33 – April 2022

clustered | unclusteredKeeping (War)time

This cluster is launched on the 37th day of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. It is launched from Belgium, where the brutalities and horrors of the war are—incredibly, unavoidably—already drifting away from the focus of public attention. (Today, the television news opens with reports of unexpected snow and speculations about the flu-like symptoms of a cyclist.) All of this is understandable: there is only so much distant suffering that can touch us. All of this is unforgivable: there is no moral justification for losing interest when lives continue to be wasted. Finding a proper perspective while war is raging is an assignment that is as impossible as it is unavoidable.

Collateral turns to the realities of war in the conviction that keeping them into focus is a condition for calibrating our distance or proximity to them. It would be disingenuous to claim that we, launching this journal from Belgium, are at war—are in a time of war. Which is not the same as wartime: as literary critic Mary Favret has explained, “wartime” names a condition in which everyday life goes on while we know war to be waged elsewhere—a war in which we don’t participate directly, but which yet intermittently pierces our customary lives—through the images on our screens, the suffering in our timelines, the fluctuations in our asset portfolios, the refugees on our doorsteps. The time and feel of wartime is complex, contradictory, and provisional—which should not tempt us to assume that the time and affect of war is ever simple.

Collateral has decided that this affective and temporal complexity called for something unprecedented: a continuous cluster, in which four writers and artists will share visual and/or textual contributions in weekly updates. Cumulatively, these contributions will keep (war)time and remind us of the brutalities of war: they will provide insights and experiences from very diverse perspectives to measure up to a reality that is as ephemeral as it is inescapable. The only rigorously unmethodological method we could imagine for conveying these dimensions, for keeping them in focus from different positions, is by clustering very different contributions—literary as well as artistic, poetical as well as visual as well as testimonial, and, most importantly, impossibly and unavoidably, both Ukranian and Russian. Two of our contributors report directly from Ukrain—from the time of war—two others measure the difference between wartime and the time of war. It is only their overlapping imaginations that keep the reality of war in focus—also on the 38th day, and after.

About the authors

Danyil Zadorozhnyi (1995, Lviv) is a Ukrainian poet and journalist who writes in Ukrainian and Russian. He graduated from the University of Lviv (Faculty of Journalism) and has lived in Simferopol, Kyiv, Kharkiv, Zelenograd, and Minsk. His poems have been published in Los Angeles Review of Books, Words Without Borders, Litcentr, Tsirk "Olimp"+TV, polutona, and Gryoza, among other forums. In 2019, Zadorozhnyi obtained the A. Dragomoshchenko Poetry Award (2019). In 2016-2017, he was a finalist of the Smoloskyp Poetry Award (2016-2017), and in 2018, he was longlisted for the Gaivoronnya Award. He’s the author of the bilingual poetry book Nebezpechni Formy Blyz'kosti ("Dangerous Forms of Intimacy", Dnipro: Gerda Press, 2021). Danyil's poetry is translated by Yuliya Charnyshova (1998, Minsk). She is a poet who is also engaged in literary projects as a translator and an editor. She is currently is based in Lviv, Ukraine. At the moment, she is a (remote) graduate student in the Russian Literature in Cross-Cultural Perspective program at the HSE University, St. Petersburg, where she's researching twentieth- and twenty-first-century Slavonic and Anglophone poetry. Her translations appeared in the Los Angeles Review of Books and Words Without Borders (both co-translations — with Elina Alter and Isaac Stackhouse Wheeler), as well as in F-Pismo journal. In 2021, she edited Zadorozhnyi’s book Nebezpechni Formy Blyz'kost.

Anyuta Wiazemsky Snauwaert (1989, Moscow) is a multimedia artist, photographer and curator. She graduated from Law Academy in Moscow in 2011. Since 2013 she lives and works in Belgium. She studied Fine Arts at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Ghent. Her works have been shown in a.o. Amsterdam (NL), Antwerp (BE), Brussels (BE), Ghent (BE), Hyderabad (IN), Moscow (RU), Murcia (ES), and Rotterdam (NL). She is interested in the interaction between aesthetic experiences and the banality of everyday life, which emerges all the more when presenting art in unexpected environments or, vice versa, when conducting an “ordinary” activity in an art-related context.

Daniil Galkin (1985, Dnipropetrovsk) is a contemporary Ukrainian artist and curator. He studied at the Dnipropetrovsk Theater and Art College and the Academy of Civil Engineering and Architecture. He works with public space, using spatial installations, happenings, subject-oriented art, etc. He collaborates with state and municipal art institutions, drawing attention to objects of Soviet heritage. He founded the independent NGO Pridneprovskiy barvinok (2018) and the exhibition space "Barvinok Art Residence” (2020). He is the winner of the Grand Prix MUXI in 2011, the Third Special PinchukArtCentre Prize in 2013, the Special Art Future Prize in 2020; he was shortlisted for the PinchukArtCentre Prizes in 2011, 2013 and 2015, and for the Kuryokhin Prize and the Kandinsky Prize in 2012. He was a finalist of the Malevich Award in 2014 and the M17 Sculpture Prize in 2020. His work was on display in solo and group exhibits at international venues, such as Gangwon International Biennale 2018 (Gangneung, South Korea), Silent Barn Gallery (New York), KW Institute for Contemporary Art (Berlin), Saatchi Gallery (London), Kunsthal Charlottenborg in Royal Danish Academy of Art (Copenhagen), Artspace TLV (Tel Aviv), Open Studios (Beirut), Danubiana Meulensteen Art Museum (Bratislava), CzechCentre (Prague), National Art Museum of Ukraine (Kiev). He was also a resident of Künstlerhaus Lauenburg/Elbe (Lauenburg), Gaude Polonia (Byalistok, Warsaw), Bogliasco Foundation (Genoa), 40mcube (Rennes), BeirutArtResidence (Beirut), and Forum Regionum (Dnipro).

Masha Ivasenko (1984, Moscow) graduated from the University of Ivanovo with a degree in Philology, and obtained her master’s degree in Arts and Humanities at St. Petersburg University. She has been working primarily as a teacher. Since September 2021, she's been living in Hasselt, Belgium. Her research interests are cinema, contemporary art, political philosophy, and psychoanalysis.

a

clustered | unclusteredDanyil Zadorozhnyi

09 / 05 / 2022

Yet Again, There is Poetry

(transl. Yuliya Charnyshova)

Yet again you have spread the sand all around the house, ‘cause you walk in and you walk out all of the time, fetching some water, and then you fall asleep in your shoes. Yes, everything feels like you’ve just stayed here for a couple of years, no more than that. You were living here without knowing that something was moving toward you. You didn’t watch the crack as it’s been appearing, how it walked the wall of the building. You didn't think you wouldn't be able to leave once you sense danger. I have no chance to think about any poetic periods—now everything is so inappropriate— except for the war. Yet the war in itself is also so inappropriate, the most inappropriate of all things, the most untimely and useless. Although I would very much like to think about what I was thinking about before February 24—and yet there is war that has begun. On a full scale. Well, as a matter of fact, it has been going on since 2014. It’s becoming harder to explain this to foreigners. It is hard to keep it in mind and harder to live it with each year. To know now that while their troops are attempting to take Mariupol again, judges in Kyiv are taking bribes yet again. There are builders, dismantling historical heritage despite the martial law in Kyiv, emptied by war. Well, at least it is builders, not bombs. If Russians were there. You imagine yourself and your loved ones in such a place. If Russians were there. How quickly would they start shooting and all that? * Nowadays, there is no point in convincing those who support the war, who justify it, but on whom no decisions depend, who have sold their agency as if it was a soul. I don’t have the energy for that. And the decisions of those who control the regime, the discourse, and a nuclear weapon will depend on the type of resistance that happens at the front. It’s just a situation like this—where we cannot surrender.

Вкотре (поезія)

знов розніс пісок по всьому дому бо ходиш-ходиш по ту воду, а потім спиш у взутті, так, наче зупинився тут на кілька років, не більше. жив тут і не знав, що на тебе щось рухається, не дивився, як стіною будинку йде тріщина, не думав, що не зможеш виїхати, якщо відчуватимеш небезпеку. у мене немає можливості думати про поетичні періоди, зараз все таке недоречне — крім війни. і сама війна теж вкрай недоречна, найнедоречніша із речей, найневчасніша і найнепотрібніша хоча дуже хотілося б думати про те, про що думалося до 24 лютого — а тут війна почалася. повномасштабна взагалі-то, вона триває з 2014 року. дуже складно пояснювати це іноземцям. складно тримати це у своїй голові та жити у цьому щорічно. знати зараз, що поки вони знову беруть маріуполь — судді у києві знову беруть хабарі будівельники зносять історичні пам'ятки попри воєнний стан у спорожнілому києві хоча б не бомбами, як росіяни уявляєш себе та своїх близьких на тому місці, якби і сюди прийшли росіяни як швидко вони б почали розстрілювали та все таке інше?. * якщо чесно, то зараз немає ні сил, ні сенсу переконувати тих, хто підтримує цю війну, хто виправдовує її, але від кого вже не залежать ніякі рішення, хто віддав свою суб'єктність як душу а рішення тих, хто керує режимом, дискурсом та ядеркою залежатимуть від боїв на фронті це така ситуація, де ми не можемо здатися

22 / 04 / 2022

Not thankful but sorry

(transl. Yuliya Charnyshova)

not thankful but sorry to stay alive in the relative safety of sealed windows in western cities. heating on, there’s food, Internet, and we’re not under siege. while in Mariupol they’re taking delight in seeing snow, knowing it can be collected in a basin and drunk in between ceasefire violations and an attempt to evacuate. and after almost two months of occupation, I just want to shout about it because no one can hear or do anything. trying to break through the enemy lines with our helplessness, paving the way, a humanitarian corridor made of the enemy’s prayers, phone calls to their wives and corpses. sorry for being lucky not to be in the wrong place at the wrong time, not to be born in their way, in the mind of his plan to capture us all. us, anxiously waiting, weaving a camouflage net or assisting resettlement of refugees at the railway station. in a reflective vest that a volunteer took off her sleepless shoulders. she’s having dreams about downpours of shells being dropped on Sheptytsky Hospital, in which Ivan Franko has died. the country needs all of it, this too [can you write poetry after what happened?] poetry just like language can be there after anything just not for everyone and you too cannot stand it right now hating it for being untimely

не дякую, а вибачте, що лишився живим у відносній безпеці заклеєних вікон західних міст у теплі, з їжею, інтернетом та не в облозі поки в Маріуполі тішаться снігові, бо його можна зібрати в таз та пити між порушеннями тиші та спробою евакуації а після майже двох місяців окупації хочеться просто кричати про це бо ніби ніхто не чує й не може нічого вдіяти з безсиллям проривати оточення у вашому напрямку проклавши гумкоридор з їхніх благань, дзвінків до дружин та трупів що пощастило не опинитись не в тім місці, не у той час не народитись на їхнім шляху в голові його плану захоплення тривожно чекаючи за плетінням сіток та розселенням біженців на вокзалі у світловідбивній жилетці з невиспаного плеча волонтерки зі снів про зливу снарядів на шпиталь шептицького в якому помирав франко це також потрібно країні поезія як і мова можлива після будь-чого просто не для всіх й ти також її зараз не хочеш зненавидівши за невчасність

15 / 04 / 2022

Can't promise you much

(transl. Yuliya Charnyshova)

you ask me whether everything is going to be alright with us, will we be okay? and I answer that yes, we surely will, although you know that I can't promise you much just like I cannot leave the country. we’ve talked it all through, and you remember that because that’s where we live and now you’re living here too and there’s russia, invading our home like a knife through the body of belarus but look at the east of ukraine right now, look farther and closer in our house, we’ve gathered so many things in one place near the doorway, both most important and not important at all, money, medicine, and clothes we’ve moved furniture to free up some space we’re now hosting people from the rest of ukraine everything's different and we could never get used to it, but we are getting used to it. though it's not about me. it’s all about listening to what people who survived the invasion are saying, in what languages are those people talking? come and see and listen I can't listen to it, for so long, it’s too much, but it’s what we need to know and remember what happened, sluchilos'1 or trapylosʹ2 to us because of them/you but you seem to be calmed by me saying it’s gonna be alright so I’m happy to see you find something comforting though I don’t like to say that everything is gonna be fine, especially when in fact, everything’s fucked and it’s gonna get worse

ты спрашиваешь, все ли с нами будет хорошо, все ли будет в порядке и я отвечаю, что да, конечно будет, хотя ты знаешь что я не могу обещать тебе этого так же, как не могу уехать мы проговорили все это, ты помнишь потому что живем здесь и ты теперь здесь живешь и россия вторглась в наш дом ножом сквозь тело беларуси но смотри на восток украины сейчас, смотри дальше и ближе мы собрали самые важные и неважные вещи в одно место у выхода как деньги, медикаменты, одежда передвинули мебель, освободив место принимаем людей из остальной украины все стало совсем по-другому и невозможно привыкнуть, но привыкается но это не обо мне. важно слушать не меня, а то, что рассказывают люди, выжившие после оккупации на каких языках? смотрите и слушайте я не могу это слушать, так долго, так много, но необходимо знать и помнить что было, случилось і трапилось з нами из-за вас но тебя успокаивает, когда я говорю, что все будет хорошо и я рад, что тебе от этого спокойней хотя сам не люблю говорить, что все будет хорошо. особенно когда на самом деле все очень хуево и будет еще хуже

08 / 04 / 2022

Ukraine. War. Bucha. Mariupol. Russia. Genocide

(transl. Yuliya Charnyshova)

I am writing this text listening to yet another air raid siren. First, I hear the siren blaring from my phone, via a specifically designed app that notifies Ukrainians of the alarms. Then a notification from a social media app—there is a Telegram channel which posts only information about air raids. And only after that, behind the glass of my window that is now covered with a cross made of adhesive tape to protect us from explosions, the actual city siren can be heard, and then several more of them. Under my window, I also hear a mother arguing with her adult son, complaining that he smokes too often outside without closing the door of their apartment.

Sometimes a car passes by. There is a loudspeaker on it that warns civilians of danger and asks them to take cover in air raid shelters. Once, before February 24, the same loudspeaker asked people to wear masks and maintain social distance. Sometimes at night you can see how some kind of military equipment passes by—long pipes of different thicknesses staring at the sky, preparing to fly. After the curfew, which starts at 10 p.m., there is almost no one on the street, but in fact you can go out. You just have to be extremely careful. Drunk people who get caught at night by police are handed call-up papers that require them to show up for military service.

Nonetheless, sometimes you look out the window at 3 a.m. and see a person, or two, or a small family walking. With their bags, pet carriers, they come from the side of the train station and have their children with them.

... Sirens from war films or sirens as if there’s an alien invasion. A mother and a child coming back from their walk, now rushing to the nearest shelter. Air raid alerts going off in almost every region of Ukraine. This means that somewhere someone’s home is being bombed right now. That someone shoots and reloads their weapon.

But I don't go to the shelter. And this is recklessness. An indiscretion. A habit of practice. And a privilege. It's horrible, but there’s a monstrously big difference: to live in a city under occupation, under siege, or under shelling—and to live in a city where there is none of this. Rocket attacks hit my city, Lviv, located in the west of Ukraine, only twice, damaging strategic infrastructure. But in the Lviv region, rockets hit a security center, killing 35 soldiers and wounding another 134.

And some cities no longer exist—they’ve razed them to the ground, in their failed attempts to capture a single large city. Except for Kherson, where pro-Ukrainian anti-occupation rallies are now being held and where journalists, officials, and activists disappear. They are probably being tortured and persuaded to cooperate with the occupying forces.

Almost every day, a few air alarms are being ignored. It's like masks during the pandemic. Over time, people treated them carelessly, despite being engulfed by COVID waves.

There is a huge sense of guilt felt by those who are safe, who have left their homes—they feel guilty towards those who are forced or decided to remain in the war zone or under the occupation of Russian and pro-Russian forces. Many people refuse to leave when they are forcibly "evacuated" by Russian soldiers. Only in rare cases these soldiers try to “rescue” you (and extract you to Russia to become part of propaganda stories for federal television channels) and not to rape or shoot you, or they force you to fight for Russia as cannon fodder in occupied territories…

Last week, I recorded a conversation with a woman from Mariupol who had lived in the city besieged by the Russians for about two weeks—no communication, no gas, no heating for anyone, no water and food for most people. Living in a shelter while the house above you is being annihilated. She had no idea that the same thing was happening to the whole city, and not just to them, who had taken refuge in the suburbs, near the Ukrainian military positions. As if the invaders were burrowing into the shelters with their claws-bombs, trying to obliterate them by piercing the ground. "It's like an irrational force trying to kill you, but you don't understand why. You don't understand the meaning behind their actions," she said.

On the 20th day of the war, they were pulled out of the shelter by Russian or pro-Russian forces and forcibly sent to Russia, to so-called "filtration camps", where Ukrainian refugees are used for Russian propaganda purposes. Everyone greatly underestimates the Kremlin propaganda machine. Instead of being an informative media outlet, it is just another weapon, reminiscent of the "Radio of the Thousand Hills" (Radio Télévision Libre des Mille Collines).

The Russian President believes that we as a nation do not exist. Russian troops consider me a Nazi. And for this, I and all other Ukrainians whom they call Nazis must be killed. And that’s what they are doing, they’re killing us.

I have the feeling that the world does not understand Russia when it tries to analyze it. But the world doesn't have to. Most importantly, the Russians themselves do not understand what country they live in. Most of them either believe or silently agree with the TV. If you haven’t seen footage from Bucha yet, then check it out. 40th day of the war. Those bodies have been there for weeks. But the majority of Russians believe what they get to see and thus silently agree with what is happening. Even if they don’t support the tyrannical power, they don’t interfere with it. They’re intimidated and yet compliant. Behind this complicity, some sort of responsibility lurks in joyless anticipation – gloomily watching over one's children – just like a ghost of oneself.

It is very scary, hard, and unbearable to spend so much time in the war mindset. And I'm talking nonsense now when I’m complaining, since I'm relatively safe. But non-humans are killing my people... You look at a woman on the street, and it hurts, as you cannot but remember the footage from the Kiev suburbs: what they did to people, how they left them on the curb afterwards. Or the recordings from video surveillance cameras: Russian soldiers, having left the Kiev region, lining up in Belarus to send home all kinds of stolen goods, like TVs, blenders, jewelry, and so on. This is the culture of that army.

I realize that this is a dehumanization of the enemy. We are all Homo sapiens, that is, people. But in order to live in a society with rules and enjoy its benefits you have to be a Human, not a murderer from the times that Hobbes described in Leviathan, when life was “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short".

(“... and which is worst of all, continual fear, and danger of violent death”)

This is not the sort of discourse that I wanted or chose, but just like many other Ukranians, I have to live in it. Fight and at the same time try to live a life in safer regions.

We call what is happening genocide. You can also call it sociocide. There istorture, rape, execution, war crime, looting, kidnapping, impunity, greed, cruelty, and sadism. Most of them do not understand what they are doing here and why they are so hated for their invasion. And they do not behave like humans who live in a free and safe society. Their sin is transcendental violence.

***

It feels like an undeserved gift, an accident, a privilege. To live in a city, in your own house, to have a job, to go for a walk or out for coffee. I'm embarrassed. But we are starting to understand that you can’t change anything through feelings of guilt, and you can and should put all of your strength into the economy, into volunteering, into territorial defense, into taking care of yourself. Into the help for internally displaced people. Into the help for abandoned animals.

My wife and I have decided to adopt a cat, which is being brought to us from Kharkiv—it was abandoned by its previous owner.

The war will not end soon. There are weeks and months ahead that will shock us even more than Bucha… More than 10 million Ukrainians have left their homes. Out of these, 6 million are now internally displaced persons. Another 4 million went abroad. Most of them are women, children, and elderly people. I know for a fact that Russia will continue to kill innocent people while I sit here and mourn for them.

Another air raid alarm ends. My wife enters the kitchen (where I am writing) from the most secure room in our apartment, the one with load-bearing walls. We understand that the danger has passed, which means that either the air defense has done a good job or that horrible things have happened to someone else. There are no safe places in Ukraine. But then there are places that were turned into hell on earth, where no one, least of all the sadistic and corrupt Russian leadership, would want to live.

Украина. Война. Буча. Мариуполь. Россия. Геноцид

Я пишу этот текст под сирену очередной воздушной тревоги. Сначала сирена исходит из телефона, через отдельно установленное приложение, оповещающее о тревоге. Потом приходит сообщение из телеграм-канала, который постит только оповещения о тревоге. И только после этого за стеклом, крест-накрест переклеенным скотчем, раздается одна, и тут же еще несколько завывающих сирен. Под окном слышу, как мама ругается с взрослым сыном, что он слишком часто курит, не закрывая дверь.

Иногда мимо проезжает автомобиль, который из динамиков предупреждает об опасности и просит пройти в укрытие. Когда-то, до 24 февраля, он просил из этих же динамиков носить маски и соблюдать дистанцию. Иногда ночью можно увидеть, как проезжает какая-то техника — длинные трубы разной толщины, уставившиеся в небо, готовящиеся к полету. После начала комендантского часа в 22 вечера почти никого нет на улице, но выйти можно. Если только очень аккуратно. Пьяным, которых поймали ночью, вручают повестки из военкоматов.

Но иногда смотришь в 3 ночи в окно и видишь, как идет человек, или два, или семья небольшая: с сумками, переносками, со стороны вокзала, с детьми.

… Сирены из кинофильмов про войну или как нашествие пришельцев. Мама с ребенком спешат с прогулки в ближайшее укрытие. Воздушная тревога на большей части территории Украины. Это значит, что где-то кого-то бомбят. Что кто-то стреляет и перезаряжает оружие.

Но я не иду в укрытие. И это опрометчивость. Самонадеянность. Привычка практики. И привилегия. Это ужасно, но это чудовищно большая разница: быть в городе под оккупацией, в осаде, или под обстрелами — и быть в городе, где нет ничего из этого. В мой город, Львов, находящийся на западе Украины, ракеты прилетали только дважды, в инфраструктуру. Но в области ракета упала на полигон и убила 35 солдат, ранив еще 134.

А некоторых городов уже больше нет — они сровняли их с землей, не захватив ни одного крупного города. Кроме Херсона, в котором проукраинские митинги и пропадают журналисты, чиновники и активисты. Их наверняка пытают и склоняют сотрудничать с оккупацией.

Почти каждый день несколько игнорируемых тревог. Это как с масками, когда был коронавирус. Со временем люди носили ее спустя рукава, хотя все тогда жили между волнами.

Есть огромное чувство вины тех, кто в безопасности, кто уехал — перед теми, кто вынужден или решил оставаться в зоне боевых действий или под оккупацией российских и пророссийских сил. Многие люди отказываются уезжать, когда их принудительно "эвакуируют" российские солдаты. Тот редкий случай, когда они пытаются вас силой "спасти" в Россию, используя вас в пропагандистских сюжетах для федерального телевидения, а не изнасиловать или пристрелить. А еще могут отправить воевать за Россию как пушечное мясо со стороны оккупированных территорий…

На прошлой неделе я записал разговор с женщиной из Мариуполя, которая около двух недель жила в осажденном россиянами городе — без связи, без тепла, многие без воды и еды, живя в укрытии, пока дом над тобой разносят и после того, как его разрушили. Она понятия не имела, что то же самое происходит со всем городом, а не только с ними, укрывшимися в предместье, возле дислоцирования украинской военных. Как будто оккупанты зарываются когтистыми бомбами в само убежище, пытаясь и его сровнять с землей, прорубив в земле воронку. "Как будто иррациональная сила пытается убить тебя, но ты не понимаешь, зачем ей это. Не понимаешь их смысла", говорит она.

И вот на 20-ый день их из убежища вытаскивают российские или пророссийские силы и принудительно отправляют в Россию, в так называемые "фильтрационные лагеря" для беженцев из Украины. И снимают там с ними пропагандистские видео. Все очень сильно недооценили кремлевскую пропаганду. Это не СМИ. Это "Радио тысячи холмов" — Radio Télévision Libre des Mille Collines.

Российский президент считает, что нас как нации не существует. Меня вот российские войска считают нацистом. И за это меня и всех остальных украинцев, которых они назовут нацистами, надо убить. Чем они и занимаются.

У меня чувство, что мир во многих смыслах не понимает Россию, когда пытается ее анализировать. Но мир и не должен. Самое важное в этой мысли то, что сами россияне не понимают, в какой стране они живут. Большинство либо верит, либо молча соглашается с телевизором. Если вы не видели кадров из Бучи, то ознакомьтесь. 40-ый день войны. Эти тела лежат там уже недели. Но большинство россиян верит или хотя бы молча соглашается с тем, что происходит, и если не поддерживает, то не препятствует тиранической власти, что становится запуганным, но соучастием, за которым в грустном ожидании молча смотрит на твоих детей твоя ответственность — твой призрак, подсматривающий за детьми.

Очень страшно, сложно и невозможно больно столько времени находится в майндсете войны. И я говорю глупость, жалуясь, так как я в относительной безопасности. Но там нелюди убивают моих людей… Смотришь на женщину на улице, и больно, вспоминая кадры из киевских пригородов, что они с ними сделали, оставив на обочине. Или видео с камер наблюдения: российские солдаты, выйдя из киевской области, в Беларуси выстраиваются в очередь, чтобы прислать домой украденные телевизоры, блендеры, украшения и так далее. Вот такая вот культура у этой армии.

Я знаю, что это дегуманизация врага. Все мы homo sapines, то есть люди. Но, пожалуйста, если ты хочешь жить в обществе с правилами и пользоваться его благами, то надо быть Человеком, а не убийцей из времен, которые описывал Гоббс в “Левиафане”, когда жизнь человека была «одинокой, бедной, неприятной, жестокой и короткой».

(... and which is worst of all, continual fear, and danger of violent death; and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short)

Это не тот дискурс, который я хотел, который я выбирал, но мне, как и моим согражданам, приходится жить в нем: воевать и в то же время пытаться жить жизнью в тех регионах, где безопасней. Мы называем это геноцидом. Можно также назвать это социоцидом. Это пытки, изнасилования, казни, военные преступления, мародерство, похищения, безнаказанность, жажда обогатиться, жестокость, садизм, похоть. Они не понимают, что они здесь делают и почему их так ненавидят из-за вторжения. И не ведут себя как люди, которые живут в свободном и безопасном обществе. Их грех — это запредельное насилие.

***

Это ощущается как незаслуженный дар, случайность, привилегия. Жить в городе в своем доме, иметь работу, гулять, выходить за кофе. Мне очень стыдно. И в то же время в социальных сетях начало появляться много разговоров, что да, все так, все ужасно, это несправедливость. Но ощущением вины ничего не изменишь, а свои силы можно и нужно направлять в экономику, в волонтерство, в территориальную оборону, в заботу о себе. В помощь вынужденным переселенцам. В помощь брошенным животным.

Мы с женой как раз берем кошку, которую нам везут из Харькова — ее бросила предыдущая хозяйка. Война не закончится так скоро, нас ждут недели и месяцы, которые будут потрясать больше, чем Буча… Больше 10 миллионов украинцев покинули свои дома. Из них 6 миллионов — переселенцы внутри страны. Еще 4 миллиона уехали за границу. Преимущественно это многодетные семьи, женщины, пожилые люди, дети.

24 февраля Россия атаковала с севера через Беларусь, с востока и с юга, через Крым. Между Крымом и востоком зажат Мариуполь. Западные области и часть центральных в относительной безопасности. Здесь есть понимание, что Россия собирается убивать еще многих моих сограждан, пока я тут сижу и плачу из-за всех погибших.

Заканчивается очередная воздушная тревога. Моя жена входит из самой безопасной комнаты в нашей квартире, с несущими стенами. Мы понимаем, что то, что нас пронесло, значит либо хорошую работу ПВО, либо то, что досталось кому-то другому. В Украине нет безопасных точек. Но есть места, куда Россия притянула с собой ад, в котором никто, особенно сама Россия и ее садистское, коррумпированное, мафиозное руководство (которое даже не в состоянии выполнить то, на что замахнулось), жить не хочет.

04 / 04 / 2022

speak to me in death’s language

there will still be time – and we’ll mourn them all, saying out loud their names. for now, it can still be dangerous. however, we're already running out of both words and tears left for the people, for the besieged cities, for the occupied settlements. not sure if he loves you? although all suggests that he does. or is it you who’s not sure? do you love him? oh, now it's all so irrelevant. I want to live, I want as many people as possible to survive, I want all of them dead so they can stop firing. in embarrassment, you choose what to say among the hastily learned words of another language muffled sounds fired by the artillery of the dark heart against my chest, like an echo in the crater of my pillow. shots that are audible from the windows blown out of the tower blocks burned to the ground. got to get married in time so they don’t deport you. cannot forget that I’m not allowed to post videos of the explosions online please, don’t forget – about Chernihiv or Mariupol. the long list of what got burned down everyone’s so tense, mad, yet cohesive in groups guilt, felt by those who now live in relative safety feeling guilty for those who are living in danger, having no heat, no gas, no communication, no electricity. some blame those who save themselves from death and for what? because death has come for us? because you speak to me in death’s language? and I was just lucky – to be born in some other city. I did not deserve this. they did not deserve what is happening to them. I, too, could be running on some beaten track, raising hands in front of the columns of Russian tanks, hoping that they would not shoot at us – like they did last time with that car with civilians in it. but why so? well, it's because there's war, going on the well-trodden path of crashed army vehicles “Russia wants to repeat it”. and they did repeat – after those who came to my land to kill and destroy. and they’ve done it before – they came here long ago, even before this war started. we’re forced to remember history. we know it so well because it is happening to us right now. so close in the distanced past – it’s right here right away and yet and still

(Translated by Yuliya Charnyshova)

смерть прийшла – і ти звертаєшся до мене її мовою

ще буде час – і ми їх всіх оплакуватимемо, називаючи імена. це все ще може загрожувати. хоча й зараз не вистачає ні слів, сліз: на людей на обложені міста на окуповані селища не певна, що він тебе любить? хоча все свідчить, що так. чи не певна, що сама його любиш? ох, зараз це все стало таким неважливим, хочеться жити, хочеться, аби вижило якнайбільше людей, щоб вони всі померли й перестали стріляти, розгублено обираєш що сказати з-поміж поспіхом вивчених слів іншої мови глухі удари артилерії чорного серця по грудях, ніби відлуння у воронці подушки, чутне з вибитих вікон згорілих дотла багатоповерхівок потрібно встигнути одружитися, щоб тебе не депортували не потрібно викладати вибухи у соцмережі не можна забувати про чернігів маріуполь довгий список пожеж.. всі такі знервовані, злі, згуртовані провину відчувають ті, хто у відносній безпеці перед тими, хто в небезпеці без тепла, без газу, без зв'язку, без електрики звинувачуючи тих, хто рятує себе від смерті у тому, що смерть по нас прийшла і ти звертаєшся до мене її мовою і мені просто пощастило, що я народився в іншому місті. я нічим цього не заслужив. вони нічим не заслужили того, що з ними відбувається. я теж міг тікати битим шляхом, здіймаючи руки перед колонами російських танків, сподіваючись, що не розстріляють, як ту автівку з цивільними. а чого так? та бо війна йде протореною стежкою розбитої техніки …і вони "повторили", але за тими, хто нею прийшов. і це вже не далеко не вперше сюди приходять. ми змушені пам'ятати історію. ми її знаємо, бо відбувається з нами тепер так близько у далекому минулому – просто тут зараз і досі

b

clustered | unclusteredAnyuta Wiazemsky Snauwaert

09 / 05 / 2022

Ik volg Roman Yuchnovets Telegram. Hij woont in Kyev, elke dag maakt hij een vijftigtal porties warm eten voor treinbestuurders, af en toe brengt hij eten en medicijnen tot bij mensen thuis in de dorpen rond Kyev.

Dagelijks publiceert hij zijn dagboek. Elke dagbeschrijving eindigt met «Минус ещё один день войны, а значит, мы на день ближе к победе.» «Weer een dag oorlog minder, dat betekent weer een dag dichter bij de overwinning.»

Gisteren las ik een tekst van journalist Maxim Trudolyubov. Hij schrijft over het begrip van de schaduw van de toekomst. Dichters hebben dit beeld al vaker gebruikt: er is een berg achter de horizon. Men ziet de berg nog niet maar wel zijn schaduw.

De mens heeft het vermogen om te anticiperen op wat de toekomst brengt, maar doet er niet altijd iets mee.

“The shadow of the future is a basic game theory concept; essentially it expresses the idea that we behave differently when we expect to interact with someone repeatedly over time (and hence expect to be able to punish and be punished for misbehavior).”

In de afgelopen dagen heb ik de laatste twee afleveringen van de podcast “Geschiedenis voor herbeginners” beluisterd. De voorlaatste gaat over Palestina. De laatste over de geschiedenis van Oekraïne.

Ooit was vandaag zo’n schaduw, een mogelijke toekomst. Als ik mijn ogen sluit en me concentreer dan kan ik tijdreizen, maar enkel naar het verleden. Ik kan me heel levendig, scherp, realistisch verplaatsen in mijn vroegere zelf, in momenten die heel echt aanvoelen. Ik voel mijn vroegere lichaam, denk dezelfde gedachten, ervaar dezelfde emoties. Soms zijn het flashbacks naar traumatische gebeurtenissen, die even intens aanvoelen als toen ik ze voor het eerste beleefde. Het is alsof mijn brein zaken kan opslaan die ik later gewoon terug kan heropenen. Ik probeer dit tijdreizen om te draaien. Ik wil de toekomst zien, voelen. Als ik nu een schaduw ben van mezelf, wie zal ik zijn en wat zal de wereld rondom me zijn?

«Минус ещё один день войны, а значит, мы на день ближе к победе.»

Wat een overwinning is kan niet objectief beschreven worden, ze is niet kwantificeerbaar. In een postwaarheidtijdperk kan alles gerelativeerd worden. Wat zal de overwinning zijn voor Oekraïne als Rusland zijn verlies evengoed een overwinning zal noemen?

Hoewel, dat doet er niet toe. Er zal geen Rusland meer zijn in de toekomst, enkel aparte onafhankelijke staten. Dat zie ik heel helder. Maar niet enkel Rusland zal vallen. Deze oorlog is het gevolg van globale processen en dynamieken: het koloniale denken van Rusland met het stille akkoord van de machthebbers in het Westen, het ideaal van mannelijkheid (grote ideeën en grote daden), sociale ongelijkheid, etc. Ik voel aan dat deze zaken inherent verbonden zijn en dat ze het paradigma waarin ik denk bepalen, maar ook dat er andere manieren van denken en doen zijn. Een radicale verandering van één basiselement binnen dit paradigma leidt noodzakelijkerwijs ook tot de verandering van de andere elementen. Dat is de schaduw die ik voel maar waarvan ik het silhouet niet zie, noch zie ik de berg zelf. Nog niet.

22 / 04 / 2022

Watch this first interview Ukrainian president Vladimir Zelensky gave to Russian journalists after the start of the war. It was March 27, 2022.

It is a historical document for so many reasons — but you decide on your own which one matters the most. I just want to pick this one quote and state that Ukraine is not only defending peace in Europe and the world. Ukraine presents a mirror today, which Europeans can look into and re-assess: which values were at the basis of the European Union? What role do they play today?

“Strategy is about what will happen to a country in a hundred years. I’m in no position to give advice to the Russians, but that’s what I call strategy. What will happen in five generations? Where will we be? I’m interested in what is going to happen to Ukraine, as a citizen, as a father. My children will live here.”

If your first reaction is to say “yes but he is a comedian”, “yeah but he says it this way until there are elections” or “yeah but he has a hidden economic agenda”, I suggest you think about these things: why is your reaction to distrust? Where is hope? What is the point of living in a world where you presume the other always has a hidden agenda?

15 / 04 / 2022

“No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main. If a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less, as well as if a promontory were, as well as if a manor of thy friend's or of thine own were: any man's death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind, and therefore never send to know for whom the bells tolls; it tolls for thee.”

— John Donne, “No man is an island”

Het geheel is meer dan de som der delen. En eigenlijk zijn deze delen ook gehelen, zij zijn op hun beurt sommen van andere delen. Het concept fractaal lijkt me erg toepasselijk op het organische en sociale leven.

— interpersoonlijk —

De opvoeding die ik van mijn ouders gekregen heb, is een herhaling van de opvoeding die ze van hun ouders hebben gekregen. Dat was een generatie die de Tweede Wereldoorlog had meegemaakt en geen liefde kon geven aan haar kinderen. Het trauma van mijn ouders is ook mijn trauma.

De opvoeding die ik van mijn ouders gekregen heb is een herhaling van miljoenen opvoedingen van mijn leeftijdsgenoten. Mijn trauma is een collectief trauma.

— binnenlands —

De relatie tussen mij en mijn ouders is dezelfde als die tussen de Russische staat en zijn bevolking. De relaties tussen en binnen gezinnen bevinden zich in hetzelfde sociale veld met dezelfde onuitgesproken basisregels (en die regels zijn de macht van het geld, de macht van het netwerk, de superioriteit van mannen ten opzichte van vrouwen, de superioriteit van Russen ten opzichte van de andere etniciteiten). Ons collectief trauma herhaalt zich in tijd en ruimte.

— buitenlands —

De relatie tussen Rusland en andere staten is een herhaling van de relaties tussen de groepen binnen de maatschappij, is een herhaling van de relaties binnen gezinnen.

Ik beeld me in dat ikzelf een punt ben in een fractaal: ik verhoud me tot oneindig veel andere punten.

Als je op mij inzoomt, merk je dat ik oneindig veel herhalingen ben van de wereld waarin ik zelf slechts een punt ben: van de herinneringen die ik heb, de boeken die ik heb gelezen, de films die ik heb gezien, de gesprekken die ik heb gehad, de vrienden die ik heb gekend, …

Als je op mij uitzoomt, verdwijn ik maar zie je de groepen waar ik deel van uitmaak: kunstenaars, vrouwen, 32-jarigen, emigranten, curatoren, juristen, mensen die last hebben van imposter syndrome, reizigers, mensen met trauma, mensen die in liefde willen geloven, …

Een fractaal stopt uiteraard niet aan de landsgrenzen van Rusland. Ik durf denken dat landsgrenzen er helemaal niet toe doen.

Het is niet zo dat je hier niets mee te maken hebt of niets kan doen. Jij, ik, zij — wij zijn allemaal één, wij zijn verbonden, al is het niet zo zichtbaar.

De ideologie achter deze oorlog is het primaat van Rusland over X*. Het is een lang gecultiveerd idee dat ook diep geworteld is in het Westen. Naar mijn mening is het zo dat iedereen die deze ideologie internaliseert, bijdraagt aan het wereldparadigma waarin we samen zitten.

* In Rusland uit zich dat als ‘Rusland über alles’, in het Westen als het onverschillig aanvaarden van de Russische hegemonie in de post-Sovjetregio.

Jij, — ja, jij — speelt er ook een rol in. Dat doe je wanneer je bijvoorbeeld over de Sovjet-Unie spreekt en ‘Rusland’ zegt. De Sovjet-Unie omvatte de volgende republieken: de Russische SFSR, de Oekraïense SSR, de Wit-Russische SSR, de Oezbeekse SSR, de Kazachse SSR, de Georgische SSR, de Azerbeidzjaanse SSR, de Litouwse SSR, de Moldavische SSR, de Letse SSR, de Kirgizische SSR, de Tadzjiekse SSR, de Armeense SSR, de Turkmeense SSR, de Estse SSR.

Jij — hoe ver van het oorlogsgebied dan ook — kan iets doen. Care. Zorg voor anderen, zorg voor iemand die je niet kent, zelfs als je denkt dat je je dat niet kan veroorloven. Lees het boek Het Achtste Leven van Nino Haratashvili. Stop met denken dat je niets bepaalt. Verdiep je en wees bewust. Als iedereen vanuit haar of zijn plaats in de denkbeeldige fractaal zorgt, zich verdiept, bewust handelt, dan zal dit fractaal er ook anders uitzien.

08 / 04 / 2022

Op 3 april werden er beelden gepubliceerd van dorpen en steden vlakbij Kyev die het Russische leger verlaten had. Het Russische leger heeft honderden onschuldige mensen vermoord en verkracht. Lijken werden met tanks overreden. Geen enkele dood mag vergeten worden. Alle personen die betrokken zijn bij deze misdaden moeten gevonden en eerlijk berecht worden. Iedereen, en dat wil zeggen: wie beslissingen nam, wie beslissingen uitvoerde, wie hielp, alsook iedere actor in de propagandamachine. Vroeger was ik soms onverschillig — zo bijvoorbeeld tijdens de oorlog in Syrië —, wel, dat had ik — ongeacht welke redenering of persoonlijke situatie dan ook — niet moeten zijn. Vroeger was ik een apolitiek persoon, dacht ik soms, welnu, dat was verkeerd gedacht.

“Are there languages with no first person?” “Vietnamese comes pretty close. Pronouns in conversation are almost all words for family members. The pronoun used depends on relative age. Speaking to a slightly older woman, for example, I would call myself em (little brother) and she would also call me em; she would call herself chị (big sister) and I would call her chị. So in a typical conversation there is no surface representation of person at all. There is no inflection so no question of verb agreement. I have even been in the situation of me and a Vietnamese speaker both calling each other and ourselves anh (big brother) when the age difference was not yet established. The English translators of the highly amusing novel Dumb Luck by Vũ Trọng Phụng try to get the effect of this across by having characters speak to their family members using third person kinship terms instead of personal pronouns. I’m not sure whether it seems like that to Vietnamese speakers.”

Vroeger vroeg ik me oprecht af hoe de tijdgenoten van nazi’s zich voelden., Wat bezielde deze mensen dat ze het uitmoorden van Joden hadden toegestaan, dat ze Joden verklikten. Vandaag vervalt deze vraag.

Hoe komt het dat wie nu in Brussel komt protesteren tegen de oorlog een keuze moet maken tussen vreedzame oproepen en oproepen om meer wapens te sturen naar Oekraïne? Hoe komt het dat “er zijn altijd ergens gruweldaden in de wereld en ze zijn nooit prettig” een reactie is op beelden van lijken van mensen die anderhalve maand geleden in een niet-gebombardeerde stad leefden? Hoe komt het dat je op het internet te lezen krijgt: “We moeten de beide kanten horen. In een oorlog liegen de beide partijen. Het is te vroeg om te oordelen” of “We steunen de oorlog niet maar zijn afhankelijk van olie en gas, we laten ons volk toch niet bevriezen”? Hoe kunnen vredesbesprekingen enerzijds en bombardementen, martelingen, verkrachtingen en moorden anderzijds in dezelfde ruimtetijd plaatsvinden? Hoe kunnen we aan de waarheid appelleren in een post-truth-tijdperk? “Het zijn zij, niet wij.” In onze lessen geschiedenis hebben we het niet over Oost-Europa gehad. Niet over Azië. We hebben het ook niet gehad over Afrika en het kolonialisme. We hebben geen les empathie gekregen.

De gruweldaden die nu — terwijl ik dit schrijf en u dit leest — in Oekraïne begaan worden, worden afgezwakt door historische vergelijkingen met nazi-Duitsland, Agent Orange, Sovjetmisdaden … Ofwel spreek je over de gruweldaad en word je verlamd, ofwel hanteer je een beschouwende metataal en op dat niveau is de urgentie niet even voelbaar. Ik had graag gehad dat ik het kon: de dwingende urgentie laten resoneren in elke zin waarmee deze oorlog beschreven wordt. Elke gepleegde moord is een onverdraaglijke concentratie van gruwel in ruimtetijd én tegelijk situeert ze zich tussen verleden en onvervulde toekomst. Elke vermoorde heeft iets gevoeld, gezegd, gedaan voor zijn of haar einde. Elke vermoorde is een deel geweest van een gemeenschap, van een staat, van de wereld. Proberen uitzoomen van die ene gruweldaad voelt erg fout en hypocriet aan; het lijkt een verschuiving van de aandacht. Ik was graag in staat geweest om alles met alles te verbinden en dat mee te nemen als zichtbare, hoorbare achtergrond van elke zin waarmee deze oorlog beschreven wordt. Hoe zou het zijn om zonder “ik” en “u” te zijn? “Ik” is het centrum. “U” is de periferie. Ik is beter en juist. Zelfs wanneer ik fout is, is het beter om het toch te redden want anders is het zelfbeeld in gevaar. Wat ik in haar/zijn rugzak heeft, is bepalend voor haar/zijn perspectief en relatie tot anderen. Ik ligt aan de basis van de natiestaat, van het kapitalisme als politiek-economisch stelsel, van competitie en van het uniek, beter, slimmer, sterker willen zijn. Hoe zou het zijn om de dichotomie van centrum en periferie te vergeten?

04 / 04 / 2022

21 maart 2022

Op 24 februari 2022 heeft het Russische leger onder bevel van de Russische president Vladimir Poetin de grens van Oekraïne overgestoken. Zo is de oorlog begonnen.

Als Russische staatsburger veroordeel ik deze aanval. Alle militaire acties moeten onmiddellijk gestopt worden en de oorlogscriminelen moeten volgens de internationale wetgeving vervolgd worden. Op dit moment betaalt Oekraïne de bloederige prijs voor de vrede in Europa en heel de wereld.

Het is voor mij onmogelijk om een zinvol leven te leiden zonder me ervan bewust te zijn dat er op dit moment een oorlog gevoerd wordt, in mijn naam. Ik ben geen redenaar of politicoloog en ik zou geen goede vechter zijn. Het beste wat ik kan doen in de huidige omstandigheden, is communiceren, mensen bereiken, anderen bewust maken.

De oorlog is op 24 februari 2022 begonnen maar eigenlijk is hij al langer bezig. Wat veranderd is, is de schaal van de actie, de propaganda, de confrontatie. Maar de aanleiding, die ligt al veel verder terug. Ik wil vertellen hoe ik die ontwikkelingen gezien en ervaren heb.

8,5 jaar geleden ben ik naar België verhuisd. Daarvoor heb ik een half jaar in Nederland gewoond en nog een half jaar in Thailand. Zolang ik me herinner, wou ik ontsnappen uit Rusland. Toen ik op school zat, begon er een deconstructie van het onderwijs: in plaats van examens als evaluatie aan het einde van het schooljaar werden er testen ingevoerd. Enkel met multiple choice werd er gewerkt, en dat bij alle vakken. Dat betekende een heroriëntatie van de taak van het onderwijs: in plaats van kennisverwerving als doel, moesten kinderen leren tests correct invullen. Het verschil met een gemengde evaluatie (examens, tests en andere vormen) lijkt misschien subtiel maar in the long run draait zo’n systeem uit op een simulatie van het onderwijs: de inhoud wordt compleet uitgehold.

Geschiedenislessen zijn de lessen waar je bewustzijn als mens binnen de context van een natiestaat gevormd wordt, toch? Wel, de lessen begonnen met de Kyev-periode, daarna werd Moskou gesticht, vervolgens was er veel aandacht voor Rurik- en Romanov-dynastieën. De Eerste en Tweede Wereldoorlog werden met elkaar in verband gebracht. Wat tussen de jaren 1950 en nu gebeurd was, handelden we in 1 à 2 lessen af. Als ik een tiener was, zegden de namen Andropov, Chernenko, Brezhnev en Khrushchev me wel iets, maar wie wie opvolgde en wie wat deed, dat wist ik helemaal niet. Ik denk niet dat we het woord ‘holocaust’ op school ooit te horen kregen. Zeker tot mijn twintigste zat ik met het vooroordeel dat Duitsers slechte, gevaarlijke mensen waren. Enkel de romans van Erich Maria Remarque hebben mij doen beseffen dat dat niet zo was. Toen pas kwam ik met een shock tot het besef dat ik zo veroordelend over zo veel mensen dacht zonder er ooit maar één van ontmoet te hebben.

Dan ben ik rechten gaan studeren. Ik wou procureur worden en rechtvaardigheid brengen door misdaden te onderzoeken en door ‘slechteriken’ op te pakken. Tegelijk dacht ik dat ik met een rechtendiploma heel makkelijk uit het land zou kunnen emigreren. Mijn toenmalig lief studeerde aan dezelfde rechtenacademie (de beste juridische onderwijsinstelling op post-Sovjetterrein werd gezegd). Op een dag, vertelde hij, hadden ze een seminarie over corruptie. De vraag was of je als toekomstige procureur geld zou aannemen als jou dat in een zaak aangeboden werd. Iedereen zou uiteindelijk akkoord zijn gegaan. Zo werkt het nu eenmaal, zo bleek. En het is niet aangeraden om tegen de stroming in te gaan.

Zelf was ik nog niet met corruptie geconfronteerd. Dat gebeurde pas een 7-tal jaar later. Ik deed stage en vrijwilligerswerk bij CKP (The Investigative Committee of the Russian Federation), het staatsorgaan dat instaat voor de bestrijding van corruptie. Het werk was erg zwaar en triest maar alles voor de goede zaak, denk je dan. Maar gaandeweg zag en hoorde ik dingen die niet klopten. Een rechercheur die ontslagen werd omdat ze een politieagent voor corruptie wou vervolgen. Rechtszaken over laster en eerroof aan het adres van politieagenten als er te weinig misdadigers aan het einde van de maand gepakt werden.

Kortom, corruptie was omnipresent. Ik zag dat het slechts in theorie mogelijk was om zelf oprecht te werk te gaan. Je kan gewoonweg niet tegen de stroming in gaan, want Wie ben jij? Denk je dat jij beter bent?

Uiteindelijk studeerde ik met grote onderscheiding af aan de rechtenacademie en begon ik met een doctoraat. Ik walgde van onmacht en onrecht, van het verschil tussen wat er in onze wetten geschreven staat en wat er in werkelijkheid gebeurt. Ik stopte dan ook met mijn vrijwilligerswerk bij de procureur. Maar tijdens mijn doctoraat werd ik zelf een actor in het systeem van corruptie en bedrog. Ik moest betalen voor de verplichte reviews van mijn dissertatie. Officieel gaat dat allemaal gratis uiteraard. Maar in de praktijk is het de gewone gang van zaken. De doctores en professoren die een dergelijk verslag moeten schrijven hebben een belachelijk laag loon en moeten het eigenlijk in hun vrije tijd schrijven – dan is het toch maar logisch dat doctoraatsstudenten uiteindelijk geld moeten ophoesten, niet?

Maar de verdediging ging mis. Ik had één stem te weinig: drie jaar onderzoek en 1000 à 1500 euro waren voor niets geweest. 8,5 jaar geleden heb ik mezelf kunnen redden door in België te beginnen studeren. Ik wou weg van de corruptie, weg van het systeem waarin je kapotgemaakt wordt als je dwarsligt, weg van het spel waaraan je wel moet meedoen, zelfs als je het immoreel vindt. In de jaren die volgden zag ik dat de mechanismen die aan de basis liggen van een open samenleving (onderwijs, vrijheid van pers, mensenrechten, etc.) één voor één uitgeschakeld werden. Dat heeft – geloof ik – ook mensen veranderd. Het is geen oorlog van Poetin alleen. Het is een oorlog van alle gewetenloze mensen die meedraaien met het corrupte systeem, die zich niet meer kunnen inbeelden dat het leven ook anders kan.

c

clustered | unclusteredDaniil Galkin

09 / 05 / 2022

Shooting Stars

2014

Against the background of the second wave of decommunization in Ukraine, which continues to remove monuments, sculptures, mosaics and bas-reliefs (for example, a recent disassembly of sculptures under The Peoples' Friendship Arch), I propose to see the exhibition Stargapad, which is part of the long-term project Dismantling, which started in 2014.

About Shooting Stars

When comparing root crops with building foundations, the Soviet past for Ukraine is a kind of material for the root formation – a basic element of all modern structures. And the result of its physical ‘uprooting’ in the form accepted by the current government is that the memorials, architectural monuments and other cultural values are faced with the threat of destruction. So the dust will continue to rise into the air for a long time. And to settle down on Ukrainian windowsills, day in, day out.

Currently, the replacement of totalitarian symbols of the past with state symbols is ongoing in the country. That process emanates from the removal of the monument dedicated to Lenin near Bessarabska Square (Kyiv) committed on December 8, 2013, by ‘Svoboda’ party members. The ‘Shooting Stars’ clearly demonstrates this process, proposing to think how easily one thing can be substituted by another, or disguised as another thing. This process resembles the defence mechanism, used by some species of animals and plants when they are mimicking other animals' / plants' / surroundings' colour and shape. It is noteworthy that they disguise themselves not only for protection but for an attack as well.

There are numerous examples of the mimicry of state symbols throughout the country, one of which is located in Dnipro city: here, on the ceiling of the mall, there is a giant roof installation – a composition of the ‘Pravda’ newspaper logographic name and three coats of arms of the Soviet Union. The coats of arms were simply covered with stickers in Ukrainian flag colours a while back. This is a perfect example of how the retouching under the state ‘corporate’ style happens while both the form and its content remain the same.

Remarkably, the decommunization laws do not apply to museum work. However, on the pretext of ‘re-exposition’, a large number of exhibits are hidden in storages, and inscriptions engraved on the marble walls are covered by a drywall. But you cannot say the same about the street artefacts from the past, which are either destroyed during dismantling or sold for scrap.

Given this situation, I proposed to remove two festive/ideological light structures depicting Soviet stars from the facade of the former building of the Ministry of Ferrous Metallurgy in the centre of Dnipro and to transfer them to the museum after the exhibition.

In the end, I haven't managed to dismantle the structures for the current exhibition. But I look on the bright side: they still operate in public space. Nevertheless, the dialogue with the city authorities is ongoing.

The central symbol of the entire exposition is the object «Alpha and Omega», where the alpha is the five-pointed star, and the omega is the swastika. If we consider these two components as mirrors of one another, then we can see how the swastika turns into the last letter of the Latin alphabet (approx. 3 ). Thus it transmits from one era to another, through the symbol of the beginning and end of all things.

— From an interview with ArtUkraine: "Soviet luggage or 'Dismantling'?"

Metal structures, built in a "festive-ideological" style, draw a logo using "Ilyich's light bulbs". This allows us to consider the narrative of the totalitarian regime and the arrival of the new in the form of a “solar eclipse” or “mystical atheism. The Demounting program proposes to fix the internal problems of the system by analyzing triggers and understanding patterns, and not just by externally destroying the existing one”, says the artist.

— From an interview with Huxleў

22 / 04 / 2022

Selective breeding

20'49'', 2013

This video work shows the temporary intoxication of several common rats with opium, during which their tails are tied together. They awake as an already selectively crossed new organism that reorganizes previous social positions. Through this violent construction of a rat king, the work reflects on issues such as manipulation through the imposition of value systems, hoaxes, beliefs.

Rat kings are customarily formed through the birth of a new brood of baby rats in an unfavorable place. They can only survive when other rats bring them food. The work also recalls the “Universe 25” experiment (1965—1973), in which research psychologist John B. Calhoun created a 'rat paradise' in order to study the societal behaviour of a colony in particular circumstances and what it can tell us about civilization. Some of the rats, which consistently followed foreign objects, were labeled “pied pipers” – a reference to the story of The Pied Piper of Hamelin, where a rat-catcher, in retaliation for the city’s refusal to pay a reward for ridding the city of rats, used witchcraft to abduct the city's children, who then disappeared irrevocably.

In the present context, the work alludes to the process of “liberation” of the Ukrainian people from a supposedly fascist regime by the Russian Federation; the deportation of people against their will and the long-term destabilization of the world economy through the military operations in Ukraine.

No animal was harmed in the making of this work.

15 / 04 / 2022

Spring

0'57'', 2022

On April 11, the Azov Regiment reported the use of a poisonous substance of unknown origin by the Russian occupation forces against Ukrainian military and civilians - a chemical weapon whose colorless liquid at room temperature has a faint smell of apple blossoms. This is how spring came to Mariupol. For some reason, this is not particularly talked about in the news, perhaps in order not to spread panic. Therefore, weather forecasts, which inform us about the direction of the wind, have become of vital importance from now on.

* The video shows elements of the Uzhgorod Museum of Folk Architecture and Life.

08 / 04 / 2022

Untitled

1'11'', 2011

Realizing that at the moment in some Ukrainian villages and cities they are raping women and children, tying their hands and cynically shooting in the back of their heads, you recall a photograph from Bucha with an image of a dog that does not leave the dead body of its owner. Similarly, Ukraine has been waiting for 44 days for the awakening of world leaders, who are obviously not doing enough to stop this hell, the gates of which may subsequently swing open to the whole world.

#bucha #hostomel #mariupol #kharkiv #kyiv #chernihiv #melitopol #irpin #chernobyl #konotop #sumy #kherson #berdyansk #borodyanka

A dog next to the body of a murdered cyclist, April 3, 2022, Bucha, Ukraine. Photo: © SERGEI SUPINSKY / AFP via Getty Images

04 / 04 / 2022

Boys

5'09, 2016

To deconstruct the absurd statements of the Russian Federation against the Ukrainian people, unsuccessfully attempting to mislead the international community, I have used Joseph Beuys’ video Sonne statt Reagan (1982), replacing the audio track with Sabrina’s song Boys (1988). The audio and video are intentionally out of sync, the only match is the likeness of the word “boys” and the artist's name, Beuys. Thus, the doublespeak turns Beuys’ political song, conceived as a pop music work (to up the chances of inspiring larger audiences with his ideas), into a pop hit in which Joseph Beuys does not sing about the war, weapons and the peaceful skies but about himself, the sun and guys in a swimming pool. (artist’s statement from 2016)

d

clustered | unclusteredMasha Ivasenko

09 / 05 / 2022

Babushka

I love this word, babushka, it means granny. My granny, the mother of my father, lived in Ukraine for her entire life, in a little village next to Dnipro. Her name was Nadja. She died in 2014. I went to visit her a few times when I was a child and once when I was an adult, in 2009. That was the last time I saw her.

My uncle, my aunt and my cousins still live in a little town near the one where my grandmother used to live. Since the beginning of the war, my uncle has joined the army. I’m very worried about them and often write to my cousin, trying to find out if everyone is alive and well.

I’m trying to remember this land and babushka Nadja. She was big (although maybe I was just small), with a large round face and big hands, rough from work. She spoke a special mixture of Ukrainian and Russian (surzhik) and I didn’t always understand her.

Therefore, I was very shy to talk or ask her about anything. I remember when I was 9 years old and watched how my babushka was milking a cow. The air was very tight and fat, it smelled of manure and raw milk. I heard the sharp sound of a jet of milk hitting an iron bucket. I was amazed by this scene and I couldn’t move. “Would you like to taste the fresh milk from the cow?”, Babushka asked. I silently nodded my head. “Bring me a glass.” She milked the milk straight into a glass and gave it to me. The milk was very warm with a strong smell. I took a sip, got sick and threw up.

The smells and sounds of this village were special. Everything was very tight and loud. It was as if the air was smeared with sunflower oil. The pigs grunted so loud that I was afraid to come close to the pigsty. (Babushka had a quite large farm for a single woman; there were cows, pigs, geese, chickens and even doves). I remember she put me on the back carrier of her bicycle and we went to the market to sell milk. Iron cans of milk hung from the frame of the bicycle and sometimes painfully hit my legs as we rode along the village road. I didn’t complain because I was mesmerized by the sound of these cans which rang like bells.

It was summer. In my memories Ukraine is an eternal hot summer. But babushka’s clay house was always cool inside. The outside was painted white, the porch was covered with vine. In order not to heat up the house, babushka cooked in a special summer kitchen — a small separate house with a stove. Always very fatty food. I prefered to eat mulberries that grew in the yard instead.

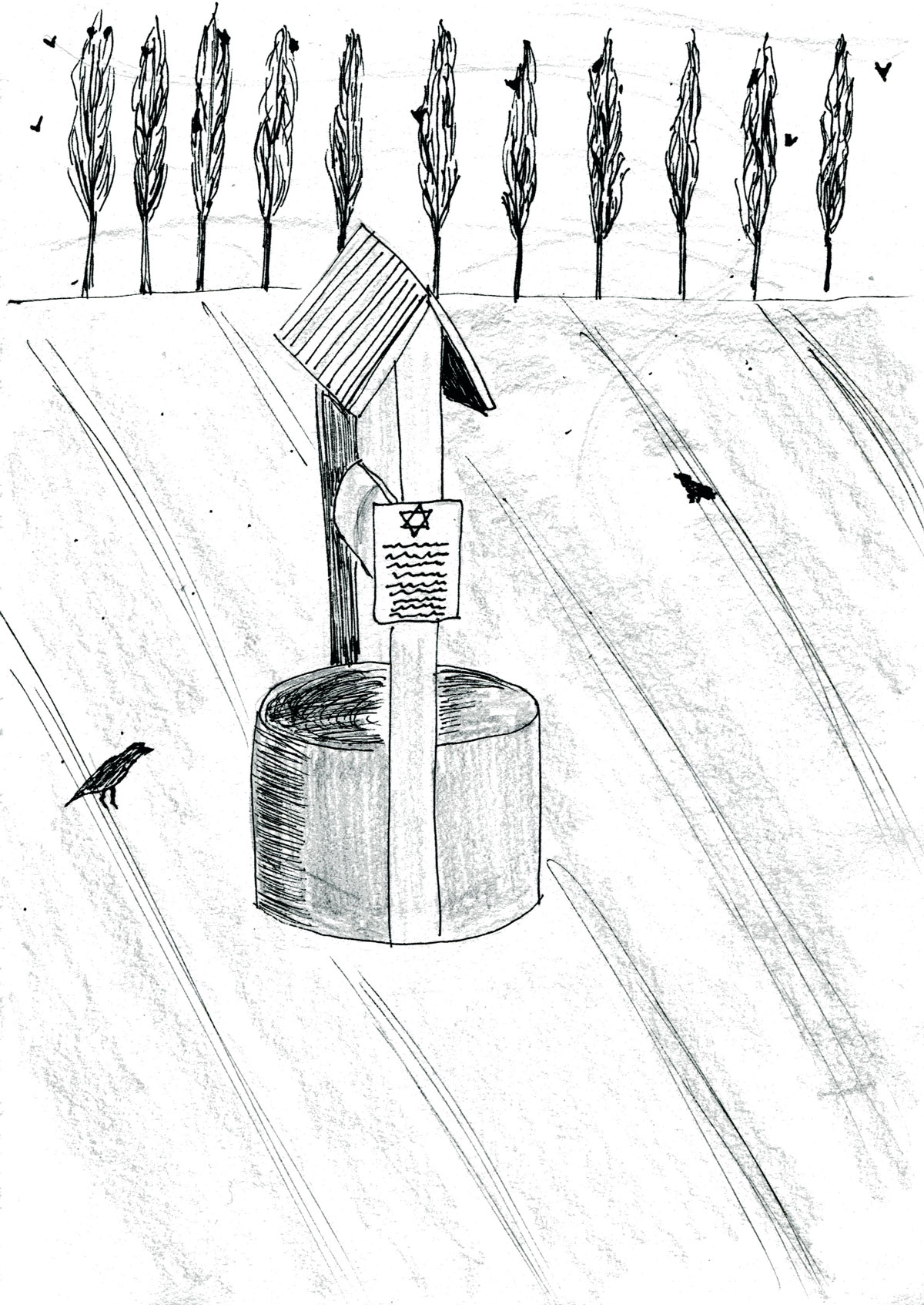

I visited babushka during winter once in 2009. She no longer had a large farm, only chickens and an old watchdog remained. And babushka herself seemed smaller. We spent quiet evenings: she was watching TV and I was reading a book. We didn’t really talk. I liked walking in the snowy field. It was enclosed by a slender line of poplar trees, which looked like long candles. There in the field I found a well with a commemorative plaque with a Star of David and Hebrew writings on it. I found out that Nazis executed Jews in this field during the Second World War, and that my babushka’s village was originally a Jewish settlement.

In 2014, babushka wanted to sell chickens at the market and asked my uncle (her youngest son) to take her there by car. She didn’t feel well and suffered a stroke in the car. She died. “Damn, why did she have to go to this damn market with these damn chickens”, my uncle lamented.

Recently, I caught myself on a strange thought. It’s a good thing that babushka didn’t live to see 2022. How would one explain to her that Russians are bombing the Ukrainians because they consider them fascists.

I’m sick. I take a pen and draw what I remember.

22 / 04 / 2022

What is wrong with Russia?

I saw this post from a Facebook friend two weeks ago and I keep thinking what exactly is “deeply, deeply wrong”. I don’t want to think about the Russian army, I can’t imagine how an army can be normal at all. I want to analyze what is wrong with the Russians, because there has been something wrong for a very long time.

I was born in Russia and lived there for 37 years. I remember feeling insecure in front of institutions since kindergarten. Violence and humiliation were inscribed in all education systems. This seems normal, since any educational institution is based on power and discipline. As Michel Foucault puts it in Discipline and Punish: “The power to punish is not essentially different from that of curing or educating”. But in Russia this power to punish and discipline goes beyond kindergardens, schools and hospitals. In any bureaucratic office connected with public service, you can be shouted at and humiliated. It is not surprising that for Russians this is an absolutely familiar state of affairs: we are all used to the fact that even conductors in public transport having special power over passengers are not particularly polite.

Two entities are always included in the mechanism of power: the one who has power and the one who must obey. If there is no subordinate, there is no power. Both positions are characterized by fear: fear of who is in power and fear of losing power. At all levels, Russian society seems riddled with this fear.

The other side of this fear is to avoid responsibility. As paradoxical as it may sound, it seems to me that responsibility is something opposite to the totality of power. To respond to something is, among other things, to admit a mistake. However, whoever has power cannot make or at least admit mistakes. In August 2000 (it was the very beginning of Putin’s presidency), a disaster occured in Russia: the Kursk nuclear submarine sank and all the sailors died. Putin not only didn’t immediately announce the tragedy, but also didn’t allow foreign aid (supposedly for reasons of state security). Only 10 days later, the government officially recognized the death of the sailors. In September 2000, Putin gave an interview to Larry King. “What happened with the submarine?”, King asked. “It sank”, Putin replied. This phrase has become a symbol of Putin’s attitude to his own country.

Fear of responsibility, fear of making decisions - that’s what I constantly encountered in Russia. Consequently, in public space no one wants to take responsibility for incidents. For example, if on the street a person falls off a bike or a fight breaks out, none of the passers-by will offer help or call the police. At first I thought that Russians simply do not have a sense of empathy or don’t want to show this empathy in public spaces to strangers.

Once I fell under a train when I wanted to get in. The steps were slippery and the distance between the steps and the platform was large. So I fell onto the tracks with my backpack and fainted for a minute. I woke up from the words of the conductor: “Damn! If she dies, I’m responsible for it!” “I’m alive! Help me get up”, I said. He and some other passengers helped me enter the train. My head was bleeding and I asked the conductor for a first-aid kit to treat my wound. “We don’t have a first-aid kit! You are alive, so enjoy it!”, the conductor answered. He was very angry and scared at the same time.

At first, it looked like a complete lack of empathy. In retrospect, however, I understand the problem is much deeper: it lies in the total fear of taking responsibility. This fear is really all-encompassing, and that is why we have not been able to build a civil society in Russia for many years.

While Russian soldiers are killing civilians in Ukraine, most Russians believe that the “special operation” is very important and the government is doing the right thing. The number of dead Russian soldiers is carefully hidden from the media. Recently, the Russian warship “Moscow” sank in the Black Sea. Pro-government Russian media stated that “the entire crew had been evacuated”, but in fact they are still hiding information about the dead sailors.

Russia cannot take responsibility, neither for its murders nor for its own dead. But this war will be over. And I deeply, deeply hope that Russia will have to take responsibility for all the crimes it committed.

15 / 04 / 2022

About body and war

From the beginning of the war the main question of pro-Putinists to people opposed to the war has been: “Where have you been for eight years?” “Where was I eight years ago?”, I asked myself. Eight years ago I joined {rodina} (which means {motherland} in Russian), an artistic group making experimental political art, based in Saint Petersburg. Since 2013, this collective has been criticizing the Putin regime in performances. Here you can watch the annual performance report of {rodina} for 2013-2014.

In June 2014, I conducted the performance Time to redden:

Because of my infertility I suffered from reproductive pressure in Russia, which is a quintessentially patriarchal country. If you are married and have no children by the age of 28, it means something is wrong with you (not only doctors but also my grandmother and even colleagues at work constantly emphasized I needed to be treated in order to have children). The reproductive pressure is essentially a governmental, biopolitical pressure. At the time of the performance, the conflict in Donbas had already been going on for three months. “Why does Russia want me to give birth?” My radical conclusion was: to have more soldiers. But my body doesn’t owe anything to anyone.

Obviously, the connection between war and bodies is extremely direct: war destroys bodies, tears them to pieces, mutilates them.

In the meantime, it has been confirmed that not only Ukrainian women, but also children were raped by Russian soldiers. I shivered when I read a story about a Ukrainian girl who fled to Poland, where she found out that she was pregnant after being raped in Ukrain. As she already obtained refugee status in Poland — where abortion is banned — she cannot go back to Ukraine to end her pregnancy. Now, the war lives on inside her. War appropriates human bodies in order to acquire its own. A headless body, giving birth to death.

08 / 04 / 2022

“My language is imprisoned.”

Mutism and ways to overcome it in the Russian regime.

From the beginning of the war until March 5 protests were still possible in Russia (although people were massively arrested), there were also publications in independent media criticizing the war.

On March 4, however, the Russian government fast-tracked a law of “military censorship”. Literally this means that it is no longer possible to oppose the war because this “discredits the actions of the Russian army”. Equally, you are not allowed to publish any articles on the war, as they are automatically discredited as fake news . You can’t call the war a war, you should call it a “special operation”. Who fails to comply with this law, is liable to imprisonment up to 15 years. Consequently, some independent media stopped covering events in Ukraine, other media were blocked or moved abroad. Instagram and Facebook were blocked; Meta was even recognized as an extremist organization.

As the repressive bulldozer has frightened people, they stopped protesting en masse. My friends from Russia indicate that they are literally suffocating from the inability to speak the truth. On Facebook and in private messages I constantly read phrases such as “My words are in prison”, “my speech was canceled”, “I can’t speak and I can’t breathe normally”, and “ I no longer have a language”.

However, some individuals and anti-war communities began to actively invent forms of (decentralized) micro-protest, in addition to graffiti and stickers in urban space (which are, however, quickly painted over or torn off).

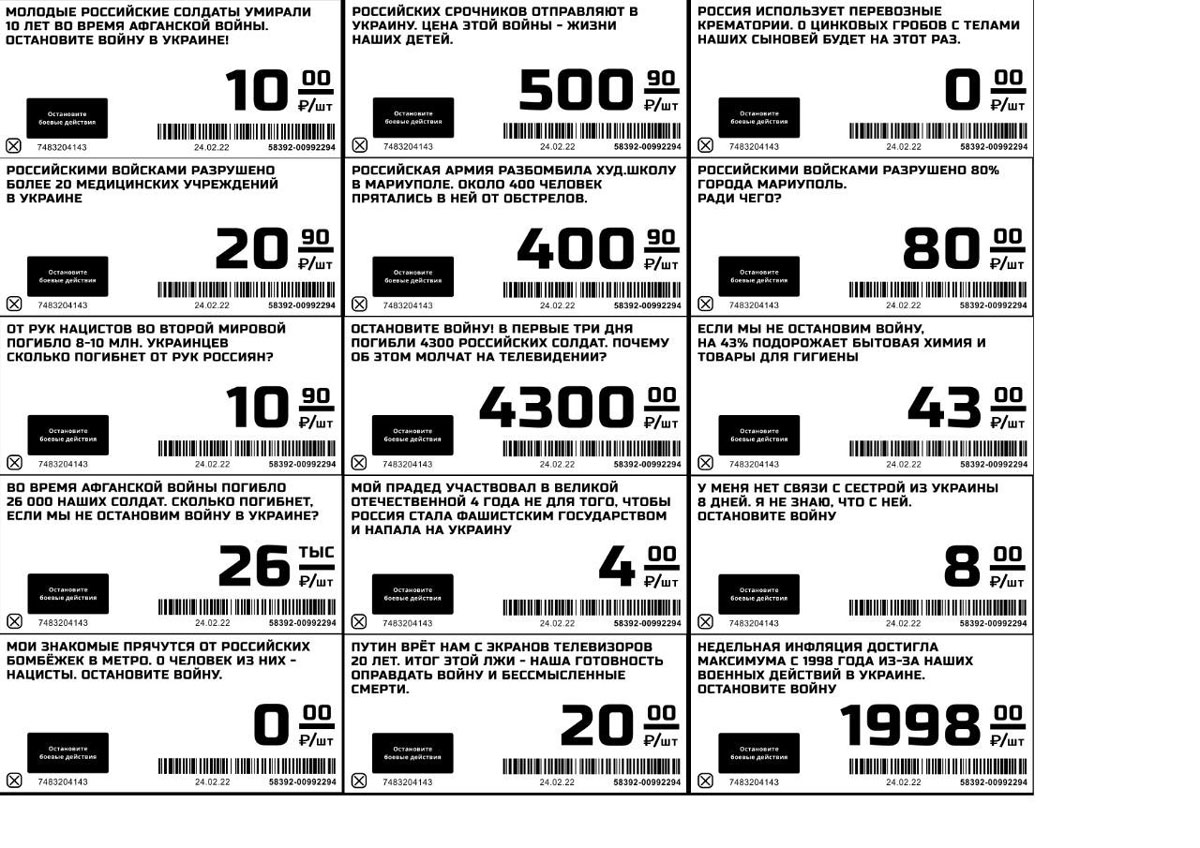

The most active protest group is “Feminist anti-war resistance”. In their Telegram channel they immediately began to propose alternative forms of opposition, such as crying in the subway or in public space, signing banknotes and coins with anti-war statements, printing and sticking “price tags” on products in stores. On these “price tags” written numbers are visible; next to them, instead of the name of the products, there are inscriptions such as “I’ve had no connection with my sister from Ukraine for 8 days, I don’t know how she’s doing, stop the war”, “Russian troops destroyed 80% of the city of Mariupol, what for?”

Mid-March, “Women in black”, an action by feminists in Russia, began. It turned out not to be safe. Some girls were arrested, although they stood in silence, dressed in black with white flowers (the white rose is a reference to a resistance group in Nazi Germany).

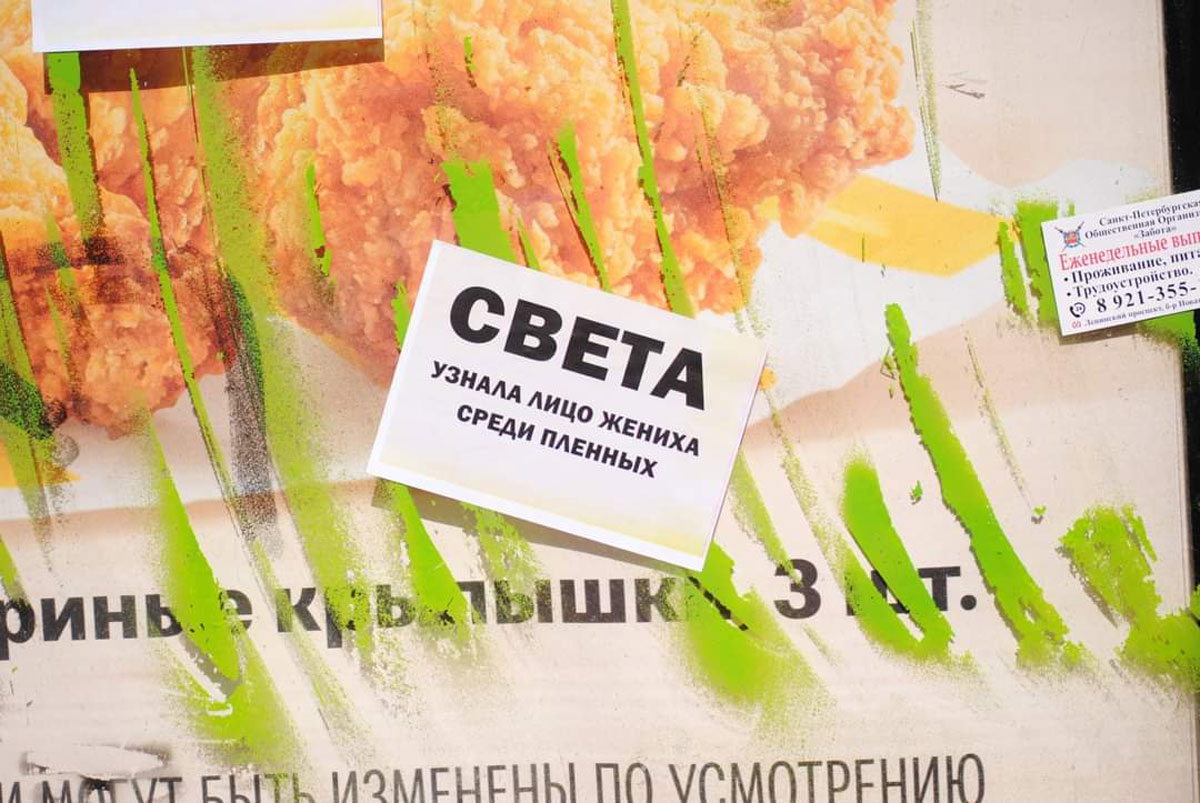

Another protest action is connected with a sensitive topic, illegal prostitution in Russia. In St. Petersburg bright stickers with women’s names and phone numbers are omnipresent at bus stops and on billboards.

The artists cyanide zloy, bobo art group and anush panina decided to tactically use this graphic style. They took the same bright stickers, wrote a woman’s name and anti-war statements on it, such as “VERONIKA can’t get through to her sister in Mariupol”, “ANGELA lost her sleep, her husband went missing”, “SVETA recognized her groom’s face among the captives”.

By the end of March, evidence from Mariupol that the dead were buried in courtyards, next to playgrounds, triggered a new activist intervention in public space. The action was called “Mariupol 5000”, corresponding with the number of dead civilians reported. Resistance members set up crosses in urban environments with inscriptions such as “Mariupol. Thousands of dead. They are buried in courtyards. The city is completely destroyed”. In recent days, more and more crosses like these have appeared in different Russian cities. On April 3, when the whole world learned about the massacre in Bucha, new crosses appeared with the inscription: “Bucha. Ordinary people were shot in the back of the head. This is not a special operation. This is genocide.”

The testimonies of Bucha and other cities in the Kiev region have shocked people. A few days ago I noticed that a Facebook friend of mine published a new profile picture: he had carved the word Bucha on his arm with a blade. Two more photos of people who made the same gesture appeared in the comments. I interpret this gesture as a representation of pain when words cannot express it.

When I asked my friend if I could publish his photo in an article on forms of protest, he replied that he does not consider it as an action of protest, but rather as an act of remembrance, which refers to the work of the Kiev artist Valya Petrova. In 2015, she put the word “Zhanaozen” (which is a city in Kazakhstan where 15 protesting workers were shot in 2011) on her back using the technique of scarring and the Braille alphabet. At “Yeah, I remember”, an exhibit in St. Petersburg in 2015, Petrova stood behind a screen, and visitors were invited to put their hand through the fabric and feel the inscription.

In an interview published in The Right to Truth: Conversations on Art and Feminism (2019), Petrova states: “A scar is something that is always with you, but you don’t see it constantly. When you see a scar on someone you ask how they got it, and this pulls out a story from the past. (...) The holes also resemble bullet holes on my back, because the oil field workers in Zhanaozen were shot in the back.”

Even if my friend argues ‘writing’ the word Bucha on his hand is not a form of protest, I read it as an act of resistance. In my view, this gesture sounds louder and brighter than spoken words, as words carved in the body cannot be blocked or canceled in any way.

04 / 04 / 2022

3 марта 2022