6 – January 2017

clustered | unclustered

a

clustered | unclusteredColonial Monuments and Post-Colonial Memories: Reflections on a Monument in Geraardsbergen

Robert Aldrich

Invited to contribute some observations on the monument in the Grupello park in Geraardsbergen, I must confess that I am unfamiliar with the site and indeed with the town, although I have written about similar lieux de mémoire in France, elsewhere in Europe and in former colonies.1 I dare say many Belgians are themselves unaware of this commemoration of Africa in Flanders. That lack of familiarity, however, provides an insight, both about the ardent desire of men and women of the past to celebrate for posterity the experiences of those involved in colonial endeavours and the extent to which people today have difficulty recollecting the history of European overseas expansion. Promoters of colonialism erected statues of explorers, soldiers, missionaries and administrators, in pride at what were considered their heroic achievements, in grief at their sacrifices and deaths, and in determination to convince and remind compatriots of the benefits to Europeans and native peoples of imperial rule. They were, of course, part of the propaganda of colonialism. Since the end of empires, some of these monuments have remained obstinately standing, others have been removed or vandalised, but yet others have simply been forgotten or are ignored. Pedestrians dart around statues at crossroads or pass by them in parks but pay little real attention to them, and time effaces inscriptions and takes its toll even on marble, cement and stone. As colonialism receded deeper into the past, the monuments seemed phantoms of a history that many have not particularly wanted to remember.

Colonialism, in Belgium and elsewhere, however, returned to haunt the legatees of empires. Adam Hochschild’s King Leopold’s Ghost, published in 1998, provided shocking details – some already well known to scholars, others largely new to general readers – about the Congo Free State. In 2007, Memory of Congo: The Colonial Era, a major retrospective at the Africa Museum in Tervuren, displayed Belgium’s vast African empire to present-day citizens. The book and the museum reopened and provoked intense debate about the colonial past and its heritage, about historical and curatorial approaches to imperialism, and about current policies. When the Africa Museum closed in December 2013 for a five-year renovation, it was a sign of determination to reconceptualise and bring up to date this grandiose temple of colonialism erected by King Leopold II. Debates surrounding the Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac in Paris and the MUCEM in Marseille, the short-lived and conflicted existence of a British Empire and Commonwealth Museum in Bristol, such exhibitions as ‘Artist and Empire’ at Tate Britain in 2015, and one on German colonialism that opened at the Deutsches Historisches Museum in Berlin in October 2016 testify to renewed and continuing but contested interest in colonialism as a subject. They also point to the demand for individuals, collective groups and countries to come to terms with the colonial past.

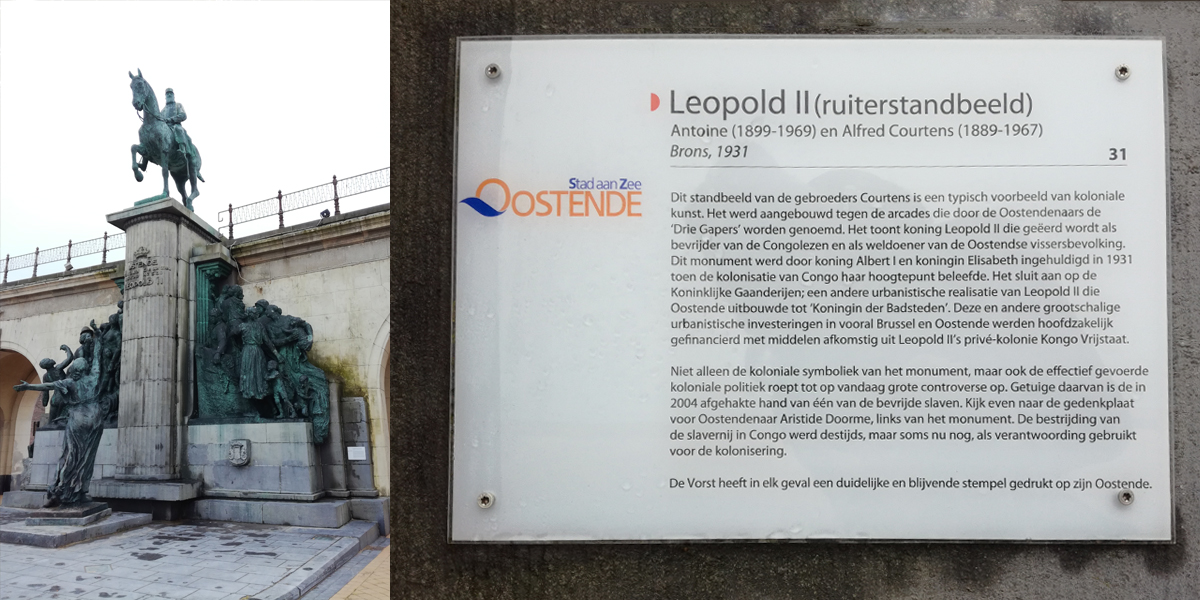

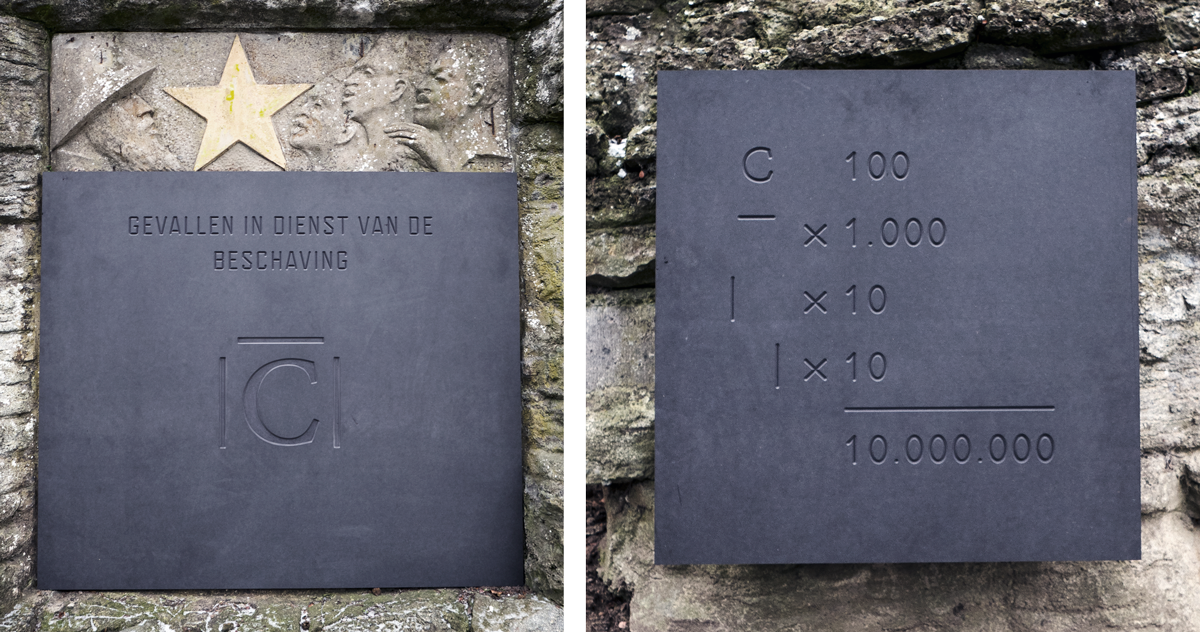

I know little about the men commemorated in Geraardsbergen – web searches turn up some information on the sculptor and photographer Théophile L’Haire, but little on Father Jules Van Trimpont or Walter-Willy Martens. Yet lack of details does not mean that a passer-by, or a scholar, cannot reflect on such a monument, for monuments in principle are meant to be both legible and pedagogic. Monuments, like tombstones, often commemorate individuals, and it is not coincidental that public monuments in the form of plaques or obelisks often resemble those found in graveyards, with stone tablets inscribed with names and dates, and brief words of tribute. Here in Geraardsbergen we have, potently, figures from the high age of colonialism and the time of decolonisation. A Catholic priest and, I presume, some of his collaborators or parishioners, or at least fellow townsmen, come from the very first years of the twentieth century, and no doubt carried out their mission of evangelisation in Central Africa. The priest and his eight associates were honoured for having ‘fallen in the service of civilisation’, the rather vague phrase using the usual euphemistic tribute for warriors – ‘fallen’, rather than ‘killed’ – and conflating, as colonialists did, Christianity, colonialism and civilisation. The iconography reinforces the words, the star of the Congo Free State – like the Star of Bethlehem – centred between the kindly looking, bearded, pith-helmeted priest, while three Africans, appearing to be a native holy family of father, mother and child, look reverently at the man whose sacerdotal function was to bring Christ to the heathen. A newer plaque honours a conscripted soldier, a native son of Geraardsbergen, who also died in service, near the end of empire, in 1960, two years before Burundi attained independence. The two lives seem complementary: the young man and the old, the soldier and the priest, the ‘pioneer’ bearing the standard of Christ and the flag of conquest, and the youthful soldier fallen just not long before the colonial flag was lowered.

The monument, which I’ve learned was commissioned by a colonialist association, was unveiled in 1949, a moment when Belgian and other European nations were recovering from the Second World War and hoping that the resources of their colonies would offer ways of re-establishing their battered economies and social orders, and a means of buttressing their diminished role in world affairs. Colonialism nevertheless was being challenged with increased vigour, and often successfully so: by 1949, Britain had quit India, the Netherlands had finally recognised the independence of Indonesia, France was engaged in a doomed attempt to retain its empire in Indochina. Policy-makers thought it would be many decades, or even longer, however, before the sub-Saharan African countries would become independent or autonomous. The new world order nevertheless demanded remodelled administration, greater investments and changed attitudes, though African nationalists would not long remain content with these changes, and colonialism hung in the balance.

The plaque in honour of Martens, affixed after his death in 1960, eerily has much space left empty. Did the monument-makers foreshadow that other soldiers would fall in battles in Central Africa, or would die in trying to preserve the remnants of Belgium’s empire or in intervening in political, regional and ethnic conflicts in the Lakes region? The blank space on the slate is a reminder that colonial conflicts endured well into the 1960s and still later, in black Africa, in East Timor and West Papua, in Palestine and Tibet. Many of those who died have no monument, and their names remain unrecorded.

The monument, like many others, includes a regional coat of arms and a rather curious bas-relief of a mythological horned and bearded man – an emblem that I cannot really interpret from afar – on the front of an altar-like or perhaps coffin-like structure, the rocks on top of which make it look like some sort of cairn. However, the iconographical element that attracts my attention is the elephant, its trumpeting trunk arched over its back as it strides forward atop a tall dry-stone ridge, and I would like to dwell on that image. Since the time of Alexander the Great and Hannibal, elephants have fascinated Europeans. The massive African elephant and its smaller-eared Asian cousin are symbols of their continents, but also of power, majesty and overlordship. Now favourites of tourists who want to pat, feed and ride them while on holiday, they were (and in some places still are) beasts of burden in forests and jungles, and they produce the coveted ivory so prized for ornamentation. Ivory was one of the main trading goods of interest to Europeans, turned into objets d’art of extraordinary value and often breath-taking beauty. Taking ivory, of course, meant slaughtering elephants, sport for big-game hunters, business for even more rapacious traders and poachers – a horrifying practice that continues even with international prohibitions on the sale of ivory. Elephants, whose tusks were turned into fine art and gaudy baubles, whose feet sometimes ended up as umbrella stands or wastepaper baskets, and whose hides covered cushions and sofas, are now, rightly, objects of great concern, interest and affection for conservationists as their numbers decline and their natural environment is destroyed. Scientists continue to reveal the complexities of elephant life, and – as the cliché has it – elephants never forget: that makes the pachyderms a striking motif for monuments.

Elephants entered European iconography very early, appearing on antique sculptures and ornamenting columns in medieval churches. Renaissance patrons liked elephants, as witnessed by a sculpture of Hannibal’s tower-topped elephant erected in the Bomarzo gardens in Italy in the mid-1550s, and an elephant used, in the mid-1600s, under the reign of Pope Alexander VII, as the base for an obelisk brought from Egypt to Rome as early as the first-century reign of Caligula. (It still stands, picturesquely, in the Piazza della Minerva.) After Napoleon’s return from his Egyptian campaign – which played a seminal role in promoting ‘Egyptomania’ throughout Europe – he ordered the construction of a giant elephant to be placed on the site of the demolished Bastille fortress and prison. The final sculpture was never built, but a wooden and plaster model was indeed completed, and for thirty years ornamented the Place de la Bastille, evoked by novelists, enjoyed by tourists, and said to be the refuge for ne’er-do-wells (and rats) until it was destroyed in 1846.

Elephants were symbols of exotic nature and superhuman power, sometimes adopted as heraldic emblems – the premier Danish order of chivalry is the Order of the Elephant and the entrance to the old Carlsberg brewery in Copenhagen is festooned with impressive elephants. Elephants were, too, symbols of the authority and wealth of foreign potentates, the bejewelled maharajas who rode on caparisoned elephants in India, and the sacred white elephants of the sovereigns of Burma and Thailand. Live elephants appeared at European zoos and circuses (though they were not always well treated and were sometimes cruelly abused), and thanks to the taxidermist’s art, deceased ones stood in museums of natural history. Elephants also appeared in popular culture, often as advertising for tobacco, chocolate, tea or other tropical products. Elephants in the nineteenth century increasingly and intentionally became associated with colonial conquest, with the subjection of Africa by Europeans. Statues of elephants triggered in bystanders’ minds images of the African savannahs, but also of European dominion over Africa, its people and its fauna. In the Albert Memorial, constructed in London in 1872 in memory of Queen Victoria’s Prince Consort, an elephant appears in the representation of Asia, surrounded by an Arab or Indian, an East Asian and a nubile bare-breasted woman. The French commissioned a statue of an elephant (among other animals) for the 1878 exposition coloniale, one of the first Paris world fairs that featured pavilions dedicated to the colonies. (That elephant now stands outside the Musée d’Orsay.) Elephants by the early twentieth century became a vogue for monuments linked to colonialism, and indeed in the whole imagery of the exotic and the colonial. Jean de Brunhoff’s Histoire de Babar, le petit éléphant first appeared in France in 1931 and recounted the tale of an orphaned elephant that ventures to the city and subsequently returns to his herd bringing the benefits of civilisation. An impressive elephant statue was unveiled in Bremen in 1932, as a memorial to German soldiers killed in war and also as a memorial to Germany’s ‘lost’ colonies – a significant gesture at a time when many on the political right championed the recovery of Germany’s overseas empire. In 1935, a grand statue of an elephant, controversially sponsored by the Côte d’Or chocolate company, was placed outside the Africa Museum in Tervuren. In 1937, the city of La Rochelle erected a monument to several ‘pioneers’ of French colonialism in western Africa, with bas-reliefs of elephants saluting medallion portraits of ‘three peaceful conquerors of the Côte d’Ivoire’, a map of Africa and two traditional masks and sceptres underlining the geography and the history. These examples are but a small selection of elephants in European monuments that made explicit and pregnant reference to colonies won and lost, and to the confluence of elephants, exoticism, conquering power and imperialism in the iconography.2

Colonialism is remembered in much statuary in Belgium, as it is in Britain, France, Spain, Portugal, and to a lesser degree in Italy and Germany. There is the colonial monument in the Cinquantenaire Park in Brussels, the statue of an African woman and child (dedicated ‘A nos vétérans coloniaux’, 1876-1908, in the city hall of Charleroi), an African woman and child, also, but this time picking fruit in the forest, in Mons (‘A nos pionniers’), or the column surmounted by an African head in Ixelles. There is the statue of Leopold II in Arlon (inscribed ‘J’ai entrepris l’oeuvre du Congo dans l’intérêt de la civilisation et pour le bien de la Belgique’), and the many other statues of Leopold II, some occasionally spattered with red paint, marked with graffiti or with bits hacked off as signs of activist historical commentary. Matthew G. Stanard’s historical works have shown how statuary was part of the project of ‘selling the Congo’, but could also serve as points for expressions of anti-colonialism.3 The art historian Deborah Silverman has persuasively argued that, more subtly, Africa – and Belgian colonialism in Africa – provided key motifs in modernist artistic movements in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Belgium.4 And Idesbald Goddeeris has looked at the particularities of postcolonial Belgian reactions to colonial propaganda.5 These and similar works help us understand how the legacies of colonialism have been assimilated, occluded or confronted.

What to do now with historical monuments glorifying colonialism is a contested issue, both in Europe and in the colonies, especially when the figures represented, once as great heroes, are now seen as far less than noble. The issue has arisen, for instance, with statues of Cecil Rhodes in Britain and General von Heutsz in the Netherlands, and commemorations of defenders of Algérie française in France. In cities such as Amsterdam, Paris and London, there are now monuments to enslaved Africans, and gradually there are memorials to victims of particular colonial wars and massacres, but still relatively few to colonised subjects in general. In one significant postcolonial gesture – and, in my view, one of the most poignant – the Bremen colonial monument, the 1932 elephant, was in 1990 rebadged as an anti-colonial monument, and six years later the Namibian president, Sam Nujoma, unveiled a new plaque at the monument in memory of ‘Victims of German Colonial Rule in Namibia, 1894-1914’.

Leaving monuments unamended risks perpetuating the stereotypes and falsehoods of the colonial age. Yet iconoclasm can be very dangerous, too, for destroying or removing monuments suggests polarities between those inducted into pantheons and those expelled, the replacement of old orthodoxies with new ones, and the promulgation of sanctioned historical narratives; it erases history from landscape, and it can destroy genuine works of art. Another kind of revision of monuments – with new explanatory plaques and signage, explicit rejection of offensive language and sentiments, supplementary documentation made possible through new technology – can more helpfully contextualise old statues and memorials, and turn them into cautionary tales for contemporaries. An elephant, even one triumphantly erected in honour of colonial conquest, can be re-presented as a symbol both of the resilience of African cultures against colonialism and a powerful statement about the need to safeguard Africa’s nature from human and environmental depredations. The names of a priest, a soldier and other men who had links to Geraardsbergen and who died in Africa – though we now do not think of them having fallen ‘for civilisation’ – still record the bereavement of families and communities (and the honour given to L’Haire, an acclaimed local artist and photographer), but one should think, too, and record expressions of sentiment, about those who fell as victims of the ‘civilising mission’. Both in Europe and outside Europe, an understanding of colonialism is necessary because of the impact that phenomenon had and continues to have on the world. Looking at colonialism is not, I think, a question of apportioning blame or drawing up indictments. Expressions of regret, saying sorry for deeds done, is sometimes appropriate and justified, and this has special pertinence when gestures relate to particular circumstances and groups.6 Such expressions may be requested and expected from both those who were colonised and from those who did the colonising, for culpability is not restricted to one side or the other. But the force of arms and the doctrine of colonial conquest and rule, and the efforts to maintain empire, place much of the burden on the shoulders of the former colonisers. Acknowledgement of the colonial past does not constitute self-flagellation for misdeeds nor is it a tokenistic sign of ‘political correctness’. It is recognition of historical events, a critical examination of the perspectives of the past and an invitation to consideration of our own attitudes and policies. Monuments relating to colonialism are reminders of a past that is still recent – if Walter-Willy Martens had not died in Africa, he might now be thriving in contented retirement in Geraardsbergen. But as European societies are confronting grave questions about refugees and migrants, about terrorism and intractable bloody conflicts around the world, such monuments are also valuable injunctions to address racism and intolerance, exploitation and war, fanaticism and violence in our own times.

Notes

- 1 Robert Aldrich, Vestiges of the Colonial Empire in France: Monuments, Museums and Memories (London, 2005), and an updated French edition, Monuments et mémoires: Les traces colonials dans le paysage français (Paris, 2011); ‘Commemorating Colonialism in a Post-Colonial World, E-rea, 10.1 (2012), online at www.erea.revues.org/2803.

- 2 There are various historical works on elephants and colonialism; a particularly perceptive study is Sujit Sivasundaram, ‘Trading Knowledge: The East India Company’s Elephants in India and Britain’, The Historical Journal, Vol. 48, No. 1 (2005), pp. 27-63.

- 3 Matthew G. Stanard, Selling the Congo: A History of European Pro-Empire Propaganda and the Making of Belgian Imperialism (Lincoln, Nebraska, 2012), esp. Ch. 5, and ‘King Leopold’s Bust: A Story of Monuments, Culture, and Memory in Colonial Europe’, Journal of Colonialism and Colonial History, Vol. 12, No. 2 (2011).

- 4 Deborah Silverman, ‘Art Nouveau, Art of Darkness: African Lineages of Belgian Modernism’, West 86th: A Journal of Decorative Arts, Design History, and Material Culture’, Part I, Vol. 18, No. 2 (2011), pp. 139-181, Part II, Vol. 19, No. 2, pp. 175-195.

- 5 Idesbald Goddeeris, ‘Colonial Streets and Statues: Postcolonial Belgium in the Public Space’, Postcolonial Studies, Vol. 18, No. 4 (2015), pp. 397-409.

- 6 In the case of my own country, Australia, I think of the moving apology made in Parliament by then Prime Minister Kevin Rudd in 2008 to the ‘stolen generations’ of Aboriginals, children who had been separated from their families over many decades.

b

clustered | unclustered6936 gaps

Ode de Kort

c

clustered | unclusteredEen einde aan de koloniale propaganda

Idesbald Goddeeris

“Het monument ‘Den Olifant’ werd gemaakt door de Geraardsbergse kunstenaar Théophile L’Haire in 1948. De inhuldiging vond plaats op 10 juli 1949. Het is geen eerbetoon aan het koloniaal verleden, maar een gedenkteken voor Geraardsbergenaars die het leven lieten in Congo.”

Als het gemeentebestuur van Geraardsbergen het advies volgt van zijn departement Cultureel Erfgoed, zal de bovenstaande tekst aan het koloniale monument ‘Den Olifant’ worden toegevoegd. Hij zal geplaatst worden op ‘een glazen bordje, gelijkaardig aan de huidige toeristische informatieve bordjes’. Dat zou een gemiste kans zijn. Een struisvogelpolitiek. Een ontkennen van de waarheid.

Onwaarheden

Het monument ‘Den Olifant’ is wél een eerbetoon aan het koloniaal verleden. Dat staat buiten kijf. De olifant lijkt onschuldig, maar het plakkaat eronder windt er geen doekjes om. De goudgele ster verwijst naar de vlag van de Congo Vrijstaat (1877-1908) en van Belgisch Congo (1908-1960). Links daarvan is een wijze koloniale blanke gebeeldhouwd, zwijgend, met lange baard en tropenhelm. Aan de andere kant kijken drie zwarten hem aan, zingend, erend, een hand op de schouder van verenigde dankbaarheid. En onder dit tableau wordt het nog eens expliciet gesteld: het monument eert negen Geraardsbergenaars, ‘gevallen in dienst van de beschaving’.

‘In dienst van de beschaving’… Met die woorden werd koloniale expansie telkens opnieuw gelegitimeerd. De continenten buiten Europa werden bewoond door primitieven, wreedaards, slavenhandelaars en ongelovigen, en het was de taak van de blanke – de white man’s burden – om die wantoestanden de wereld uit te helpen. Althans, zo wilden we het geloven. In feite dreven Europeanen elf miljoen Afrikanen de slavernij in, roeiden ze hele bevolkingsgroepen uit met wapens en ziektes, en voerden ze een roofeconomie in, waarvan de gevolgen tot op de dag van vandaag blijven nazinderen.

Ook de Belgen in Congo. Het regime van Leopold II heeft miljoenen slachtoffers geëist en was een van de meest moordzuchtige van zijn tijd. Moeten de Geraardsbergenaars die daaraan meegewerkt hebben, echt geëerd worden?

De Congo Vrijstaat werd al snel het mikpunt van internationale kritiek. Die werd zo luid dat de Belgische vorst in 1908 afstand moest doen van zijn kolonie. De Congo Vrijstaat werd Belgisch Congo. De koloniale pioniers kregen echter snel eerherstel. Het kolonialisme bloeide in de jaren en decennia na de Eerste Wereldoorlog, en koloniale lobbygroepen lieten overal in België monumenten en herdenkingsplaten oprichten voor de ‘helden’ van de Congo Vrijstaat. De Amerikaanse historicus Matthew G. Stanard telt er 47 uit de jaren dertig, en meer dan 20 uit de vijftien jaar tussen de Tweede Wereldoorlog en de Congolese onafhankelijkheid.

Geraardsbergen bleef niet achter in deze campagne van maatschappelijke mobilisatie en koloniale propaganda. De Cercle Colonial-Grammont richtte zijn monument op in 1949. Het eert negen Geraardsbergenaars die ‘gevallen zijn in dienst van de beschaving’, maar neemt een loopje met de feiten, want verschillende van hen zijn in België gestorven. Het monument is dus op meerdere niveaus een radicale vertekening van de waarheid. De namen van gevallen koloniale pioniers. De boodschap van beschaving. En binnenkort ook het informatiebordje? ‘Geen eerbetoon aan het koloniaal verleden, maar een gedenkteken voor Geraardsbergenaars die het leven lieten in Congo’?

Informatiebordjes

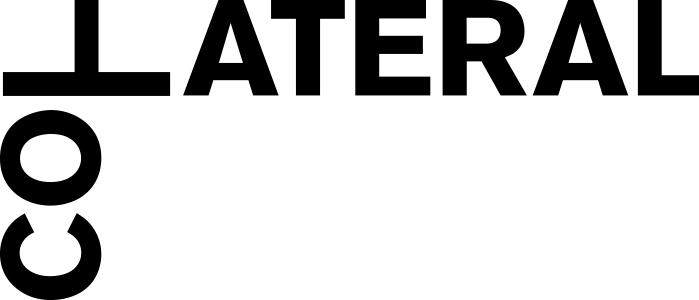

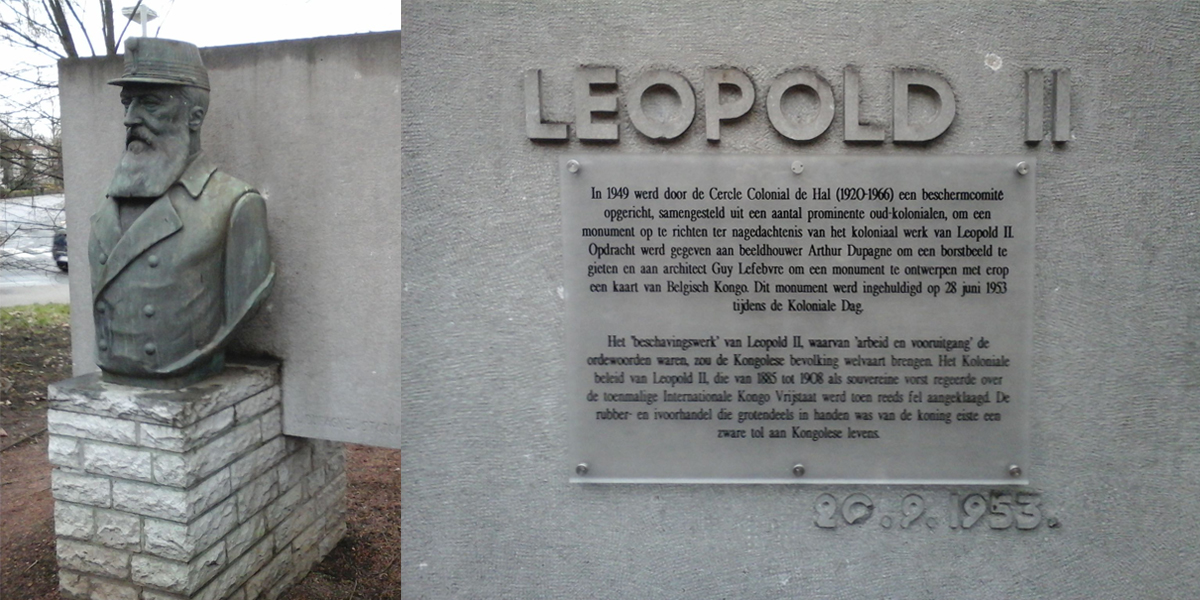

Geraardsbergen is niet de eerste stad die een infobordje plaatst bij een koloniaal monument. In september 2009 deed Halle dat al bij een borstbeeld van Leopold II. Wilrijk volgde in mei 2015 bij een standbeeld van missionaris Constant De Deken dat sommigen als racistisch ervaren omwille van de zwarte Afrikaan die onder de knie van de blanke pater buigt. In september 2016 kreeg het veelgeplaagde ruiterbeeld van Leopold II op de zeedijk in Oostende een nieuwe toelichting. Gent kondigde er in diezelfde maand ook eentje aan, maar dat staat er drie maanden later nog steeds niet. Ook in 2004 had de stad al zo’n belofte gedaan en niet ingewilligd.

Zulke informatiebordjes kunnen het protest tegen deze standbeelden weliswaar wat ontmijnen, maar een ideale oplossing vormen ze geenszins. Ten eerste is het moeilijk om een gepaste tekst te schrijven. Halle slaagt daar het best in: het plaatje situeert de totstandkoming van het monument en erkent de ‘zware tol aan Kongolese levens’. Wilrijk draait rond de pot: pas na meer dan tien zinnen over Tibet en andere zaken die naast de kwestie zijn, geeft de stad aan dat het beeld uit 1904 ‘uitdrukking geeft aan de toenmalige verhoudingen tussen Europeanen en Afrikanen in de Onafhankelijke Congostaat’. Oostende is explicieter en noemt zijn monument ‘een voorbeeld van koloniale kunst’. Maar het infobord slaat niet alleen, het zalft ook: het erkent de controverse, maar neemt geen standpunt in en besluit: ‘De Vorst heeft in elk geval een duidelijke en blijvende stempel gedrukt op Oostende.’ Geraardsbergen zou zelfs een stap terug zetten en gewoonweg ontkennen waar zijn beeld in feite voor staat.

Een tweede probleem is de plaats die zulke informatiepanelen krijgen. Halle hing het stevig vast aan het monument en gaf het een duidelijk zichtbare plek. De andere lokale besturen waren minder recht voor de raap. Wilrijk plaatste een liggend bord bij het beeld van De Deken. Geen goede keuze: het valt minder op en was na een half jaar al verweerd door de tijd. Oostende nam zijn plaatje op in een reeks van informatiebordjes bij toeristische bezienswaardigheden, een oplossing die ook Geraardsbergen al in gedachten heeft. Dat is handig, want Oostende heeft twee monumenten voor Leopold II. Het tweede informatiebordje maakt echter geen melding van kritiek en geeft alleen details over de geschiedenis van het beeld. Het compenseert zo de postkoloniale kritiek met een veelvoud aan meer comfortabele feiten.

Informatieplaatjes nemen het onbehagen rond het koloniale verleden dus niet weg. Zowel wat de inhoud als de vorm betreft, zijn het schaamlapjes, die niet openhartig afstand nemen van de wandaden en de agressieve propaganda van het verleden. Alleen Halle is een uitzondering, maar dat komt vooral omdat de kritiek op het monument communautair geladen was en de stad aan de taalgrens gevoelig is voor zulke kwesties.

Een museum van koloniale propaganda

In de buurlanden heeft men andere oplossingen gevonden voor koloniale monumenten. Sommige standbeelden hebben een nieuwe betekenis gekregen. Het Reichskolonialehrendenkmal in Bremen – net als in Geraardsbergen een olifant – werd in 1990 herdoopt tot het Antikolonialdenkmal; het standbeeld voor Johannes Van Heutsz – de ‘pacificator’ van Atjeh – in Amsterdam werd in 2007 getransformeerd tot het Monument Indië-Nederland. Een tweede strategie is de bouw van nieuwe standbeelden, die ook slachtoffers en antikoloniale voormannen erkennen. Londen huldigde in maart 2015 op Parliament Square, te midden van zijn pantheon van grote namen uit de Britse geschiedenis, een monument in voor Gandhi, overigens al het tweede na dat op Tavistock Square uit 1968. Lumumba is in de Belgische openbare ruimte nog steeds persona non grata, maar kreeg de voorbije jaren standbeelden in Berlijn (2013) en in Leipzig (2010, een restauratie van een borstbeeld dat in 1997 beschadigd en nadien gestolen werd).

Een derde manier om met het koloniale verleden om te gaan, is om standbeelden gewoon te verwijderen. In verschillende ex-kolonies worden de oude monumenten dan samen gezet in een park (bv. in Delhi) of in een museum (bv. in Kinshasa). Vergelijk het met de bekendere verzamelingen communistische standbeelden, zoals Grūtas Park in Litouwen, Memento Park in Hongarije of MUZEON in Moskou.

Een museum van koloniale propaganda? Zou dat geen betere oplossing zijn voor de Belgische monumenten? Er bestaat al een eerste aanzet in een uithoek van het openluchtmuseum in Middelheim, maar de koloniale beelden staan er samen met andere beelden waar men geen blijf mee weet en worden bovendien nergens als dusdanig geafficheerd. Zo’n koloniaal beeldenpark zou beter passen in het Koninklijk Museum voor Midden-Afrika van Tervuren. Dat is net aan een grondige restauratie bezig. Zou er geen deel van het park gebruikt kunnen worden voor afgedankte standbeelden uit de koloniale periode? Zoiets zou een unicum zijn: geen enkele koloniale metropool is al zo ver gegaan. België – in de internationale koloniale geschiedenis vaak voorgesteld als één van de slechtste leerlingen van de klas – zou meteen op de voorste bank komen te zitten.

Op dit moment gebeurt het omgekeerde. Gecontesteerde gedenktekens zoals het Koloniale Monument in het Jubelpark in Brussel worden in alle stilte gerestaureerd. Beelden die tientallen jaren hadden liggen verkommeren in een hoekje, krijgen een nieuwe, meer centrale bestemming. Genval plaatste in 2005 een borstbeeld van Leopold II op een nieuw ingericht pleintje. Deinze deed in 2008 hetzelfde met een monument voor Jules Van Dorpe (die tussen 1895 en 1898 een vrijwilligersleger leidde in de Congo Vrijstaat en in die functie actief betrokken was bij Leopolds regime van dwangarbeid en terreur).

Stellen dat de omgang met ons koloniaal erfgoed geen prioriteit kan hebben in tijden van crisis en onzekerheden, is dus zand in de ogen strooien. In plaats van dergelijke monumenten in ere te herstellen, zouden we de middelen beter gebruiken om hen in de juiste context te plaatsen en hen naar een museum te verhuizen. Want deze beelden getuigen van een zeer eenzijdige kijk op het verleden. We roepen elke dag op tot dialoog, maar blijven met onze herinneringspolitiek aan één dominante stem het woord geven.

31 december 2016

Meer lezen

- — ‘Advies koloniaal monument “De Olifant”. Nota aan het college van burgemeester en schepenen’ (Departement Vrije Tijd – Cultureel Erfgoed; dossierbeheerder: Jan Coppens; zitting van 17 oktober 2016), zie onder meer ook TV OOST.

- — ‘Na jaren protest: eindelijk “excuusbord” voor Leopold II’, Nieuwsblad (27 september 2016)

- — ‘Nieuw infobord bij omstreden standbeeld van Leopold II in Oostende’, Deredactie.be (11 september 2016).

- — Dirck Surdiacourt / Marc van Trimpont, De Witte Congo. Congo ya pembe (Gerardimontium 2008).

- — >Matthew G. Stanard, Selling the Congo. A History of European Pro-Empire Propaganda and the Making of Belgian Imperialism (Lincoln NE 2012) (de geciteerde getallen p. 179-180).

- — Idesbald Goddeeris, ‘Square de Léopoldville of Place Lumumba? De Belgische (post)koloniale herinnering in de publieke ruimte’, in: Tijdschrift voor Geschiedenis, 129/3 (2016), 349-372.

d

clustered | unclustered10.000.000

Arne De Winde & Lieven Van Speybroeck

Geachte dames en heren,

Vandaag brengen we hulde aan Den Olifant, het monument der Pioniers, gemaakt door Théophile L'Haire in 1948 in opdracht van de Koloniale Kring, officieel ingehuldigd in 1949. We brengen hulde door het ernstig te nemen, door het de aandacht te schenken die het verdient.

Zeggen dat De Olifant geen vragen opwerpt – en daarmee basta –, doet De Olifant oneer aan. Hij verdient beter, hij verdient in al zijn complexiteit overdacht te worden en niet tot één waarheid gereduceerd te worden. Vandaag verklaren we De Olifant dan ook open voor interpretatie. Laten we kijken, laten we lezen.

Het is een relict uit een tijd die nog niet vervlogen is – en dat ook nooit zal zijn. Zoals ook een olifant zelf nooit vergeet, legt dit beeld een onuitwisbaar spoor in de stad.

Wie heeft wie beschaafd? En ten koste van wie of wat? En wat is die beschaving waarvoor men valt? Het gaat daarbij niet alleen om cijfers, laat staan hen tegen elkaar op te wegen.

Het is een tijdsdocument, maar dan wel een dat ook onze tijd betreft. Laten we De Olifant niet afbreken, besmeuren, verstoppen of met een infobord het stilzwijgen opleggen, maar laten we dit als een ontmoetingsruimte zien. Een plek waar we heel diverse gedachten en visies kunnen uitwisselen.

Huldigingsrede 'Den Olifant'

7 januari 2017