84 — November 2022

#BlackGirlMagic in contemporary South African literature

Nedine Moonsamy

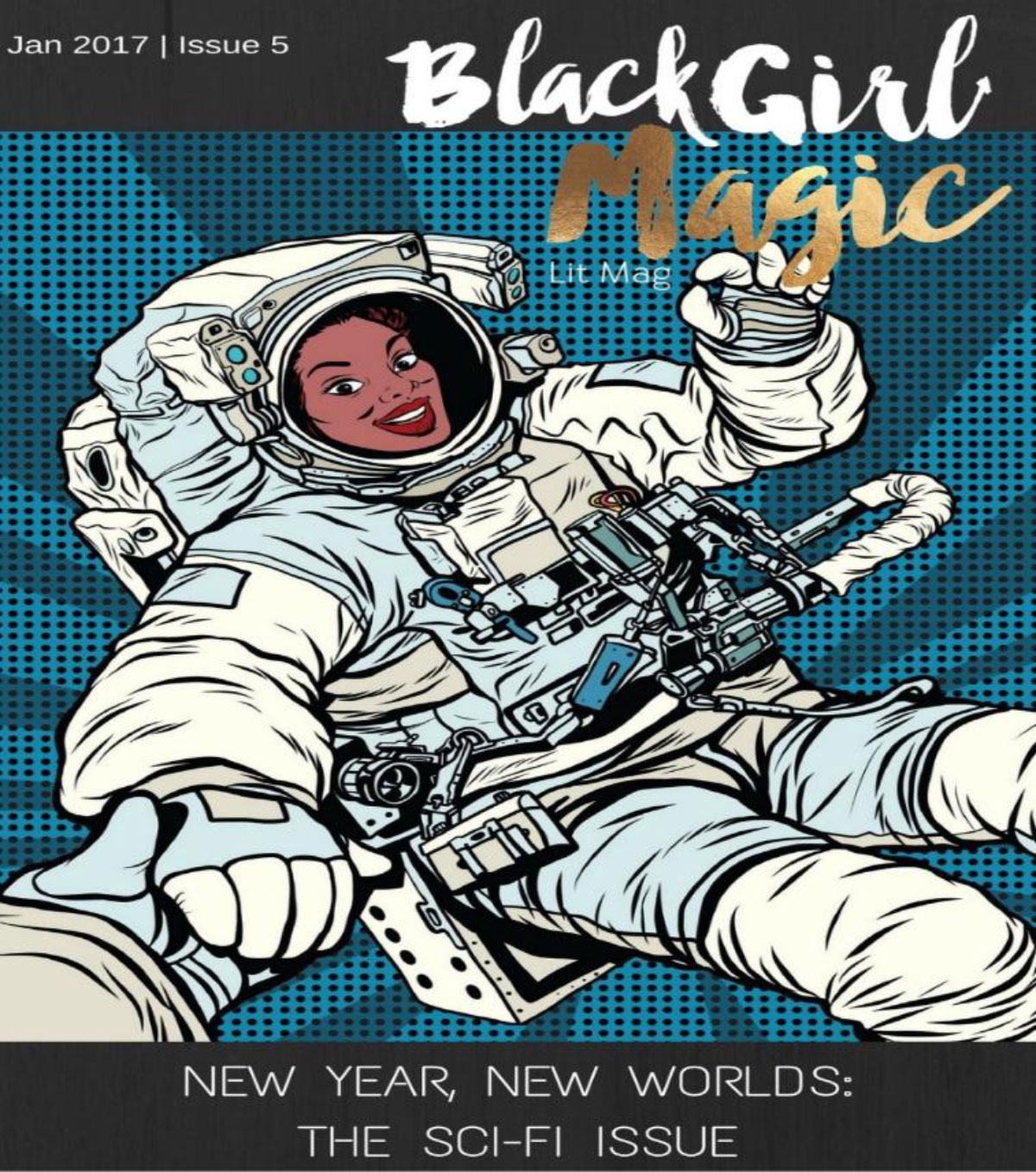

Coined by Cashawn Thompson in 2013, #BlackGirlMagic is an affirmative Afrofuturist spin on black women’s identities in popular culture. According to Briana Nicole Barner, using the word ‘girl’, as opposed to ‘woman’ signals at the redemptive nature of this hashtag, as black women use it to address and honour their younger selves who struggled through the often traumatic minefield of black girlhood.1 And so, celebrating themselves as grown women, they acknowledge their strength, courage, and accomplishments through SF tropes like magic and fantasy, which then, as we see in Karissa Tolliver’s image, Black Girl Magic Pass It On (pictured below), grants permission to other black girls to bear witness to the cosmic wonder that resides within. By encouraging the circulation of images of this kind, the hashtag seeks to open up the imaginative realm of possibilities for black girls to see and understand themselves as valued, extraordinary and special.

In this regard, #BlackGirlMagic draws on the more optimistic tenor of Afrofuturism. In ‘Quantam Blackanics’, John Murillo III argues that because linear, earthly time is antiblack, black identities can benefit from exploring the correlation between blackness, quantum physics, and time travel instead.3 Seeing that systemic and historical dehumanisation has rendered African American life post-apocalyptic at the outset, Afrofuturism thus uses SF tropes to give expression to this sense of alienation and disembodiment. Rather than seeking to recover forms of wholeness, Afrofuturism directs its gaze to the potential embedded in alternative space-time dimensions. In this way, Afrofuturism converts the perceptions of being subhuman into that of being superhuman by grasping at the largesse and wonder of the otherworldly. It brings together the odd assemblages, surreal selves and the rapturous awe of the fantastic as a celebration of ontological potentialities for a someone and somewhere beyond the here and the now.

Though primarily an American phenomenon, #BlackGirlMagic has found some resonance in spaces like South Africa. Yet in two South African books, Unathi Magubeni’s Nwelezelanga: The Star Child4 and Buhle Ngaba’s The Girl Without a Sound5, an ambivalent portrait emerges. Nwelezelanga, which we could consider as young adult fiction, is about a young albino girl who is abandoned by her mother, who is a dark witch. But Nwelezelanga is found by a kind woman who adopts her and loves her as her own child. When Nwelezelanga’s spiritual and magical talents start to emerge, and she grows into a powerful healer in her new community, her estranged mother soon becomes aware of her power. Fearing her light, her mother attempts to kill Nwelezelanga, but darkness does not prevail and Nwelezelanga unleashes her magic to restore balance in a troubled world.

Ngaba’s The Girl Without a Sound is a children’s book where an imaginative little girl lives in her fantasies because she cannot speak. One day, a magical character called the Red Llady from the moon appears, and together they have a series of wonderful adventurestogether. As a result of these excursions, the little girl learns from the Red Lady that she has magical powers, but needs to find her voice in order to unlock it. In each of these narratives, magic is not bestowed on these young girls, it is an inherent feature of their being that is simply brought to their awareness over time.

Yet while their magical abilities set the main characters apart as special, Nwelezelanga and The Girl Without a Sound also draw an inextricable link between magic and conditions of trauma. For example, Nwelezelanga must overcome both the social stigma of albinism and the pain of her mother’s abandonment, and the little girl in The Girl Without a Sound has completely lost her ability to speak. These characters also share a common inability to cure trauma within the empirical context of the subject; the answers are always beyond the reach of reality which then leads to the recourse to magic. Arguably, magic serves a narrative ruse, distracting from the often inescapably violent circumstances that black girls live in, thus leaving room to rethink the extent to which #BlackGirlMagic achieves its aims.

Nnedi Okorafor has also critiqued the alleged empowerment that comes with typecasting black characters as inherently magical. Turning to the trope of the magical negro in various literary texts and Hollywood moviescinema like The Green Mile (1999), Okorafor notes how this figure marks “the subordination of a minority figure masked as the empowerment of one. The Magical Negro has great power and wisdom, yet he or she only uses it to help the white main character; he or she is not threatening because he or she only seeks to help, never hurt.” 6 Okorafor continues by arguing that due to a history of primitivism, the “magical Negro was simply how the writers of the stories viewed black people. That to them, in a way, blacks were like robots (or slaves), put on the earth to help white folks. That like Asimov’s robots, black people had rules imprinted in their brains that made them so selfless.”7 Similarly, in Physics of Blackness, Michelle Wright notes that it is “mystique, which lifts the body up in the white imagination”,8 and in Playing in the Dark, Toni Morrison is equally critical of this literary trope as it appears in Mark Twain’s Huck Finn.9 Morrison highlights how Jim serves a benevolent sounding board to Huck, but is never given equal regard in the consideration of his personal freedom. These thinkers help us to reconsider how the association between blackness and magic often signals at the marginality and the dehumanisation of black characters in a white world.

Similarly, Sandra Jackson condemns the Alien versus Predator enterprise for its depiction of black female exceptionalism and, as a result, its corresponding sense of profound alienation. She recalls being initially enthusiastic about the fact that a Hollywood franchise made the bold choice to cast a strong black female as a protagonist. And it is with added glee that she notes

that the black woman warrior had survived. But I was not so sure that she was in an enviable place. Not sure that her survival was laudatory […] she was stranded on some uninhabited planet or meteoroid, probably light years away from contact with others or a rescue team. Out of contact with other humans, with only the stars for company.10

Jackson cannot understand why there is no space for this lead character to peaceably return home after her heroic journey and to exist as a social being among her community.

Writing in response to #BlackGirlMagic, Linda Chavers opines that it feeds into the stereotype of the ‘Strong Black Woman’ whose body feels no pain and whose struggles must be endured with heroic fortitude.11 As someone who lives with a chronic illness, Chavers feels that the label excludes black women like her who wage a constant battle against pain and a suffering body. As we see in Nwelezelanga: The Star Child and Buhle Ngaba’s The Girl Without a Sounddiscussed here, #BlackGirlMagic cultivates courage, but also glorifies the need to continually persevere in a hostile world, all the while using magic as a distraction from a lack of real-world solutions to ongoing pain and trauma. As critics like Sylvia Winter argue, for people who have never been recognised as human, the idea of posthuman identities offers little to no reprieve. 12 And so, one is left to wonder about the possibility for black women to find more mundane forms of expression in popular culture, forms that don’t require them to be as extraordinary – as magical – as this.

Notes

- 1 See Barner, Briana Nicole. “The Creative (and Magical) Possibilities of Digital Black Girlhood.” MA Thesis, 2016, https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/bitstream/handle/2152/39439/BARNER-THESIS-2016.pdf.

- 2 Found at https://fineartamerica.com/featured/black-girl-magic-pass-it-on-karissa-tolliver.html

- 3 See Murillo III, John. ‘Quantum Blackanics: Untimely Blackness, and Black Literature Out of Nowhere’, 2016. Ph.D Thesis. Found at, https://repository.library.brown.edu/studio/item/bdr:674359/

- 4 Magubeni, Unathi. Nwelezelanga: The Star Child. BlackBird Books, Johannesburg, 2016.

- 5 Buhle Ngaba’s The Girl Without A Sound, found at ‘Buhle Ngaba’, 2016. https://buhlengaba.com/portfolio/the-girl-without-a-sound/

- 6 Okorafor, Nnedi, “Stephen King’s Super-Duper Magical Negroes”, Strange Horizons, 25 OCTOBER 200425 October 2004. Found at: http://strangehorizons.com/non-fiction/articles/stephen-kings-super-duper-magical-negroes/

- 7 ibid

- 8 Wright, Michelle M. Physics of Blackness: Beyond the Middle Passage Epistemology, University Of Minnesota Press, 2015, pg. 1.

- 9 Morrison, Toni. Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination. Vintage Press, 1993.

- 10 Jackson, Sandra. “Terrans, Extraterrestrials, Warriors and the Last (Wo)man Standing.” African Identities, vol. 7, no. 2, 2009, pp. 238.

- 11 Chavers, Linda. “Here’s My Problem With #BlackGirlMagic”, ELLE, 2016. https://www.elle.com/life-love/a33180/why-i-dont-love-blackgirlmagic/

- 12 Wynter, Sylvia. “Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom: Towards the Human, After Man, Its Overrepresentation—An Argument” CR: The New Centennial Review, vol. 3, no. 3, 2003, pp. 257-337.