35 — November 2022

clustered | unclusteredRADICAL MURMUR

A Sonic Exploration in Three Parts

The urban environment is generally captured in images and words. Researchers have a vast arsenal of visual means at their disposal to analyse and represent urban spaces and buildings, from photography to maps, floor plans, cross sections, elevations and drawings. Social scientists describe space and the interactions that take place within it. However, the sonic dimension – how an environment sounds – is usually left out of consideration.

TRASHLINIE is the heading under which we, a sound artist/radio maker and an architectural historian/publicist, have been making podcasts and audio projects since 2019. With TRASHLINIE we are interested in evoking a sense of space through sound. Interviews are typically conducted on location; this means that street noise and spontaneous encounters are included in the montage. The soundscape of any street can reveal a lot about the acoustic dimensions and atmosphere of a place, and even abstract and gradually unfolding processes like gentrification, segregation or ecological degradation can be audible, or at least have an effect on the sound profile of a place.

There is no fixed TRASHLINIE ‘modus operandi’ that has come about very deliberately. Rather, we found a shared curiosity in soundscapes at the intersection of our different areas of interest. The project RADICAL MURMUR has been a vehicle for us to deepen our own understanding of what we intuitively already found so interesting about working with ambient background hums, unintelligible murmurs, the sound of cars honking, snippets of conversations from people passing by, echos reverberating between buildings, the steady and slightly unsettling drone of a distant pile driver hammering away, and so on. Is this an aesthetic preoccupation, a kind of fetishization of raw noise as a marker of ‘street cred’, or do we really believe that sound, no matter how ugly or amorphous, contains information that is not transferable in words and images?

RADICAL MURMUR consists of three episodes. In this triptych, we meet a diverse and international cast of thinkers, artists and composers who, in very different ways, are thinking about the implications of making sound, recording sound and listening to sound. The fact that we group them together in this triptych does not mean that there is a clear interrelatedness or shared intellectual canopy. In editing, we tried to do justice to the tone, nuances and ambiguities of their individual practices. The interviews are also interspersed with excerpts from sound works or read-out passages from texts, to add to the overall ‘sound image’ of their work. Yet there are topics that keep recurring, that were, as it were, threaded through the conversations, such as the relationship between sound and power, the unrefined journalistic potential of sound, the minor space for sound in the European philosophical tradition, and the erosion of polyphony and sonic pluralism because of ecological degradation, consumerism or state violence.

In addition to Collateral, we would like to thank the two other collaborative partners who made RADICAL MURMUR possible, namely rekto:verso and Gonzo (circus). Regardless of whether the end result is satisfactory – you will have to listen to judge that – it speaks well for these media that they supported a project with the unpitchable premise of a three-hour ‘exploration of sound’. We would also like to thank the interviewees for sharing with us the richness and multiplicity of their work. The interviewees are, in alphabetical order: Justin Bennett, Evelien van den Broek, Peter Cusack, Mint Park, Davide Tidoni and Salomé Voegelin.

TRASHLINIE is Sjoerd Leijten and Roel Griffioen. RADICAL MURMUR was made in collaboration with rekto:verso, Gonzo (circus) and Collateral.

a

clustered | unclusteredEpisode 1

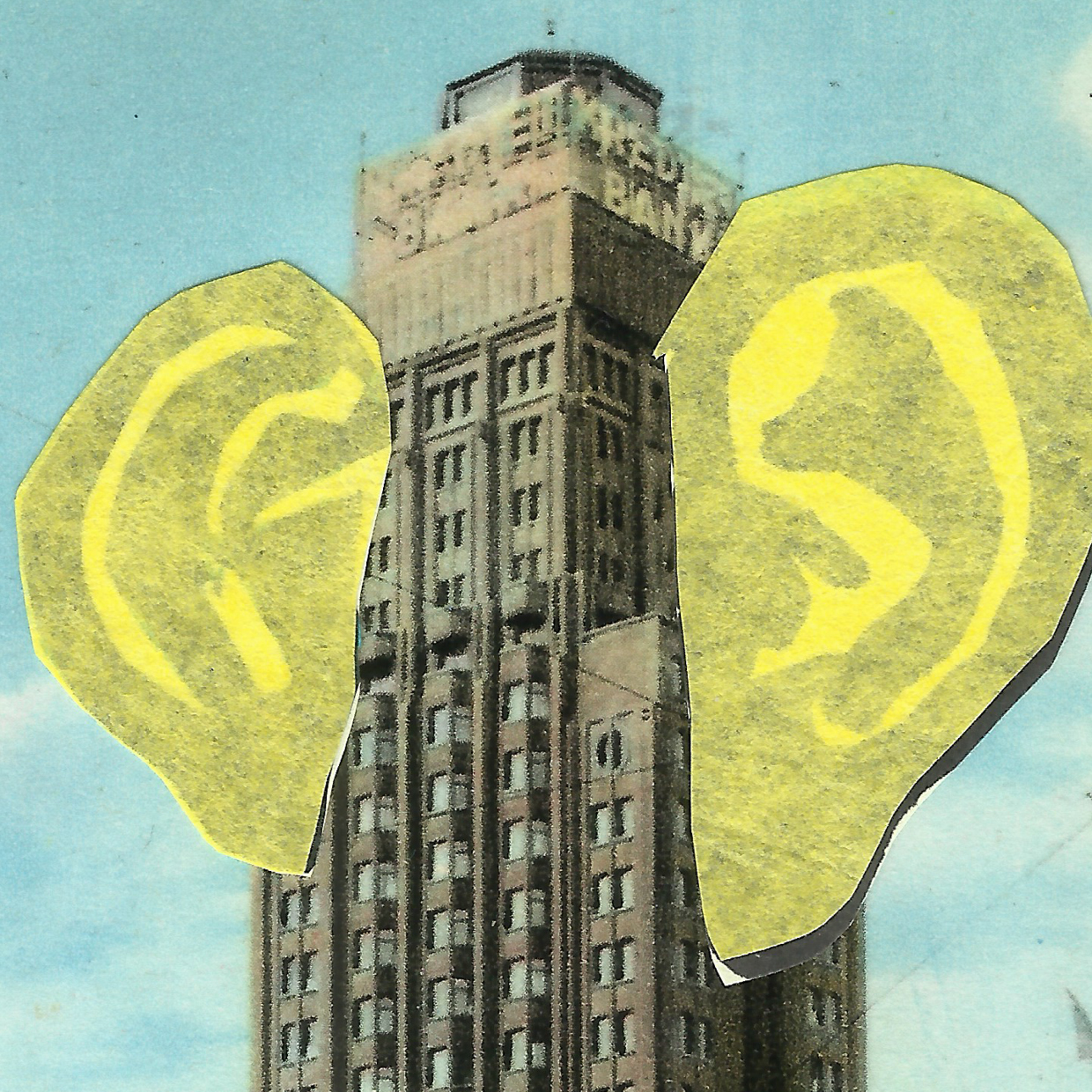

The Sonic City

In this episode, we listen to the bustling hum of human activity, the reverberation of sounds between buildings and the familiar ring of the tram bell. What city sounds do we become attached to and why? How does sound help us navigate traffic, society and history? We climb a former Nazi bunker with sonic philosopher Salomé Voegelin, hear the squeaks and creaks of Berlin’s S-Bahn with artist and sound connoisseur Peter Cusack, and reflect on sonic utopias and ways to ‘read’ city sound with sound artist Justin Bennett in a shopping arcade in The Hague.

b

clustered | unclusteredEpisode 2

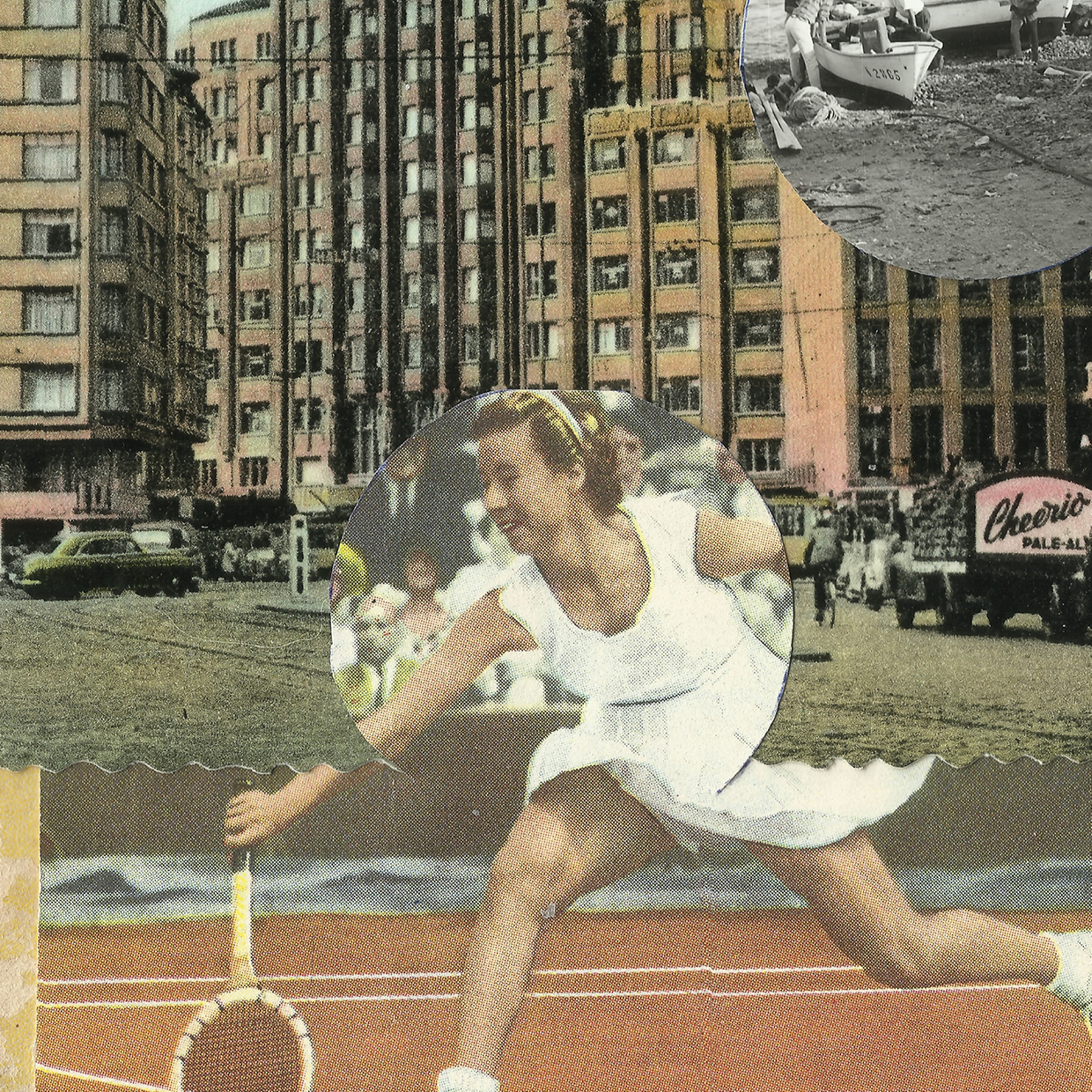

Resonances of Loss

In this episode, we listen to the sighing and groaning of a tired planet. In composer Evelien van den Broek’s music, we hear field recordings of animals that no longer exist. This is how she tries to make the current “biological destruction” palpable. Peter Cusack travelled to Chernobyl and other ecological disaster zones as a “sonic journalist”. What do places we know from the news but that we have never ‘heard’, sound like? And philosopher Salomé Voegelin reflects on how the COVID-19 crisis threw us back on ourselves, threatening to evaporate the sonic “in-between” between people. “There is no inner genius, there is only an outer connection.”

c

clustered | unclusteredEpisode 3

Reflections amidst the Noise

“Sound can get contagious and move from mouth to mouth, or from body to body.” In the third and final episode, we immerse ourselves in the remarkable sonic practices of two sound artists. On the Hembrug terrain in Zaandam, Mint Park takes us on a field recording session. Mint uses turbulence and field recordings to bring about a distinct non-human perspective. We also meet Davide Tidoni. His work involves flogging microphones and speakers, popping balloons and documenting the vocal culture of hooligans. In two languages, Davide provides a listening guide to his multifaceted work. What artistic and political potential is hidden in sound? An episode about risk, entropy, turbulence, contamination, control and chance.

d

clustered | unclusteredAppendix

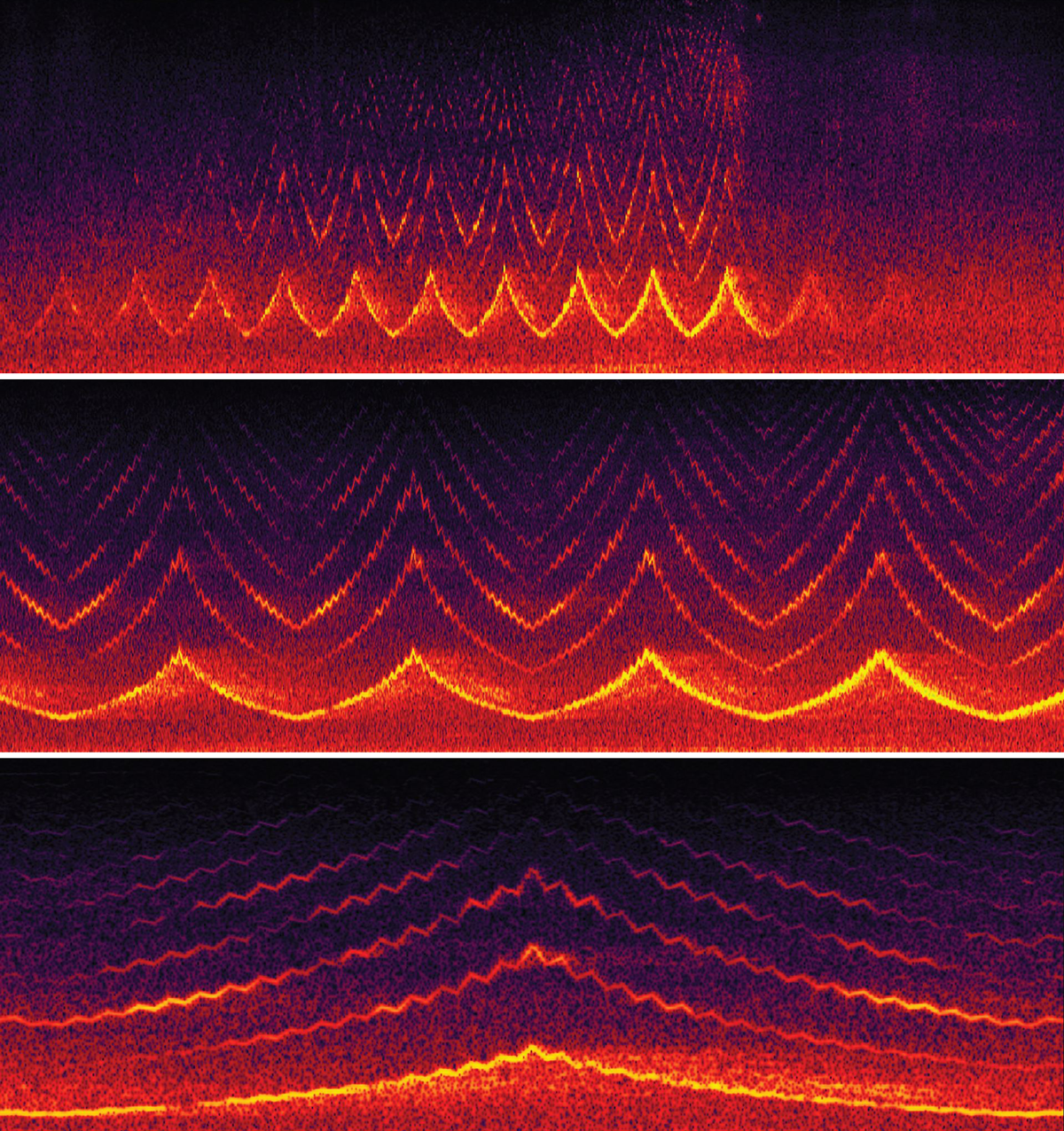

Justin Bennet — Siren Song

“The sirens fitted to the emergency vehicles in Brussels have always been clearly present in the sonic environment, but since the recent terrorist attacks their presence is almost ubiquitous.

Like the calls of a bird or other territorial animals the sirens proclaim: I am here. This (street) is mine. Of course this is exactly the intention — a proclamation of the ownership of, or the right to use, the roadway above any other user. In claiming the street though, they perform a double territorialization by also dominating a large portion of the sonic spectrum.

The sirens, especially those that sweep up and down in frequency, cover a large part of our functional hearing range, particularly that which we use for listening to speech. The sweeps start usually at about 500 - 600 Hz in order for them to be heard clearly above the rumble of traffic. The upper fundamental frequency is usually about 1500 Hz, but the harmonics of overtones, audible when in line-of-sight of the vehicle, go up to about 8000 Hz. The volume that the sirens produce — 100 dB (measured at 3.5 meters in front of the vehicle) — is apparently necessary to allow them to be heard over in-car sound-systems.”

Davide Tidoni — THE STADIUM AS I WANT IT

Salomé Voegelin — SoundWords

House Score 12

Lean against a wall Pretend you are a bookshelf Start reading anything Out loud

Dead kittens (for Mark Peter Wright)

Take a recording device Go outside and record with and without a windshield Listen to what is on top and underneath