77 — May 2022

Ventriloquism in Beyonce’s Black is King (2020)

Nedine Moonsamy

For Africans, Black is King can induce whiplash. Cultural, physiological and geographical semiotics are scrambled to the extent that any attempt to interpret them is either infuriating or downright funny. Yet experiencing Africa through this clumsy inertia is also heartening; a reminder of how the subconscious has such a rich and complex archive of a place you call Home. This intuitive catalogue of nuanced African faces, sounds, dress, and textures is precisely what African-Americans lack and what, somewhat ironically, creates the very impulse for narratives like Black is King.

Beyonce’s latest visual album, released in 2020 on Disney+, is a contemporary capitalistic retelling of an old mythological narrative:

Zion Me Wan Go Home Zion, me wan go home, Zion, me wan go home, Oh, oh, Zion, me wan go home. Africa, me wan fe go, Africa, me wan fe go, Oh, oh, Africa, me wan fe go. Take me back to Et’iopia lan, Take me back to Et’iopia lan, Oh, oh, Take me back to Et’iopia lan. Et’iopia lan me fader’s home, Et’iopia lan me fader’s home, Oh, oh, Et’iopia lan me fader’s home. Zion, me wan go home, Zion, me wan go home, Oh, oh, Zion me wan go home.1

“Zion, me wan go home/ Africa, me wan fe go […] Et’iopia lan me fader’s home,” reads an early anonymous Rastafarian chant, a product of the Atlantic Slave Trade that so brutally ripped millions of people off the African continent and instituted this irreparable yearning for a return passage since the 16th century. The African Motherland, whose anodyne powers serve as nostalgic reprieve and spiritual compensation for the trauma of slavery, is, ultimately, a wish for wholeness and belonging. It imagines an identity that replaces grotesque historical fissure with the continuity of an unchanging, inherited lineage. That nostalgia is a product of the imagination is undeniable, but its mythological force has proven to be an immensely creative tool for Pan-Africanism, spurring on seminal thinkers like W.E.B Du Bois, Martin Delany, and Marcus Garvey, to name a few. It has also inspired the geopolitical dialogism that became central to movements like the Harlem Renaissance, the Black Power Movement, Négritude and, more recently, Afrofuturism.2

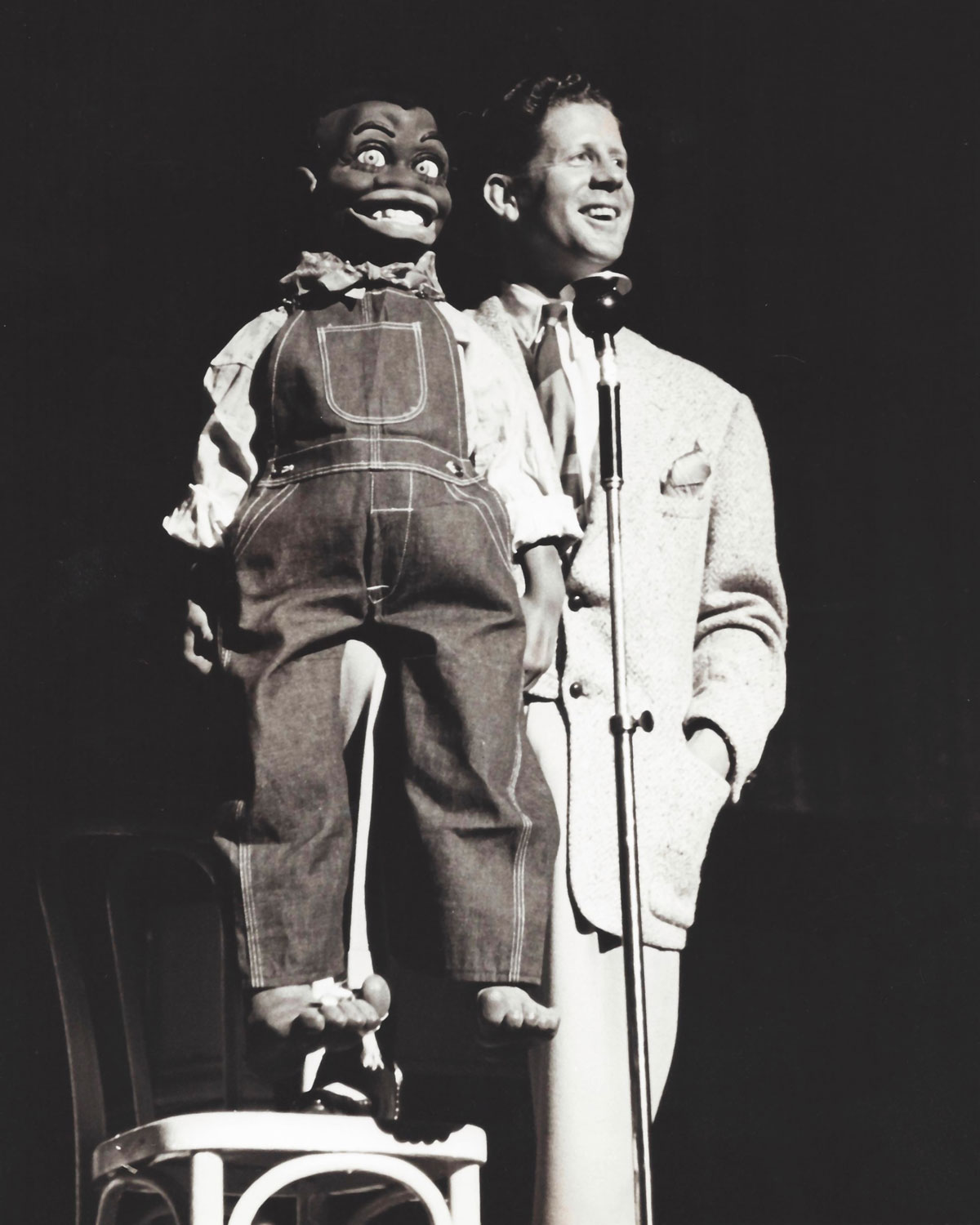

Yet Black is King shows how nostalgia can be a tricky ruse too. The lush seductiveness of fantasy that makes home a desirable place, is also what denies its return. Many travellers can attest to the fact that going back can break the spell of the imagination, making it preferable to keep the romantic veil intact. It is no surprise that the idea of nostalgia – an idyll (nostos), through an assertion of longing, return or loss (algia) – is premised on distance and unattainability, which translates often as a lack of specificity,3 like the ‘Zion’, ‘Ethiopia’ and ‘Africa’ that we see in the Rastafarian’s chant and the reliance on kaleidoscopic spectacle in Black is King. The fantasy of return is one of the displaced, and grasping at fragments of Africa in order to fashion an anodyne narrative of this kind, serves as an ironic admission of a home that one truly does not know. In this regard, the visual album offers a strange awareness of its ‘un-Africanness’ by staging what can be described as a ventriloquist’s performance.

The African cast is a generally silent and rigid ensemble. Their body movements are mechanised, robotic and sluggish – curiously, these tell-tale signs of puppets under an animator’s control are not hidden from our view. Other people’s voices and snippets of dubbed soundtrack from The Lion King literally accompany their images, as if to voice their thoughts. When mouths do open, it is still not the voice that belongs to the body that speaks; in the case of little Simba (played by Folajomi Akinmurele), Jay-Z’s rap pops out of his mouth.

Apart from the musical artists, Africa and its subjects remain on mute, and Black is King seemingly flaunts its willingness to animate Africa on its own terms. As cultural theorists like Rey Chow4 and Sianne Ngai5 outline, the aesthetics of ventriloquism and animation are paradoxical; revealing both puppet and puppet-master, they allow us to witness the artifice as show and, in doing so, make us complicit in the spectacle.

Genres like animation, cartoons, puppetry and ventriloquism all reckon with a history of problematic cross-racial embodiment, one where white performers animated black characters with not just their bodies and voices, but also their racist fantasies too. Reworking this genre in contemporary times, artists tend to satirise and subvert this tradition in their performances. For example, viewers tend towards an affirmative reading of the countless tableaus of black Africans, uncharacteristically still, submitting to a gaze of a camera that tracks towards them with more agentive fluidity than the actors themselves.

Drawing on the style established in Beyoncé’s and Jay-Z’s music video Apeshit (2018), these portraits aim at a version of undeniable black beauty that slates the canonical art world for its disparaging approach to black artistry and representation.

Yet if we think back to the Sambo doll puppet show in Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, the eponymous narrator observes how the dancing black figures are only moving because their strings are being pulled – somewhat bewilderingly – by a fellow member of the Brotherhood, but the revelation of this spectacle does not reduce the narrator’s anger.

Black is King leaves us with a similar dilemma as we, like the Invisible Man, have to wonder if there is a qualitative difference involved in witnessing that a seeming ally – already wizened to the show – is pulling the strings. In the ‘My Power’ sequence of Black is King, the space resembles an art gallery, and the South African musician, Busiswa, appears inside a large white frame, dressed in a colourful costume that exaggerates her bosom and buttocks in a way that overtly resembles Sara Baartman.7

The visual album cites awareness of the kind of pedestal that black women’s bodies have been placed on – it shows us the show – but the tonal register of the repeated spectacle does not shift towards reversal of the comic or the kind of reverence that the visuals sometimes achieve in ‘Brown Skin Girl’. Just like the narrator in Invisible Man, we are invited to the ventriloquist’s show, but only to bear witness to how fabrication transmutes into fact; he is also a puppet on a string, he realises, caught in a spectacle that has no conceivable end.

So it follows that the more recent waves of #BlackLivesMatter marked a fissure between African-Americans and Africans; there were fewer, and smaller, protests in Africa in comparison to the rest of the world and absolutely no reaction from the West in response to more recent Zimbabwean, Ugandan and Ethiopian outcries; a sign that black solidarity feels like a cruel joke when the Global North loves you like Beyoncé. In the ‘Mood4Eva’ sequence that settles on a display of monarchical splendour, Beyoncé faces the camera telling the viewer to ‘stay in your struggle’. This serves as a cruel reminder to an impoverished continent that this story is hardly about them but rather an imaginative backdrop against which African-American freedoms are measured and portrayed.

Notes

- 1Anon. in Burnett, Paula (ed). The Penguin Book of Caribbean Verse. Penguin: London, 1986, 30.

- 2See Commander Michelle D (2017) Afro-Atlantic Flight: Speculative Returns and the Black Fantastic. Durham: Duke University Press, and Pierre, Jemima (2013) The Predicament of Blackness: Postcolonial Ghana and the Politics of Race. London and Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- 3Boym, Svetlana (2001), The Future of Nostalgia. New York: Basic Books.

- 4Chow, Rey (1992) ‘Postmodern Automatons’ in Butler, Judith and Scott, Joan (eds), Feminists Theorize the Political New York and London: Routledge, pp 101-117

- 5Ngai, S. (2005). Ugly feelings. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

- 6Image Anon. Found on The Alan Ende Ventriloquist Website. Accessed on 12/05/2022.

- 7For more information see Ashle, Rokeshia Renné, “How Sarah Baartman’s hips went from a symbol of exploitation to a source of empowerment for Black women” on The Conversation. Published: 15 July 2021.

- 8Image Anon. Found on Feminist Miranda Blog, “SARAH BAARTMAN SAARTJIE”. Published: 4 February 2019.