111 — May 2025

Reading Rubbish: Re-tracing Kasper Andreasen’s High Capacity

Sébastien Conard

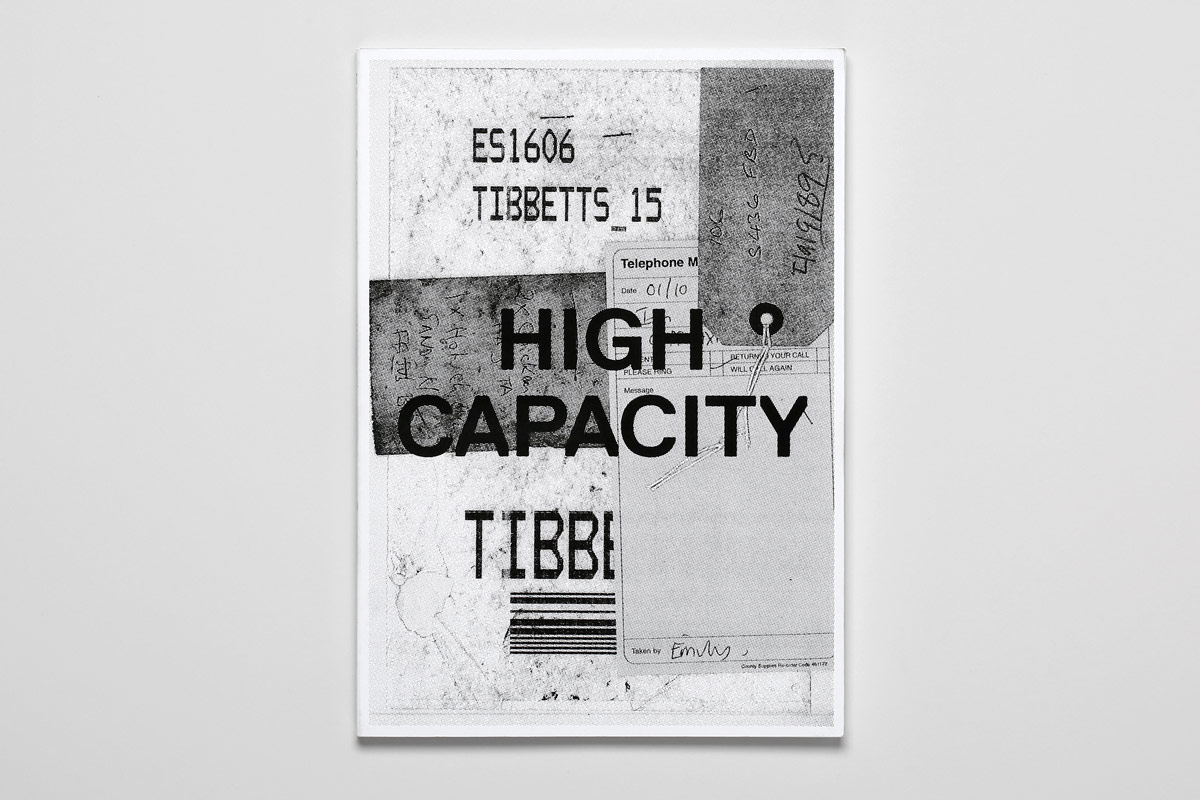

Why is Kasper Andreasen’s most recent artist’s book titled High Capacity (Roma Publications, 2023)? Is the mid-fortysomething, ‘midcareer’ artist I got to know over the years as a clever and friendly colleague meaning that he now fully operates at high capacity? Or does the title (also) imply a critical and ironic take on the pace late capitalism took since a couple of decades? This keenly designed and well-published compilation of “offcuts, scraps and traces of printed material” collected between 1998 and 2003, as the Danish-born artist states in his introduction, seems to comply with different interpretations. Though he started collecting found leaflets rather “naively” as a teenage art school student in London, the result of his continued paper hoarding appears as his most ‘mature’ work up till now. This “amassment of printed matter left from the turn of the century” is thus mainly the product of years of compiling from society’s unconscious refuse heap. Through its secure montage tactics, it indeed delivers “a very dense (compressed) image of that time” and fully contributes to the general impression of a ripened redaction I was struck by.

Stream of everything

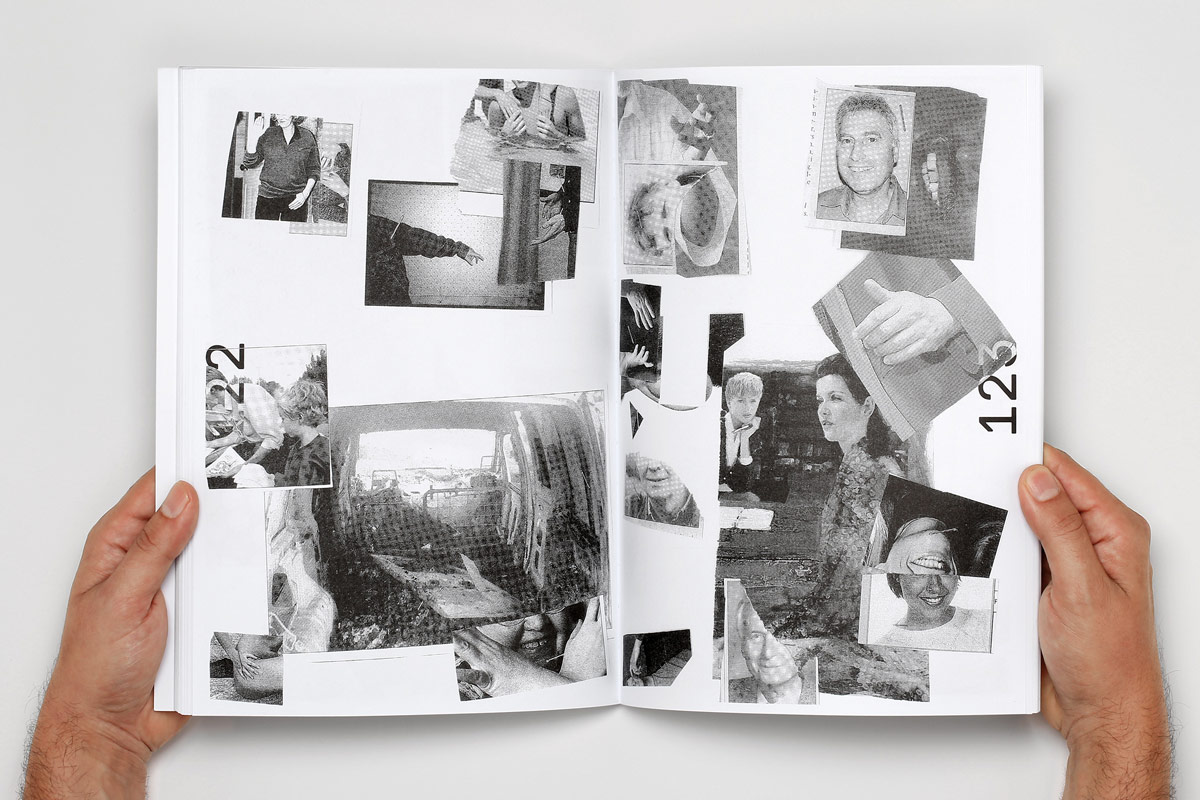

At first glance such a book doesn’t seem to be truly ‘readable’, but only made to be repeatedly flipped through, just like we zapped through boring tv channels in the nineties, constantly creating our own televisional compilation, our own ‘reading’ of the world’s latest nonsense. We were wallowing in postmodernism’s mix of high and low then, skipping through whatever came our way from that massively developed pop-cultural apparatus. It fueled us with bits of opera but mostly images of monster trucks, MTV pool contests, late-night soft erotica, upcoming reality tv, silly gag shows, the war in Iraq, etc. These manifold audiovisual fragments were constantly interceded with comics, cd’s, magazines and so on. A constant stream of everything was around us, and we became part of it. Andreasen experienced this era as a teenager, moving from Denmark to London, Amsterdam, Ghent, Brussels, and Berlin. Skimming through High Capacity, one immediately gets the impression of an authorial ‘voice’, a compiling and stapling ‘hand’, which is as compulsive as it is actually lost amidst all that stuff. Being a nineties kid myself, but slightly younger, such an approach strongly resonates, only to find myself once again the very subject of this book. In this sense, the maker or author appears to be nothing but an imagination, a distant instance that has erased itself and just left this bunch of copies behind. Who, young or old, would not relate to such a messy mix, whether you used to scavenge through your neighbor’s bin or grew up sucking on news threads, online community chats and video feeds? More broadly, who can deny that endless citation, combination and relocation has become the very ‘foundation’ of our cultural activities today?

Late postmodern mapping

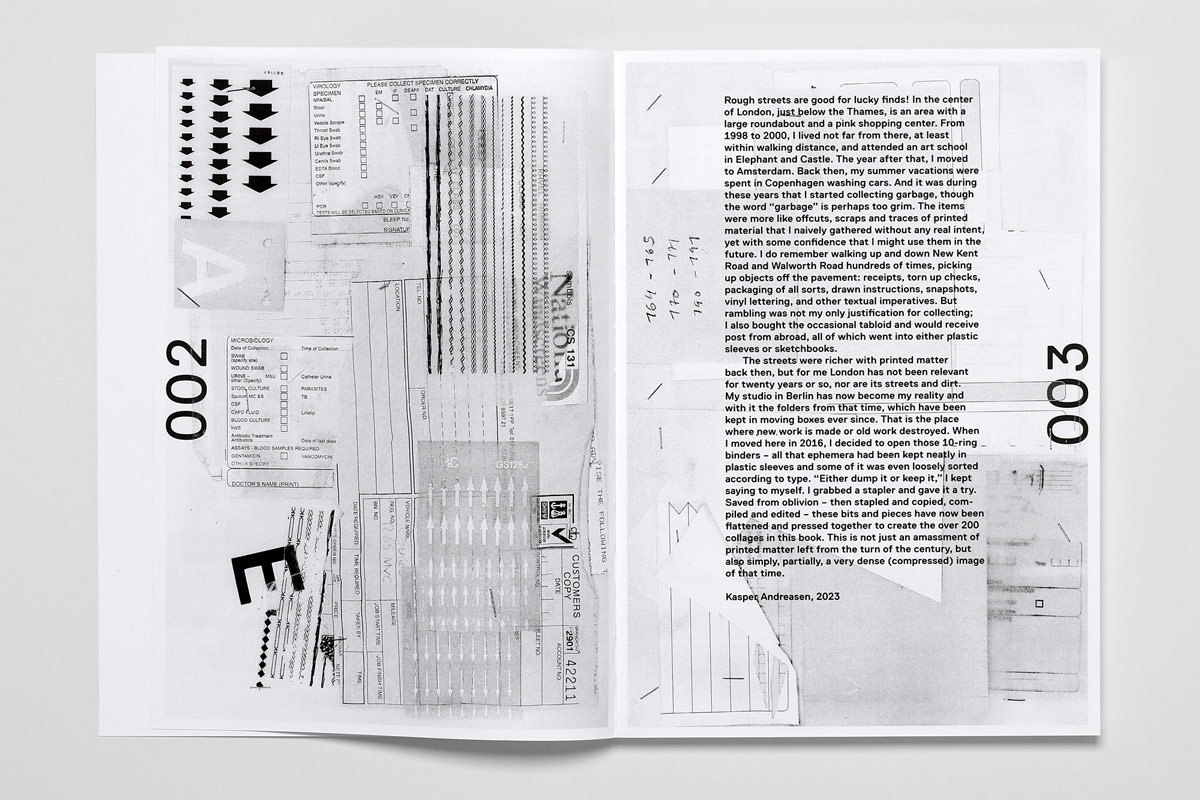

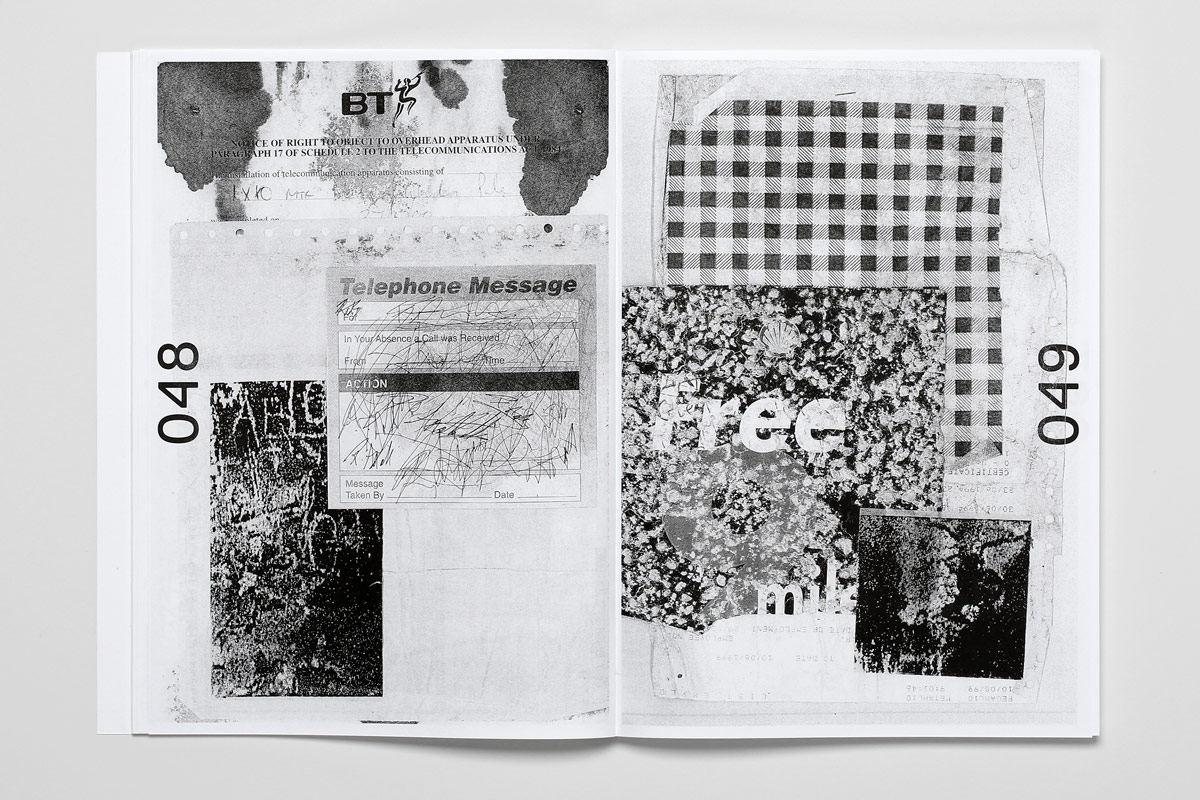

High Capacity generates an energizing tension between the subjective and the impersonal: this trash is supposed to be ‘our trash’ and so it feels strangely familiar and pretty alien alike. The specific blend of paper scraps we are talking about here mainly stems from North-Western ‘civilization’ around the year 2000. In other words, this ‘shit’ is made from our leftovers, the ones we were moving through every day, often without noticing consciously, and have not stopped to do ever since. Conversely, this ‘stuff’ has been selected, mixed, compiled by one person and the staples Andreasen used for his montages keep on appearing as rhythmic punctuations. Andreasen thus speaks and acts as an individual ‘I’, dealing nonetheless with ‘our’ collective material, that of us all, of no-one, of no body in the end; obviously, stuff people wanted to litter, or did not truly mind having lost or letting go off. Many scraps of user manuals, product announcements, public warnings etcetera constitute High Capacity’s image-text material. Hence, one can flip and skim, or even progress page after page, and ‘glean’ all the different graphic and verbal elements to be found and experienced. High Capacity is not to be read ‘globally’, as specialists of reading activities put it. More precisely, it is only to be read by adding and combining different ‘local’ interpretations one can make every time one enters this book and visits the various ‘spots’ this folded cartography has to offer. In this case, this kind of jumpy visual reading almost becomes an abstract form of catastrophe tourism; one can swiftly move from spot to spot and stare at endless variations of printed waste stemming from various industries.

Halfway the book, you encounter a big warning sign stating: NO RUBBISH TO BE DUMPED IN THIS PASSAGE (p. 102). Wherever Andreasen picked up this scrap, it takes quite a different meaning in this graphic narrative since nonetheless rubbish has been (securely) dumped by the recycling author! As a graphic artist Andreasen has not only specialized in the flip-through logics of contemporary art (copy) books – see for instance his project titled FLIP (2018) – but also researched the many overlaps between writing, drawing, landscaping and cartography. Publishing a fine compilation of printed waste matter adds to this researched link between image books and our physical surroundings in a surprising way. Andreasen often focuses on the manual acts leading to graphic utterances that are all too conveniently allocated to separate cultural domains, such as art, infographics, comics and literature. Products and artefacts in these divided cultural categories nonetheless share strong material resemblances, also resulting from the same or very similar graphic gestures and attitudes, e.g. tracing, scratching, registering. In this case, it is not so much tracing but hoarding and reassembling marked and printed objects (often cardboard and paper) that lead to a book on our (past) surroundings. Or to quote the author in the introduction: “Rough streets are good for lucky finds!” This strongly expressed tension between fine arts and the world of popular print objects of modern mass society is a recurrent aspect of Andreasen’s work, see e.g. recently Meta-LAT or Border Crossing. It is also in line with a (post)modern tradition of graphic production strategies and recycling approaches within fine arts, well exemplified by Hans-Peter Feldmann, Anne-Mie Van Kerckhoven, and Willem Oorebeek. High Capacity is thus to be visited in that sense, i.e. as a chrono-topical mapping of late postmodern society, a fragmentary attempt at mapmaking by a stray child of its time.

Pour your garbage down on me

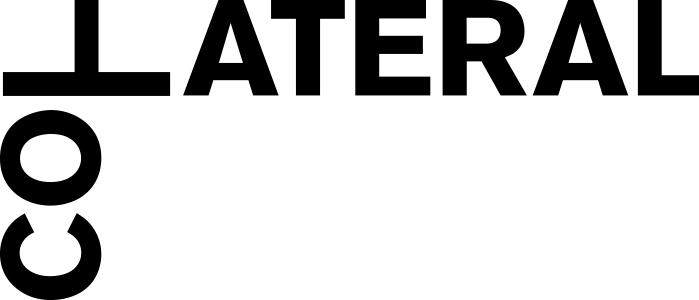

High Capacity starts in medias res, as the cover is already one of the about 200 collages Andreasen made for this publication. While the back cover only leaves “Snokey” to be read in Roman alphabet, and a shape which might be interpreted as an L, the front cover shows “ES1606”, “TIBBETTS_15”, “Telephone”, “01/10”, “Taken by Emily” – and the super-impressed title “HIGH CAPACITY”. Seemingly, reading at the dawn of the twenty-first century has become – decades before Elon Musk named his child after an impossible number code – an ever more estranging mix of everyday and specialized words and signs that make more or less sense. One has to decipher them and feels most often frustrated, only partly because of one’s ever limited knowledge, literacy and reading skills. Indeed, one can only read and understand that much, only ‘digest’ what one can grasp, the ‘rest’ is to be taken and accepted as such. And thus, it will keep on troubling you, including its verbal unreadability. Following this, one can only aesthetically deal with such literal nonsense. It is then through a more automatic, sensual, even zombielike wondering that one ‘reads’.

Such an approach to reading and collecting – etymologically akin – became Andreasen’s specialty, possibly starting from a subjective necessity to do so: “Back then, my summer vacations were spent in Copenhagen washing cars. And it was during these years that I started collecting garbage, though the word ‘garbage’ is too grim.” (By the way, Garbage was a popular Britpop post-punk band at the time: “Poor your misery down on me – I’m only happy when it rains.”) As a subject that grew up in the same period, only some years younger, I can easily relate to this: from my childhood years onwards I drifted on the beach, through the dunes and empty ‘city’ streets, half of the time picking up fascinating stuff my mother would declare to be “garbage” when I brought it home. Not only had I saved my cherished darlings – all kinds of small litter – from the erosive streets, beaches and wastelands but doing so I had retrieved them from the semiotic chaos of the world, that ever-growing vortex of nonsense which finally led to our contemporary situation of multiple realities, fake news, etc. Funny to think of young Andreasen picking up dirty cardboard packages at exact the same time, right across the Channel, in a ‘real’ big city such as London. And so did many others in those years, in an attempt of making sense of it all through a more physical form of collecting and compiling, while so many others in other places in the world were massively littering or having to work on that litter, none of them truly being busy with understanding that trash or even having the time for it. Speaking of cities, the title High Capacity not only literally refers to a snippet from toner packaging (to be found on page 149), “referring to maximizing the number of pages one can print from a single toner cartridge”, as Andreasen informed us kindly before publishing this text: “Additionally, the root word ‘city’ in Capacity directly alludes to the concept of an all-encompassing city.” Which city that specifically is or might be is for the reader-viewer to imagine, I suppose, keeping in mind that in our accelerated and intensly interlinked metamodernity cities worldwide indeed tend to blend into one overarching hyper-City. In that sense, High Capacity also shows us the traces of various global, mostly urban phenomena from around the 2000s.

How to read the world

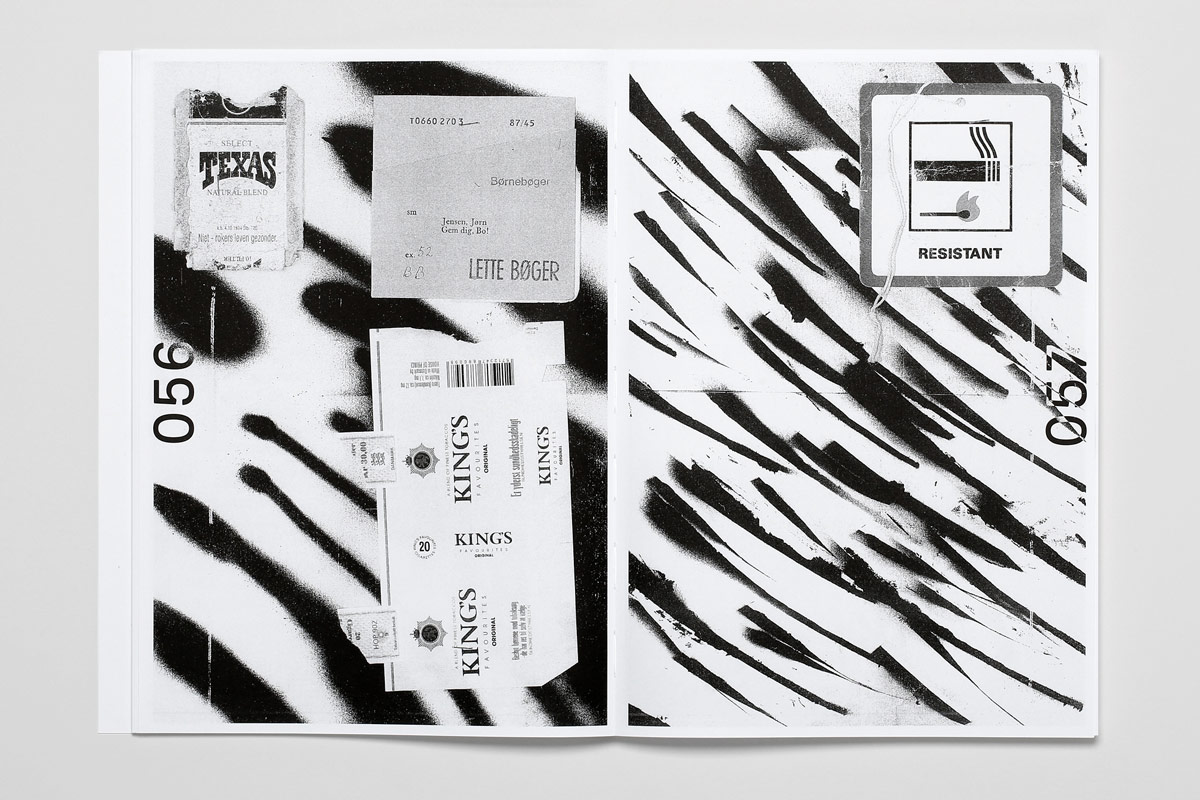

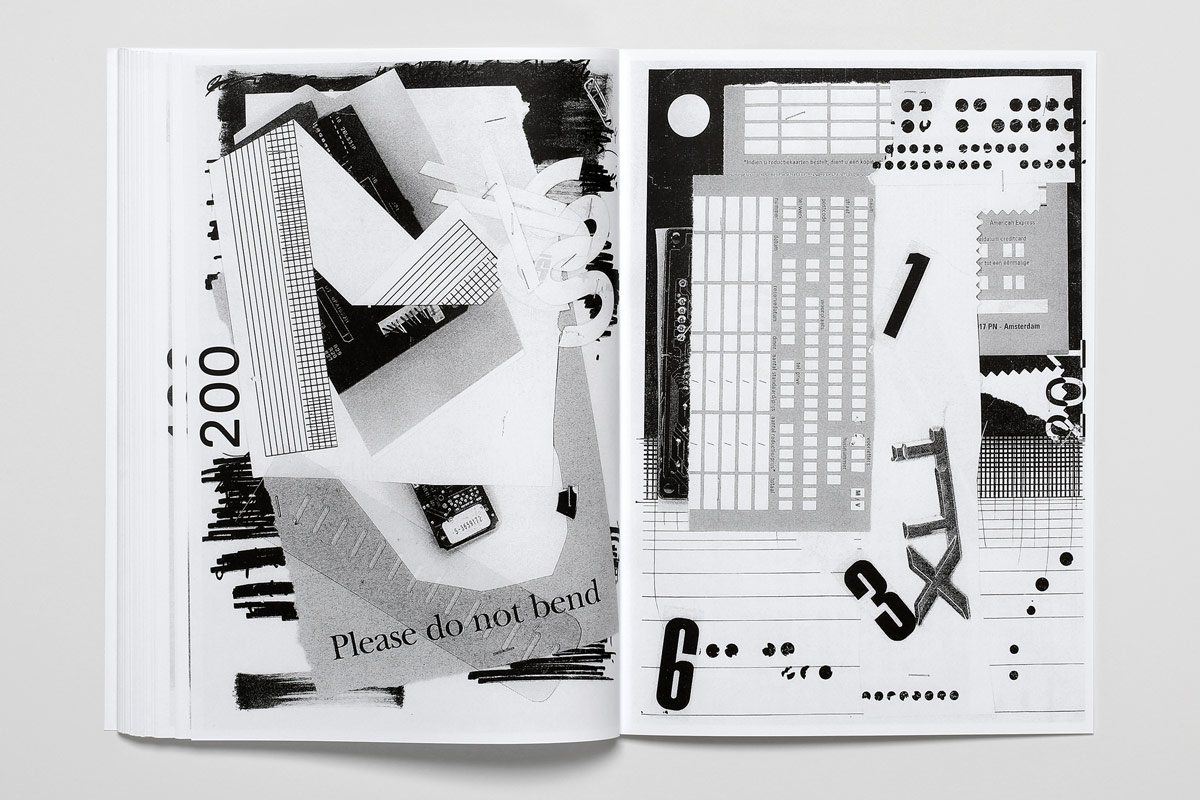

Obviously, this kind of re-editing of refuse is almost pre-archaeological work. If within fifty years, one wants to get a first, decent grasp of the latest ‘turn of the century’, not only skimming through but truly reading, studying, and analyzing Andreasen’s High Capacity would be a perfect start. But the publication is also a reflective retrospect in itself, since it focuses on stuff from the late 1990s and early 2000s but mixes them only twenty-five years later. As an artist’s book it stores the traces of the millennial turn but as a publication it also bears the mark of the kind of books we make today, continuing a broader tradition that started with DADA and Kurt Schwitter’s Merz-collages, passes the manifold recuperations by artists like Dieter Roth, runs over scrap books and DIY copy zines to all kinds of fully automated print-on-demand and other ‘impersonal’ literary productions. The manuals, instructions and banal warnings High Capacity richly consists of, are themselves the kind of uncreative texts put together by uninterested copyrighters and machines. What do these ‘texts’ even intend to say? Most of the time: don’t read this unless you’re a neurotic twat, scary of life’s inherent risks and liabilities, or some delusional freak who reads EVERYTHING. Here’s an overview of some snippets one gets to read when going through High Capacity: “onions (1), peppers (2), fish, white, chicken breast” or “T0660 2703 (staple) 87/45 Børnebøger sm Jensen, Jørn Gem dig, Bo! ex.52 BB LETTE BØGER” and “Select Texas Natural Blend k.b. 4.10.1994 Stb. 720 Niet – rokers leven gezonder. 10 Filter (upside down)”, “Penalty notice”, “Please read carefully the following before displaying lighters”, “Maximum safety”, “Reminder notice”, “See overleaf for details of how to pay”, “Do not stand on carton”, “Priority handling”, and so on. As a multiple radiography of late-nineties Western consumer societies, High Capacity would be worth a more in-depth analysis by linguists, sociologists and their analytic tools, such as automated computer text categorization. But what is immediately striking when reading this artist’s book is that the many image-texts that accompany massified consumption frequently go together with strong injunctions to do this or that or behave this or that way, or outright orders to execute or go along. The whole apparatus that is supposed to let us consume, enjoy, be entertained, relax, make use of practical and comfortable stuff, in short, ease and even better our lives, is an utterly constraining one, not only forcing us to deal with sometimes very cryptic or nonsensical sentences, schemes and illustrations, but also bombarding us with so-called ‘secondary’, disposable print matter that nonetheless constantly tells us what to do, how and who to be, literally in-forming us into overreactive consumer bodies.

High-speed time travelling

This constant disciplinary power also goes way beyond the verbally understandable and the figurative. This whole apparatus acts on the very level of its most often impoverishing designs (straight lines, hard edges, aggressive fonts), its vernacular and outrageously obscene photography, its silly infographics, its poor materiality. High Capacity intentionally flattens a good deal of its base material, already very ‘flat’ in itself, metaphorically speaking of course, but also literally (cardboard, papers, stickers): rearranging and reprinting printed matter critically repeats platitude and conversely gives it (art) historical depth. Everything is stapled together, composed as such and then photocopied in black and white or more exactly scanned and printed in rough greyscales. Subsequently, High Capacity also explicitly disposes of ‘original’ colors and material volume or density. This artistic double flattening functions as a mise à distance: the reader has to fill in and ‘feel in’ the objectal aspects of rendered fragments, mostly paper and cardboard or plastic prints. To be even more precise and technical: Andreasen himself speaks of “third-generation reproduction”: scraps of mainly offset material have been collaged and then copied, whereupon they ended up in the offset print of the book. Hence, Andreasen presents this graphic stuff as a collection of traces rather than as carrier of information: all these flattened, consecutive photocopies of things that once were useful, informational, communicative, bold, colorful, convincing and so on, now strike us as dead, absent, ghostly, and severely clipped together. Though the reader can still ‘collect’ (i.e. read) a load of significations from the many fragments put together, what prevails is the concrete, blunt deadness of all this ‘shit’. In other words, it is the stuff ‘itself’ but now looking like a cheap copy of the ‘original’ (often prints and hence ‘copies’ themselves) that emerges from this artistic montage. A clear example is to be found on page 057: a bunch of more or less parallel linear marks, probably spray-painted on who knows what kind of ‘original’ support. In the right corner, over some of these diagonal traces, a square sticker or cardboard showing the icon of a burning cigarette and a lit match underneath, followed by the word ‘RESISTANT’. A small cord running through a punch-hole at the top of the square and safely scanned with the rest indicates that the square has been added by the artist on top of the background with the spray-marks. Many interpretations of this specific montage are possible, also as part of the whole book and project. But more crucial is the material veracity, the graphic directness that such graphic work proposes; in the end, beyond all readings, that stuff subsists and does not let itself be decoded, since it eventually stays hors-code...

High Capacity is a collection of residues or leftovers, inevitably gone and only ‘saved’ through Andreasen’s peculiar art writing. His artistic intervention does not just consist of ‘collages’, though that is what the ‘original’ artworks that allowed the reproduced plates are – ‘agrafages’ would be a more fitting neologism. The list of ‘titles’ that Kasper Andreasen offers at the end of the book, baptizing each single page following a textual element appearing on the page, gives an insight in the preferences of the collector-sampler of this book, i.e. the author. Of course, they are the titles of the factual assemblages each book page is a scan of (since these works do continue to exist ‘outside’ the artist’s book), but they also function as a compact summary of what the reader might have ‘been’ through. For example, a short excerpt from the index reads as follows: “110 FORCED LANDING ON WATER 111 DO NOT REMOVE FROM THE AIRCRAFT 112 KRONDIAMANT-BRYLLUP (SAPPHIRE WEDDING ANNIVERSARY) 113 VI ER BLEVET GIFT (WE GOT MARRIED)”. Clearly, High Capacity not only works as a historical time capsule – of interest for historical economy, sociology, cultural studies and so on – but also as an explicitly jumpy hypertext, triggering the reader’s imagination and flashing them from one place of modernity to the other, from one trashy situation to the next. In the excerpt above one is ‘beamed’ from a forced landing on water to some Sapphire Wedding Anniversary (what or whoever that is), mentioning “We Got Married”. As with the corpus, you can just flip or browse through the index and likewise get an overall, non-linear impression of everyday scenes and themes from the end of last century. As a work of art and a work of literature, Kasper Andreasen’s High Capacity provokes another kind of viewer-reader: one that has to act as a deep diver and a scavenger at once, a hoarder and a litterer, invested and at distance, in retrospect, always imagining and re-actualizing what they might or might not have known or experienced in an ever more uncertain past. Of course, this odd rear-view mirror might be scary when thinking of our present, even more saturated by endless data streams of coercive nonsense, or the possible futures in the wake of this all. In other words, we are invited here to navigate as some kind of virtual time travelers.