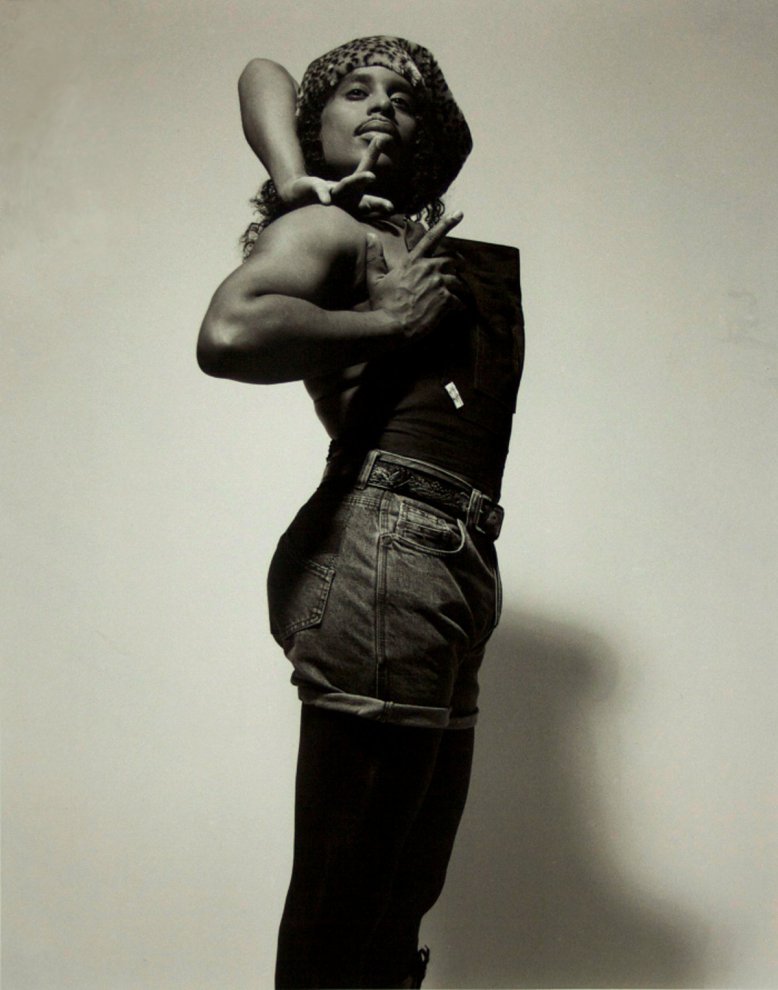

As far as the aspect of performativity is concerned, on African-American terrain, we also find countless pioneering “role models” for the diverse queer nightlife that also increasingly pushed its way into a street scene flooded by daylight: from Frankie Half Pint Jaxon to Little Richard, Sylvester, Michael Jackson, and Prince—to likewise name two artists who are also guided by heterosexual desire, but whose heteronormativity is refracted in flamboyant beauty—to RuPaul or currently Mykki Blanco. From this, particularly in the predominantly Latin American and thus Catholically coded backyard ballrooms of Spanish Harlem, the subcultural high culture of voguing developed—long before Madonna helped it gain mainstream popularity with her hit of the same name.

Also once again here: ideas not accepted by society are brought to realization on improvised catwalks in a hedonistic overstepping of fixed categories such as race, class, and gender: female top model, dapper schoolboy, influential banker, dandified army general. The key category in this: realness (you make me feel mighty real as one of the central slogans of disco music).

Me as Fag Hag (The Gayification of the World)

When I attended a memorial for the recently deceased superstar of voguing, Willi Ninja (who, on his part, was influenced by Fred Astaire on afternoon television, and also taught Paris Hilton how to perfect her walk) at New York’s Cielo Club in 2006, and all the legends of this culture with whom he had been friends, including their moms and pops, who enthusiastically captured everything in photos, watched Kerri Chandler perform on the decks, I felt reminded of the Symbolist scenarios acclaimed by Charles Baudelaire in Le Spleen de Paris (and was moved to tears). Paris Is Burning is then also the title of Jennie Livingston’s documentary film of 1990 about the profoundly inspired, voguing ballroom culture of Spanish Harlem, which Judith Butler refers to quite centrally in her academic exploration of its epochal, path-breaking deconstruction of supposed masculinity and femininity (Gender Trouble), which also made clear to me that I am not simply a man (but rather doing being one).

Living in Beauty

Things are not that much different, for instance, in clubs in Baltimore, with gigantic champagne bottles painted on their metal shutters.

Around 1990, a central construction site for what we today know as club culture also came into being: Berlin as a place (comparable with the bebop events of the past in Paris) for a fruitful transatlantic feedback full of mutual respect between the music producers of a postindustrial Motortown and those of a German capital that had been fragmented until a short time before.

The rest is present.

c

clustered | unclusteredMovement governs the [Fashion] event

Marylaura Papalas

What do contemporary fashion shows tell us about clothing, women’s roles in society, and the dynamics of female solidarity? Cynthia Rowley’s roller derby presentation of her Spring 2019 collection this past NYC fashion week was revealing, mainly because it was on wheels. The careening speed harnessed by the roller-skating female models was the most distinguishing feature of the show, and insisted that strutting down a catwalk is not necessarily the most exhilarating or entertaining way to present a collection. The unbridled performances of the models (many of whom were not professionals but seasoned roller derby players) is reminiscent of the excitement in descriptions of Elsa Schiaparelli’s legendary Circus Collection show from February 1938, where the models and performers, recreating the big-tent atmosphere, supposedly leapt across the designer’s “dignified showrooms,” creating one of the most memorable spectacles in fashion history, and as I have argued elsewhere, facilitating a carnivalesque and virtual trip to another place.1

The skaters’ performance similarly created an alternative world of accelerated motion, racing wheels, and billowing garments floating past the spectators. If the blurred bodies generated an ethereal feeling, they also reflected the idea that women supporting women and working together as a unified collective result in a positive experience. Because Rowley’s skaters interacted with each other and sometimes with the audience, ignoring the theatrical barrier and restrained decorum that dominate most fashion shows, they modeled the female comradery encouraged by the #MeToo movement. Supporting each other and galvanizing those in their wake, these women celebrated female empowerment and the freedom to move, exist, and define their own femininity. They also channeled an uninhibited and unabashed determination to cajole and have fun. They rallied around one another, cheered each other’s skate moves, and unleashed the pure joy of celebrated feminine power. Rowley’s skaters captured the bravery, hope and momentum that the #MeToo movement is giving women, and their speed and velocity magnified those optimistic messages.

The power of speed is the subject of a number of theoretical works, primary among them being Negative Horizon (1984) by Paul Virilio, who inspired the title of this article.2 Virilio describes how acceleration is a means of human empowerment, and he provides examples from history, many of them tragic, where exploited speed leads to an overtaking and/or mistreatment of another group. Colonialization, for example, and its access to modern forms of transportation and information technology, enabled colonizers to move people, segregate them, and even exercise violence on them. “To gain speed is always to take power”.3

Rowley’s roller women offered a feminized narrative of speed as empowerment. Instead of exploitation, they genderbent velocity in order to liberate themselves from social restrictions, professional codes of conduct, and traditional ideas about performed style. The ethnically diverse group, with a range of body differences, exhibited the kind of inclusive and accepting world where many of us strive to live. The speed with which these women zipped and danced down Morton Street and into the designer’s Manhattan studio facilitated a reimagining of the fashion show’s function, reminding us that women presenting fashion have the potential to change it, as well as the world around them.

Notes

- 1 Marylaura, Papalas. “Fashion in Interwar France; The Urban Vision of Elsa Schiaparelli,” French Cultural Studies 28, No. 2 (May 2017): 159-172, here: 167-168; Palmer White, Elsa Schiaparelli: Empress of Paris Fashion (New York: Rizzoli, 1986), 166.

- 2 Paul Virilio, Negative Horizon: An Essay in Dromoscopy, translated by Michael Degener (London: Continuum, 2005), 104.

- 3 Ibd., 58.

d

clustered | unclusteredPoet-Tees. A Crowdsourcing T-Shirt Poetry Experiment

Naomi Lubrich

Fashion week is people watching week. As a scholar of literature, however, my eyes drift towards the text of fashion – the statements on bags, the slogans on T-Shirts. Last year’s messages were political. Prabal Gurung cast his words in black on white and white on black: “I AM AN IMMIGRANT”. “THE FUTURE IS FEMALE.” “WE WILL NOT BE SILENCED.” And: “LOVE IS LOVE.” This year, the statements appear to be more subdued. Dior asks, “Why have there been no great women artists?” citing the title of a book by art historian Linda Nochlin. Many others have no clear reference, such as Victoria Beckham’s shirt, claiming a “Fashion Emergency.”

Moving from professionals to the public, T-Shirts are no less telling. Whether people choose their clothing intentionally or subconsciously, their statements are a reflection of the zeitgeist. The messages can be surprisingly atmospheric. We learn what people feel about what they are doing on any given day, if not on individual T-Shirts, in their combinations. So what do strangers, grouped by chance and circumstance, tell us?1

Airport

Basle, 13 July 2018

Jack & Jones Explore the Blue Arctic Outdoors.

Blue Seventy Northeast Sailing Crew.

Bison Wildlife district.

Darkest Hour.

Follow your instincts.

Live to Thrash. Thrash to live.

Just do it.

Tommy Jeans, Orange Rangers, Uncle Sam, vote remain.

Mini Cooper. See something super.

Frisco Baseball, Burton Durable Goods.

Originals Surf.

South Beach. Ride out the Heatwaves South

Cruise Ship

Bremerhaven, 20 July 2018

Diesel for successful living

– Powered by Dyff

Start your day with positive thoughts

Surf

Love

Keep life simple

Supercool holiday come on

San Francisco Authentic, Candyfornia Babe

Fitch New York, The city that never sleeps

Tokio Superdry Japan

Hard Rock Café Athens/Chicago

Orig. Camp Bavio

Amsterdam

Norway

Just do it, TRA VEL LER

Don’t grill my vibe, Black Squad,

Don’t push my buttons, NYPD

Chic happens (Paris, France)

Born to inspire Good mood

TRUE

Dancing Competition

Fribourg, 8 September 2018

Alissia, Helena, Arnaud, Margot, Isabelle, Rebecca

young Giorgio di Mare and sons

ready to be happy

Dancing out of line

Etoile, The Flash, no limits

Dream: all star converse

Wingardium leviosa!

Guess the color run

Put yourself first?!

Swipe. text. block. repeat

Tap, I heart tap

This is yoga, Backstage studio, Classic havana Club, Spain

Everything will be fine, Cats.

Notes

- 1 In three cities, on three occasions, I wrote down the words people wore on their clothing, arranged them and added only punctuation. The result is crowdsourced T-Shirt poetry.