23 – January 2020

clustered | unclusteredDutch Domestic Colonization: From Rural Idyll to Prison Museum1

Hanneke Stuit

- Paupers

- Colonists

- Patients

- Guards

- Inmates

- Refugees

- Collaborators

- Smugglers

- Prisoners

These are some of the denominations imprinted on inhabitants of the Colonies of Benevolence (Koloniën van Weldadigheid) over the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Conceived by colonial officer Johannes van den Bosch (1780-1844), the Colonies’ stated purpose was to address extreme levels of paucity in Dutch cities after the Napoleonic period. This was a charitable initiative that also addressed the moral, social, and political threat poor populations were thought to pose to the ruling elites. The plan ultimately led to the creation of several agrarian colonies in the rural Dutch province of Drenthe, which “was home to a number of largely subsistence-oriented farm communities organized as semi-feudal marke.”2 The colonies that would come to occupy the otherwise “unused” sandy and peaty wastelands of Drenthe were Frederiksoord (1818), De Ommerschans (1819), Wilhelminaoord (1820-1822), Willemsoord (1820-1823), and Veenhuizen (1823). Later, Colonies were also erected in the Southern Netherlands, now Belgium, following the same model: Wortel in 1822 and Merksplas in 1825.3 These internal colonies were to provide livelihood, education, and moral uplifting for the urban poor, and to create additional food supplies for the rest of the country.4 The Colonies were supposed to be completely self-sustained within sixteen years of their inception in 1818,5 but it soon became clear that a large number of colonists were unable or did not want to work the land, that the soil was not suitable for large crops without the added structural costs of obtaining manure from elsewhere, and that management lacked the necessary agricultural experience.6 The Society of Benevolence could not shed its debts and the regime within the Colonies became grimmer.

Whereas people volunteered to join the first colony of Frederiksoord (even if it is debatable how “free” this choice really was), it did not take long for two penal colonies – de Ommerschans and Veenhuizen – to be erected. These were used to (temporarily) banish and discipline “bad” free colonists and to house orphans and vagrants from urban environments, who were denoted as “verpleegden” (patients) in need of help.7 In 1859, the Society transformed the former “free” colonies into large-scale farms, and the lands and estates of the penal colonies were transferred to the Crown.8 With this shift, the charitable aspects in Veenhuizen started to fall away.9 Housing refugees from the south of the Lowlands during the separation of Belgium from the Netherlands and the First World War, Veenhuizen became an increasingly carceral site during and after the Second World War, when its population was broadened from vagrants and beggars to include collaborators and smugglers. It developed into a closed prison village harboring not just prisoners, but also offering housing for prison guards and their families.

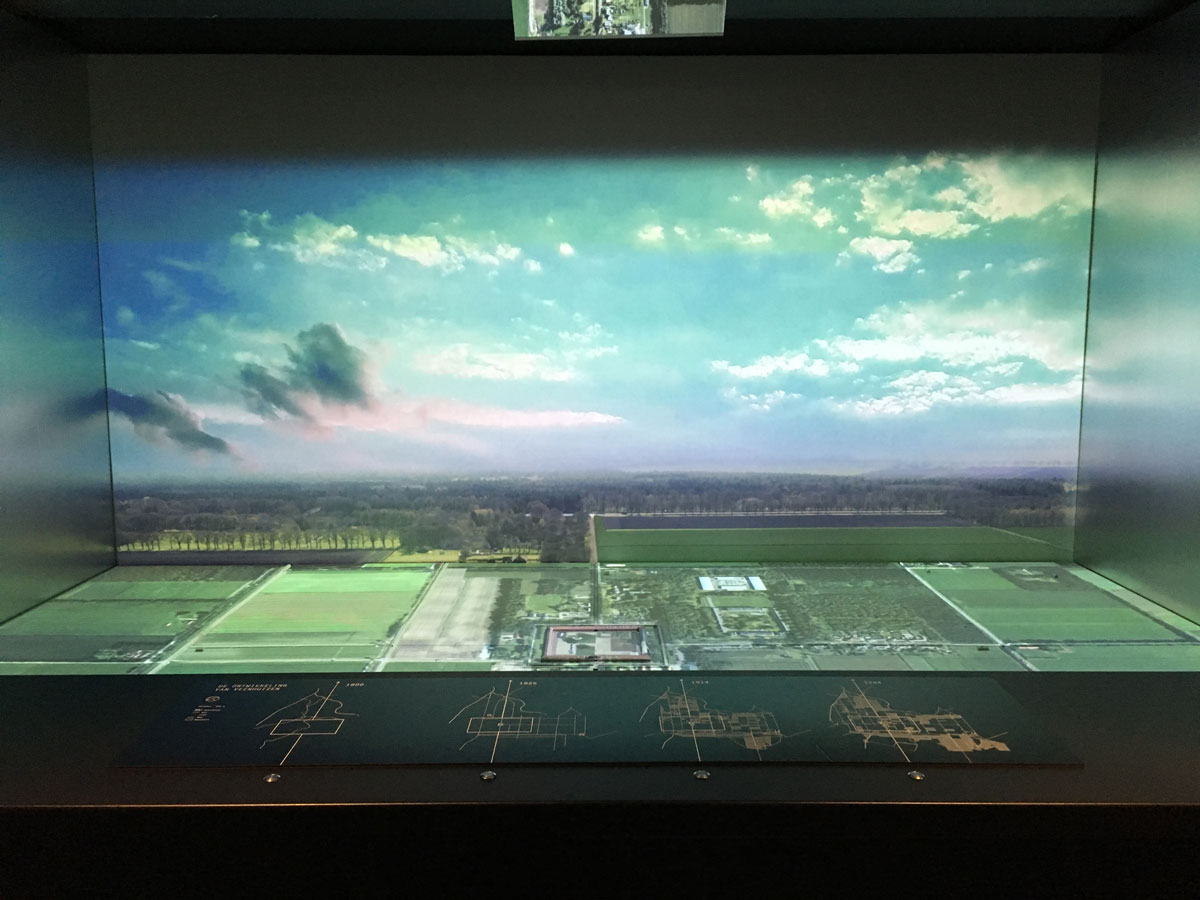

Nowadays, Veenhuizen contains no less than four prisons and an ammunition depot owned by the Ministry of Defense. Two of the prisons are still in function, the third is empty but ready for service, and the fourth was used to house refugees up until May 2018 but now stands unused. At the same time, the village is extensively marketed to tourists, and the Society of Benevolence, which still exists, is working on a bid for it to become a UNESCO world heritage site.10 Tourists can visit the National Prison Museum housed in one of the many surviving Colony buildings or take a guided tour of the village and the “stand-by” prison. Veenhuizen is also framed as the ideal gateway to the surrounding countryside. Yet, financial problems continue to threaten Veenhuizen’s future: about a third of its estates, now in possession of the Government Buildings Agency, are currently being put up for sale.11

This cluster is based on a trip to Veenhuizen in the context of the Rural Imaginations project, which focuses on “the crucial role played by cultural imaginations in determining what aspects of contemporary rural life do and do not become visible nationally and globally, which, in turn, affects how the rural can be mobilized politically.”12 The project is conducted at the University of Amsterdam and funded by the European Research Council. During the trip and the development of this cluster, it became increasingly clear that the rural plays an important part in the history of Veenhuizen and the other Colonies, up to the present day. Initially, the Colonies of Benevolence were purposefully located in the countryside because this setting was considered beneficial to the moral uplifting of the poor. The choice of the countryside, however, was not just inspired by the idyllic paradigms of fresh air, inspiration, and exercise commonly projected on the rural. Instead, the notion of agricultural labor was central to the Christian-cum-Enlightenment thought on which the Colonies were based (Bosma and Valdés Olmos). As a comparison between these Dutch internal colonies and Maoist initiatives of sending urban educated youth to the countryside in China clarifies, the imagined effects of agricultural labor were fundamental to the philosophical underpinnings of the Society’s liberal discourses of subjectivity (Ng). In other words, this social experiment was intended to produce a laboring population that could unite the Lowlands economically and would allow it to enter the Modern era.13

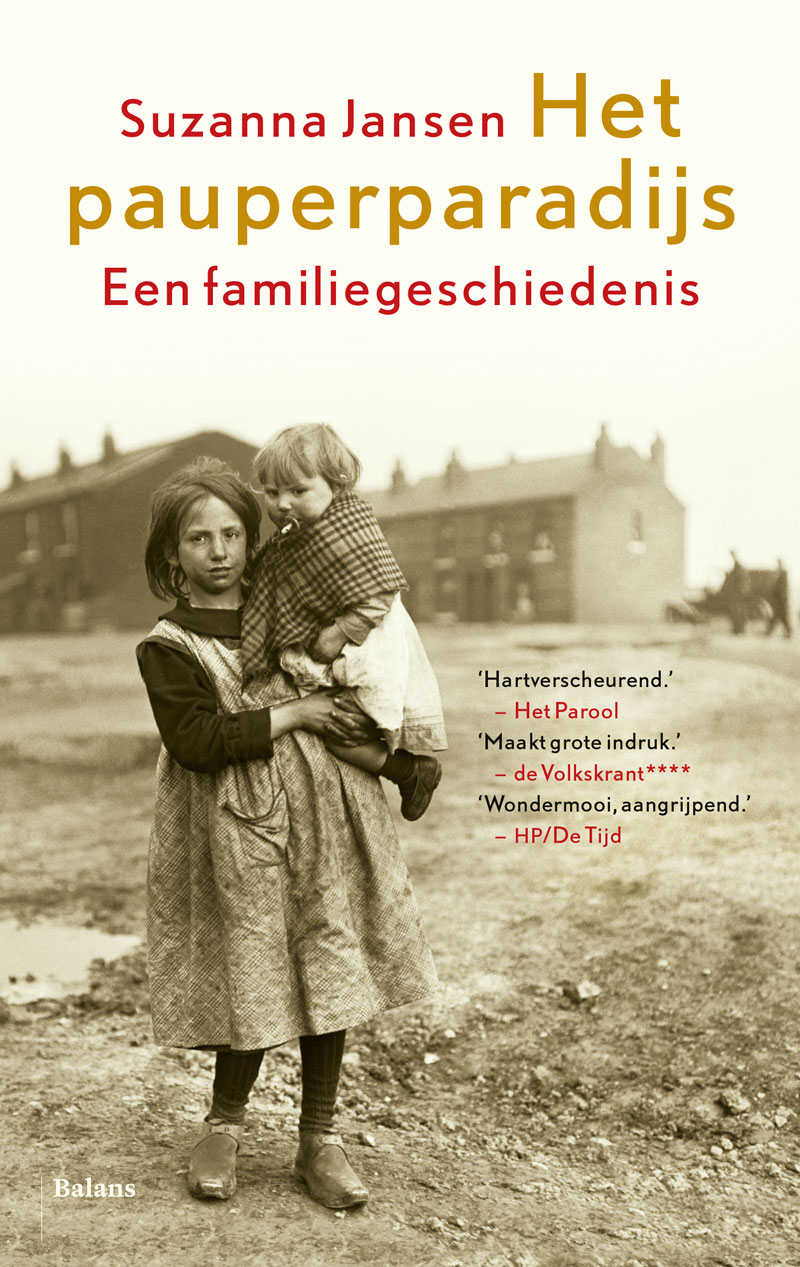

At the same time, however, the persistence of the idea of the countryside as pleasant and wholesome allows for the specificities of colonization and oppression in Veenhuizen and the other Colonies to remain unnoticed. From the visual material available on the Colonies, it becomes clear that rural idylls operated in conjunction with “carceral idylls,” which naturalized the displacement of considerable parts of the population to the edges of the Dutch Kingdom in the name of moral improvement (Stuit). Even though about a million Belgian and Dutch people can trace their lineage to the Colonies14 and despite the popularity of Suzanna Jansen’s seminal work on Veenhuizen (Het pauperparadijs, 2008), in which subpar living conditions in Veenhuizen are amply discussed,15 little debate in the public sphere focuses on the problematic aspects of the Colonies’ heritage, or on its ties with Dutch colonization abroad. Rather than commemorating colonial subjects or engaging with the issue of lineage critically, finding out about one’s ancestors there is now an integral part of the marketing of the Colonies as a tourist destination.16 In the touristic exploitation of Veenhuizen, especially in the National Prison Museum’s gift shop, it becomes clear that decontextualized and nationalistic notions of the rural render invisible these histories of colonial oppression, both in a national and international context (Peeren).

We ask, therefore, how current uses of the Colonies in general, and Veenhuizen in particular, seem to gloss over the ways in which the carceral, the rural and the colonial intersect. How do these uses obscure the Colonies’ uncomfortable connections to Dutch colonization in the East and West Indies? Which views of Veenhuizen are actively pursued and sanctioned, and which are disavowed? In order to explore these connections and questions, this cluster brings together close readings of contemporary elements of Veenhuizen, the historical context of the Colonies of Benevolence, and its resonance with other contexts that pertain to the colonial, the agricultural, and the carceral. As these joint contributions show, imaginations of the rural offer an idealized setting for lofty ideals and spectacularized consumption that render the rural invisible as a situated territory traversed by various structures of power and control.

Notes

- 1This publication emerged from the project ‘Imagining the Rural in a Globalizing World’ (RURALIMAGINATIONS, 2018–2023). This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (grant agreement No. 772436).

- 2Albert Schrauwers, “The ‘Benevolent’ Colonies of Johannes van den Bosch: Continuities in the Administration of Poverty in the Netherlands and Indonesia,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 43.2 (2001): 308-309,

- 3See the Koloniën van Weldadigheid website.

- 4Schrauwers, “The ‘Benevolent’ Colonies,” 316.

- 5Wil Schackmann, De strafkolonie. Verzedelijken en beschaven in de Koloniën van Weldadigheid, 1818-1859 (Amsterdam: Atlas Contact, 2018), 15.

- 6The Colonies of Benevolence: An Exceptional Experiment, ed. De Clercq, Van den Broek, Van Nieuwpoort and Albers (Assen: Royal Van Gorcum Publishers, 2018), 33.

- 7Schackmann, De strafkolonie, 19-20.

- 8Koloniën van Weldadigheid website.

- 9Suzanna Jansen, Het pauperparadijs. Een familiegeschiedenis (Amsterdam: Uitgeverij Balans, 2008), 107.

- 10A new submission is currently being prepared after feedback from the ICOMOS (the UNESCO advisory committee). The bid is expected to be filed by the Dutch and Belgian governments in January 2020, and a decision is expected in the summer of 2020. The four visitor centers in Merksplas, Ommerschans, Frederiksoord and Veenhuizen have also submitted a joint request for a European Heritage Label. Koloniën van Weldadigheid, “Bericht aanpassing Nominatiedossier,” 10 September 2019.

- 11Jurre van den Berg, “Te koop: gevangenisdorp Veenhuizen t.e.a.b.,” De Volkskrant, 28 August 2019.

- 12Esther Peeren, “Rural Imaginations Project Description,” (2019).

- 13Schrauwers, “The ‘Benevolent’ Colonies.”

- 14Koloniën van Weldadigheid website.

- 15Jansen, Pauperparadijs, 104-105.

- 16See the Koloniën van Weldadigheid website, the tourism website for Drenthe, or Allekolonisten.nl.

a

clustered | unclusteredThe Coloniality of Benevolence1

Anke Bosma and Tjalling Valdés Olmos

What might it mean to approach Veenhuizen as a node in the Dutch imperial project? Most of the historical and cultural framing around the Colonies of Benevolence has followed a teleological vision – moving from a failed but well-intended philanthropic project of poverty control to a well-functioning neoliberal welfare state.2 This approach has overlooked the Colonies of Benevolence as a nexus of ideas and histories legible under the ongoing logics of modernity/coloniality.3 This concept, first coined by Aníbal Quijano, refers to the manner in which modernity and coloniality are inseparable yet different aspects in shaping both historical and contemporary social orders and modes of knowledge production.

In the following article we want to emphasize the foundational importance of this modernity/coloniality nexus to understanding the historical and ongoing development of the Dutch neoliberal state. Or, in Gloria Wekker’s words, we want to highlight the “centrality of imperialism”4 to Dutch culture by looking at the Colonies of Benevolence through a (de)colonial lens. In most mainstream and institutional narratives, like the ones used at the National Prison Museum in Veenhuizen (see Peeren, this cluster), the Colonies of Benevolence are predominantly explored from a historical perspective in which the “history of the metropole is structurally seen apart from the history of the colonies.”5 Veenhuizen is considered in the context of national and European Enlightenment history, while its founder Johannes van den Bosch’s enterprises in the Dutch East Indies are seen as colonial or imperial history. The constructed distinction between these histories obfuscates that populations in both locales were (and are) connected by a colonial archive. This connection is exemplified by different forms of violent oppression and exploitation experienced under a shared logic and praxis of modernity/coloniality that is always already “unevenly distributed” in degrees of “unfreedom” across the globe.6

In the first section of this contribution we highlight the Christian-cum-Enlightenment characteristics of the imperial project that constituted the Colonies of Benevolence. We do so by emphasizing Johannes van den Bosch’s role as an imperial agent who moved within and across global circuits of colonial-capitalist knowledge production.7 The Christian and Enlightenment ideals that were central to his colonial endeavors and essential to modernity/coloniality in general served as an important justification for the exploitation of people in the Netherlands and the former Indies and their construction as potentially improvable “idle paupers.” In the second section, we turn towards this modern/colonial revalorization of people (and land), and question its relation to historical and contemporary forms of urban planning and social housing in the Netherlands, taking Suzanna Jansen’s memoir Het pauperparadijs (Paradise of Paupers) (2008) as a point of departure. We pose that the logics of modernity/coloniality, in its intertwinement with Christian-cum-Enlightenment knowledges, shape both historical and contemporary technologies of social and spatial control directed towards criminalized and racialized working-class subjects.

Idle Subjects in Van den Bosch’s Colonies

In both popular and institutional discourses – such as the UNESCO heritage application, the official prison museum booklet (based on the UNESCO application), and the 2018 Dutch public television documentary “Land zonder paupers” – Van den Bosch is often portrayed as a visionary: someone with good intentions, admirable ideals, and a strong will, whose efforts failed because of unfortunate circumstances.8 Special attention is given to the benevolent nature of his ideas, which are broadly based on Christian and Enlightenment notions of humanity and deemed admirable because of their charitable framing with regard to poor and working-class people. Nevertheless, we can ask how benevolent these ideas actually are. Christian-cum-Enlightenment thinking formed an important part of the ideological weave of modernity/coloniality, especially with regard to legitimizing the exploitation and oppression (racially, classed, gendered, etc.) of “othered” populations and the violent altering of ecological and natural landscapes. 9 For example, western hemispheric colonial plantations involved the capture and dehumanization of Africans and “agricultural landscape simplification” that resulted in the homogenization and radical reduction of diverse aboriginal vegetation, local agricultural practices, and wildlife.10

The extensive colonial career of Van den Bosch started in 1798 with a military position in Indonesia, a colony known as the Dutch East Indies at the time. During his first stay in the Dutch East Indies, Van den Bosch had indigenous populations, which he considered to have previously “spent their time badly,” work a plot of land he owned, and eventually sold the plot for eight times its original price.11 He cites this colonial-capitalist exploitation in his plans for the Colonies of Benevolence, which he founded some years after his return to the Netherlands. From 1827 to 1828, he was the commissary general of the West Indies, a territory that included what is now Surinam, Aruba, Curaçao, Saba, St. Eustatius, and St. Maarten. He was appointed governor-general upon his return to Indonesia in 1830. In 1834, he went back to the Netherlands, where he soon became Minister of Colonies.12 Across all these locations, his ideas and practices regarding the management of indigenous populations, paupers, and unworked land traveled with him. As Ann Laura Stoler has shown, Van den Bosch was linked to an expansive network of other colonial and penal governors, reformists, thinkers, and institutions that stretched across the imperial globe.13

Van den Bosch started the Colonies of Benevolence in the Netherlands because he believed that paupers needed to be uplifted and saved from their vices and idleness for the benefit of society as a whole. With European colonial expansion and the project of Dutch capitalist nation-building after the Napoleonic wars well under way, earlier Christian and Enlightenment ideas regarding human differences were “intensified, expanded, and reworked.”14 Van den Bosch thought his project would ameliorate the perceived threat of contamination and miscegenation that these populations were seen to pose to the rapidly urbanizing centers of European civilization.15 Nineteenth-century ideas on miscegenation and contamination were heavily influenced by colonial endeavors across continents, especially with regard to non-white populations.16 Many members of the elite classes, like Van den Bosch, considered the potential spread of poverty, and its associated notions of vice and idleness, a threat to public order. Safeguarding this order, however, did not just mean preventing violence or crime. Given the reasonably recent events of the French Revolution, it quite specifically meant maintaining the social order by protecting the political and socioeconomic interests of the elites.17

The conflation of idleness with vice was due to the ideological construction of idleness. Within Christianity, particularly after the Reformation, work was seen as the fundamental divine edict. One had to work to atone for Adam’s fall. Agriculture, the main form of labor in the Colonies of Benevolence, is specifically important to Adam’s fall because, in Genesis, God condemns Adam to it: “cursed is the ground for thy sake; in sorrow shalt thou eat of it all the days of thy life.”18 The earthly ground would be intentionally tough to grow crops on and thus would require hard work, in contrast to the effortless abundance of the garden of Eden. To work, then, in the Bible quite specifically means to till the soil. However, within Christian ideology after the reformation this was interpreted more broadly: it was sinful to live off what nature provides rather than producing food by tilling the soil; living on charity was considered similarly sinful. Within Enlightenment thinking, the Christian discourse around idleness largely remained, but replaced a man’s duty to God with a duty to himself: only through work could a person improve themselves and be uplifted.19 As a result, not working was seen as leading to one’s deterioration as a person. “Rust roest” (“rest makes you rust”), one of the mottos of the Colonies of Benevolence, exemplifies this idea. As a Christian who was also invested in the developing industrial and capitalist nation, Van den Bosch felt the Colonies of Benevolence would allow people to reach their full potential through selling their labor in a capitalist system.20

.jpg)

The emerging views on the use of people as capitalist subjects – weaved together with Christian-cum-Enlightenment discourses – were tested in overseas colonial projects. As mentioned above, the interior colonies of Drenthe were partially based on Van den Bosch’s earlier endeavors in the Dutch Indies. Later on, after the collapse of the Dutch East India Company, the Dutch considered making money in Indonesia by trading with the local people, but ran into a problem: the local people “had very little needs.”21 They were content with what they had and did not need anything more, or at least not anything the Dutch could offer. Since Indonesia could not be made profitable through trade, the colonizers turned to forced labor, which was viewed as the only remaining option and considered controversial even among colonial officers.22 Forced labor was implemented through Van den Bosch’s Cultivation System, which forced peasants on large parts of Java, Sumatra, and Minahasa to cultivate cash crops like sugarcane, indigo, and coffee, and hand them over to the Dutch state. Implemented in 1830, this system was legitimized by the same discourses as the Colonies of Benevolence: making both land and people productive and valuable within the logic of capitalist (re)production.23 Besides causing human and material devastation, the Cultivation System also incorporated the indigenous populations and land of Indonesia into a globalized capitalist system based on the continuing logics of European modernity/coloniality and progress.

Thus, populations previously seen as unable or unwilling to contribute to the increasingly industrialized, colonially funded, capitalist, and hetero-patriarchally structured Dutch empire were subjected to certain regimes of disciplinary control that made it possible for them to be managed under a developing set of grammars regarding modern subjectivity. Even if initiatives like the Colonies of Benevolence naturalized some of these populations as potentially valuable (re)productive subjects, others remained undesirable, excluded, and marginalized.

The Continued Legacy of Undesirable Populations

In Het pauperparadijs (2008), Suzanna Jansen traces her family history from their arrival at the Colonies of Benevolence in the early nineteenth century. The novel highlights how thousands of paupers, including her ancestors, were put on trial for the crimes of “vagrancy” and “begging” and sent to the Colonies. Significantly, historian Wil Schackmann shows that this criminalized group of people were an elusive category. For example, more than 60 percent of the “vagrants” and “beggars” held in Veenhuizen and Ommerschans were people with physical and/or mental disabilities, elderly folk, and families without a male wage earner.24 The distant location of Drenthe, on the margins of Dutch society, served to maximize the spatial distance between these undesirable populations and idealized “proper” populations. In the Colonies themselves, moreover, internal distinctions were made between those populations that were seen as redeemable and those that were not. Het pauperparadijs sheds light on how the categorization of Jansen’s ancestors as belonging to this unredeemable criminalized population of Veenhuizen continues to haunt following generations.

Jansen’s grandmother Roza is one of the women for whom escaping the haunting legacy of the Colonies of Benevolence is impossible. When Roza moves to a convent, her admission to the convent is only possible by occluding her family background as it related to the Colonies of Benevolence.25 When Roza’s family history is revealed to the Mother Superior of the convent, she is dismissed and finds herself subjected to new forms of spatial displacement. Roza is, together with her husband and children, eventually housed in a new urban project: Tuindorp Oostzaan (Garden Village Oostzaan). Now, this area forms part of Amsterdam North, but at the time it was known as the Siberia of Amsterdam.26 Veenhuizen, similarly, was known as “Dutch Siberia”.27 Tuindorp Oostzaan and other neighborhoods like it, such as Floradorp and Asterdorp, were part of a new social experiment at the start of the twentieth century, reminiscent of the logic employed in the Colonies of Benevolence. In order to eradicate poverty, the criminalized poor were housed and “re-educated” there.28 In these villages, populations were under close surveillance and could move up on the social ladder through non-idle behavior, which would also allow them to move to a better (i.e. less supervised) village. Jansen poses that the municipal council was aware that those who came to be housed in this Siberia of Amsterdam would carry with them a “stigmatization” that would be hard to get rid of. Yet, the municipality also opined that this spatial “branding” would help fashion the criminalized poor into “more proper” citizens.29 Jansen’s use of the term “branding” posits the Colonies of Benevolence and the Tuindorp housing projects, both institutions of modern/colonial subjectification, as spaces that become imprinted on the flesh. This is a particularly poignant metaphor that emphasizes the interrelation between the discursive and material, and shows how sustained poverty and exclusion have lasting effects on multiple generations of human bodies.30

Jansen’s memoir offers an important intervention by showing how the colonial logics and practices of Veenhuizen do not belong to the past. The housing of less-than-human populations in zones removed from more valued national subjects connects the rural Colonies of Benevolence to the urban Garden Villages of Amsterdam North. Both operated under the Christian-cum-Enlightenment idea that labor could potentially cure the idleness and vices of such populations, and buttressed the colonial-capitalist need for an increasingly productive and manageable workforce. These days, such logics can still be partially found in contemporary urban realities. Neighborhoods such as Bos en Lommer, Nieuw-West, and Bijlmer in Amsterdam, as well as neighborhoods in other cities popularly known as Vogelaarwijken,31 continue the conflation of what are considered undesirable and threatening populations with spaces deemed uninhabitable for normative Dutch subjects.

Additionally, these urban spaces are often predominantly inhabited by racialized non-white others (populations marked by the longue durée of globalization and migration), which shows the penchant for colonial logics to stick to various bodies subjected to regimes of differentiation. Global forms of capitalist-induced precarity, however, have increasingly eroded both the possibility and the idea that such communities can attain normative subjectivity through productive labor. Furthermore, those who are presently framed as the Others of the Netherlands (predominantly populations with colonial and migrant histories spanning South America, the Caribbean, North Africa, and the Middle East) are seen to threaten, under the lingering logics of contamination and miscegenation, the white criminalized poor and working class people who once inhabited these selfsame national margins. At the same time, gentrification, or the “deconcentration of poverty,” is used to transform areas predominantly inhabited by non-normative subjects into livable spaces capable of attracting subjects that fit better with the image of Dutch normalcy.32 By pointing out these mechanisms in the legacies of the Colonies of Benevolence, we aim to open up further lines of inquiry regarding the contemporary relation between colonial and capitalist logics, and neoliberal technologies of social control and spatial planning.

Conclusions

What happens when Veenhuizen and the Colonies of Benevolence are approached within the context of modernity/coloniality? One answer may be that the concept of coloniality makes Veenhuizen legible as a node in a larger ideological and material network of colonial relations that functioned across the metropole and its overseas colonies. How does an account of modernity/coloniality within “domestic” histories of the Netherlands, for instance, shed light on how unemployed and poor white communities were treated in the past and on how these communities’ predominant political commitment to populist right-wing parties is currently perceived? Looking at the history of Veenhuizen shows that the oppression of these communities is partially rooted in the same colonial logic and practice that dominates contemporary racialized populations, which are constructed as existentially threatening the white unemployed and working class in the Netherlands. To speak with Stoler, our line of thinking in this contribution has been to show the types of perspectives that are produced when we no longer treat colonial phenomena “as realities of an Other moment” and space, but rather as phenomena that are “implicated (…) in the disquieting present.”33

Notes

- 1This publication emerged from the project ‘Imagining the Rural in a Globalizing World’ (RURALIMAGINATIONS, 2018–2023). This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (grant agreement No 772436).

- 2 The Colonies of Benevolence: An Exceptional Experiment, ed. Kathleen De Clercq, Marja Van den Broek, Marcel-Armand Van Nieuwpoort and Fleur Albers (Assen: Royal Van Gorcum Publishers, 2018); C.A. Kloosterhuis, De bevolking van de vrije koloniën der maatschappij van weldadigheid (Zutphen: De Walburg pers, 1981); J.J. Westendorp Boerma, Johannes van den Bosch als sociaal hervormer: de maatschappij van weldadigheid (Groningen: P. Noordhoff, 1927); “Land zonder paupers,” De ijzeren eeuw, VPRO, 30 May 2018, television.

- 3See Anibal Quijano, “Colonialidad y Modernidad/Racionalidad,” Perú Indígena 3.29 (1991): 11-20; Walter Mignolo, The Darker Side of Western Modernity: Global Futures, Decolonial Options (Durham & London: Duke University Press, 2016); María Lugones, “Towards a Decolonial Feminism,” Hypatia 25.4 (2010): 742-759.

- 4Gloria Wekker, White Innocence: Paradoxes of Colonialism and Race (Durham & London: Duke University Press, 2016), 2.

- 5Wekker, White Innocence, 25.

- 6Lisa Lowe, The Intimacies of Four Continents (Durham & London: Duke University Press, 2015), 2.

- 7Ann Laura Stoler, “Intimidations of Empire: Predicaments of the Tactile and Unseen,” in Haunted by Empire: Geographies of Intimacy in North American History, ed. Ann Laura Stoler (Durham & London: Duke University Press, 2006), 6.

- 8The Colonies of Benevolence: An Exceptional Experiment; Kloosterhuis, De bevolking van de vrije koloniën der maatschappij van weldadigheid; Westendorp Boerma, Johannes van den Bosch als sociaal hervormer: de maatschappij van weldadigheid; Suzanna Jansen, “Land zonder paupers,” in Het pauperparadijs (Amsterdam: Uitgeverij Balans, 2008), 42.

- 9Ania Loomba, Colonialism/Postcolonialism (New York: Routledge, 2015); Robert Miles, Racism (New York: Routledge, 1989), 113.

- 10Heather Grab, Bryan Danforth, Katja Poveda, and Greg Loeb, “Landscape simplification reduces classical control and crop yield,” in Ecological Applications 28.2 (2018): 348-355.

- 11Johannes van den Bosch, Verhandeling over de mogelijkheid, de beste wijze van invoering, en de belangrijke voordeelen eender algemeene armen-inrigting in het Rijk der Nederlanden, door het vestigen eener Landbouwende Kolonie in deszelfs Noordelijk gedeelte (1818), 266.

- 12Susan Legêne, “BOSCH, Johannes van den,” BWSA 8 (2001), 12-17.

- 13Ann Laura Stoler, “Colony,” in Political Concepts: A Critical Lexicon (New York: Fordham University Press, 2018).

- 14Loomba, Colonialism/Postcolonialism, 114.

- 15Jansen, Het pauperparadijs, 121.

- 16N.L. Stepan, “Race and Gender: The Role of Analogy in Science,” in The Anatomy of Racism, ed. D.T. Goldberg (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press), 43.

- 17Jansen, Het pauperparadijs, 42; Kloosterhuis, De bevolking van de vrije koloniën der maatschappij van weldadigheid, 37.

- 18“Genesis 3:17,” The Holy Bible: King James Version.

- 19J.M Coetzee, White Writing: On the Culture of Letters in South Africa (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1988), 21.

- 20Kloosterhuis, De bevolking van de vrije koloniën der maatschappij van weldadigheid, 46; Albert Schrauwers, “The ‘Benevolent’ Colonies of Johannes van Den Bosch: Continuities in the Administration of Poverty in the Netherlands and Indonesia,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 43.2 (2001): 304-5, 311-2.

- 21J.J. Westendorp Boerma, Johannes van den Bosch als sociaal hervormer, 16.

- 22Ibid.

- 23Schrauwers, “The ‘Benevolent’ Colonies of Johannes van Den Bosch,” 316.

- 24Wil Schackman, De bedelaarskolonie: De Ommerschans, het eerste landelijk gesticht voor luilevende armen (Amsterdam: Van Gennep, 2013), 310.

- 25Jansen, Het pauperparadijs, 164-68.

- 26Jansen, Het pauperparadijs, 176.

- 27Jansen, Het pauperparadijs, 175.

- 28Jansen, Het pauperparadijs, 177.

- 29Jansen, Het pauperparadijs, 178.

- 30Jansen’s specific use of “branding” raises (theoretical) questions surrounding the onto-epistemological relation between the discursive and the material. A link to Foucault’s work on biopolitics might be expected here, but he was not the first, nor the only thinker to probe questions regarding processes of subjection, subjectification, and power structures. We are indebted to the work of decolonial and anticolonial scholars Sylvia Wynter and Frantz Fanon, and their notion of sociogeny. See Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks, translated by Charles Lamm Markman (New York: Grove Press, [1952] 1967); Sylvia Wynter, “The Ceremony Must Be Found: After Humanism,” Boundary II 12.3 (1984): 19-70.

- 31Named after minister for Living, Neighborhoods and Integration Ella Vogelaar, who, in 2007, published a list of 40 residential areas considered “problem areas.”

- 32Bench Ansfield, “Still Submerged: The Uninhabitability of Urban Redevelopment,” in Sylvia Wynter: On Being Human as Praxis, ed. Katherine McKittrick, 127.

- 33Stoler, “Intimidations of Empire,” 20.

b

clustered | unclusteredAgrarian Labor as Technology of the Subject: The Dutch Colonies of Benevolence and the Maoist Sent-Down Movement1

Emily Ng

In the print below, the gentleman in the long blue coat and the top hat – perhaps a patron or supporting member of the Society of Benevolence – faces away from the viewer (Figure 1). His gaze follows the pointing arm of what seems to be the district master of Frederiksoord – the first “free” colony among Johannes van den Bosch’s Colonies of Benevolence – toward the rows of tilled land, topped by the farming colonist and his allocated cows. In the background, a series of farmhouses, distributed along parallel roads. In the near and far distance, clusters of trees, whose role in the logic of enclosure, as we will see below, is partially obscured, presented here more as a picturesque element.

.jpg)

Parallelling Dutch landscape paintings of the seventeenth century, De Kolonie Fredriksoord opens up onto an expansive cloudscape, with subdued colors awash in golden light below. The central elements are familiar: the dirt road, the trees, the farmhouse, the land. Yet, the differences are telling. Formative works like Pieter van Santvoort’s Landscape with Farmhouse and Country Road (1625) tend to depict just a few farmers on a quiet, rolling, apparently unchanging landscape with a single farmhouse or two, disavowing the major commercial land reclamation projects flattening such dune-covered terrains at the time.3 De Kolonie Fredriksoord, by contrast, is bustling with clusters of humans and livestock, proudly showcasing the transformation of the landscape through cultivation amid otherwise idyllic rural visual elements.

In this, it is perhaps more akin to Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s series The Harvesters (1565), where agricultural labor is also foregrounded. Yet, whereas The Harvesters features a life of work and leisure across seasonal cycles – not only reaping, but eating, drinking, and napping in autumn; not only hunting, but also ice skating in the winter – most of the characters featured in Fredriksoord seem to be busily toiling away – tilling, herding, sowing, transporting, surveying – under the gaze of their potential benefactors.4 It presents an industrious twist on the rural idyll, merging chronotopes of non-mechanized labor and planning, progress, and surveillance (see Stuit, this cluster).5 Indeed, the painting (along with its reprints) was used by the Society for promotional purposes to raise funds from potential patrons, and seems to share the gaze of the patron, assessing the yields of their philanthropic contribution.6

Here, an urban “sent-down” youth in a plaid button-up shirt, temporarily secured pant legs, and state-issued straw hat (Figure 2). She follows the gaze and gesturing hands of the villager, the latter marked by her “traditional” flower print shirt, embroidered apron, and shin cover-ups to keep pant legs clean during agricultural work. A voluntary prelude to the compulsory Maoist “Up to the Mountains, and Down to the Countryside” campaign of the 1960s and 1970s to transfer urban youth to the countryside (also known as the “sent-down,” rustification, or “educated youth” movement), the two figures stage an encounter between city and country. Both face the viewer but look toward a horizon beyond the canvas, in a more subtle version of the heroic “socialist-realist gaze” so common in Maoist and Soviet era imagery and cinema.7 Around them, signs of abundance: ears and ears of corn, filling baskets imprinted with “…third production team”, the basic, village-like unit of the Maoist commune system. In the medium distance, a group of men, seemingly sent-down youths, rest and gesture toward the landscape. Off in the far distance are electricity towers and a cargo ship, signaling a modernized countryside, and a Communist flag atop a cluster of homes – presumably the flag of the production team noted on the harvest baskets.

Echoing such renowned Chinese landscapes as Travelers among Mountains and Streams by Fan Kuan (960-1030), the painting features mountains, rivers, and trees, and is visually divided into three planes in a style common to earlier Chinese landscapes – near, middle, and far, stacked vertically. Yet, whereas the humans (and oxen) in landscape paintings like Travelers are known for their miniscule scale compared to the vastness of the mountains, with the nearest plane filled with detailed features of the land, most prominent in Aspiration in the Mountain Village are the two human protagonists undergoing mutual transformation. Their postures register a reversal of positions: the book-learned takes on an assured, determined, hardened stance, while the farmer gestures seem more gentle, pensive, and guiding.

Unlike nostalgic, counter-urban Sung Dynasty (960-1279) portrayals of farming, which often feature a single male farmer with his ox(en), Aspiration in the Mountain Village foregrounds the meeting between farmer and urbanite, both women.8 It presents a revolutionary rearticulation of the rural idyll: a space of transformative encounter and shared horizons, a mountainous landscape marked by emblems of the party-state, peppered with modern technologies. Part of the Maoist “massification” of audiences for artistic productions, printed posters such as this were to be widely reproduced, circulated, and viewed by the very subjects featured in the image, who were to feel interpellated by the heroic call.9

Both Fredriksoord and Aspiration in the Mountain Village thus evoke older visual motifs of natural landscapes to promote campaigns that send urbanites to the countryside. While clearly divergent in scale, setting, and design, many parallels undergird the Colonies and the Sent-Down Movement.10 Both were spurred in part by the perceived scarcity of urban employment amid industrialization, and the need to redistribute urban bodies across non-urban spaces. Both prescribed farming to city dwellers otherwise inexperienced in it. Both began as voluntary programs and ended with coerced participation. Both, many have argued, failed.11 In addition, both aimed at – or at least offered rationales based on – the virtuous transformation of the subject through embodied engagements with agrarian labor. Yet, such transformations were articulated against different ills. In what follows, I explore how these two movements differently imagined rural labor as a corporeal technology of the subject.

The Colonies: Enclosure, Autonomy, Surplus

In 1818, following the Napoleonic Wars, Johannes van den Bosch founded the Society of Benevolence, a donor-based program that would send voluntary urban poor – and soon after involuntary urban criminalized poor – into rural, internal “Colonies of Benevolence” to perform agricultural work (see Introduction, this cluster). The Colonies were imagined as a solution to an array of national problems, among them, widespread urban poverty, the need to reform communal marke land ownership for modern agriculture and the free market, and decreased access to cheap imported grain following the collapse of the Dutch East India Company.12 The urban poor would be brought to the hitherto unproductive lands of dunes and peat bogs, providing for their own sustenance rather than “idly” relying on charity.

Deploying Christian-cum-Enlightenment conflations of idleness with vice, the logics and practices of these internal colonies and those of external colonies mutually informed each other (see Bosma and Valdés Olmos, this cluster). Themes of industriousness were combined with themes of morality and autonomy, and given shape in contrast with idleness and dependency. Van den Bosch’s formulations can be understood in the context of the broader “industrious revolution” and discourses on “productive virtue,” to which poverty and idleness were increasingly tethered in Dutch rhetoric and policy, as well as in the liberalist articulations of the middle class.13 Echoing French and British liberalism, idleness was deployed in condemnations of the “idle aristocracy,” against which middle-rank “industrious classes” would define themselves as the true bearers of civilization.14 On the other end, imaginations of industrious, self-willed labor were central to the distinction between the middle-rank and proletarian “rabble” classes, who were to be excluded from new formulations of “the people.”

In line with its aim of providing poor relief through labor rather than charity, the Society’s archival photographs of the Colonies (Figure 3) showcase the metamorphosis of the so-called rabble classes into the virtuously productive “people” of an emerging civil society. Here, rows of colonists are posed atop rows of vegetation – a mutual ordering of self and land, one cultivating the other through agriculture. (But as the not-quite-perfect rows give hint to, such efforts at order often fell short of their aim.) Moreover, the visible enclosure of the colony plot by the lines of trees – minimized in Figure 1 –speaks to notions of agrarian labor inherited from John Locke’s labor theory of property, which would influence generations of liberal thinkers to come, including those in Van den Bosch’s milieu. In Locke’s writings, the centrality of reason to liberty and civil society was tied to industriousness, particularly through the dual notions of private property and agrarian labor. Articulated through a language of colonial difference, labor upon enclosed property provided at once the moral ideal and rationale for colonization. For Locke, more than in mere non-urban subsistence, the “industrious Englishman engaged in agrarian labor, defined repeatedly as cultivation, enclosure and husbandry of land,” which distinguished him explicitly from “the American Indian who is ‘idle.’”15

The right of the English colonizer to claim “wasted” land – defined as non-enclosed and non-cultivated – was thus justified through the very act of labor upon enclosed land, defined as industrious. Such “liberal colonial” justifications were not simply applied to external colonies, but would also be taken up as the premise for internal colonies across Europe and North America.16 Tree-lined views of the Colonies, in this sense, are crucial for the visual staging of the subject-in-transformation, as the very possibility of productive virtue required the transformation of an unbounded, idle wilderness into an industrious, agrarian rurality.

If the imagined movement from wilderness to cultivation was produced in part through spatial enclosure, that from coercion (as forced laborer) to freedom (as civilized citizen) was routed in part through a production of desire in the Colonies: the desire for surplus. Alongside enclosure, the visual dominance of parallel lines in the photograph resonates with capitalistic logics of surplus production through monocultural cash cropping. While the makings of autonomy for the poor through agriculture might first point to self-subsistence, the Colonies importantly aimed to teach the urban poor to produce beyond personal subsistence.

Defending himself against liberal critics of coerced labor in the Colonies, Van den Bosch proposed a theory of labor linking coercion with surplus. He argued that what critics termed “free” wage labor was, in fact, not free at all, as wage laborers were forced to hire themselves out due to their lack of access to the means of production. Far from the Marxian critique it may seem to resemble, Van den Bosch’s argument naturalizes the necessity of coercion.17 Slipping implicitly away from the particularity of “idle” populations, he suggests that coercion is needed to produce any surplus: “The foundation of all labor above and beyond that required immediately to fulfill natural needs is the result of force.”18

With urban wage labor markets in mind, rural residence at the Colonies was thus to (re)produce the autonomous, self-disciplined, commodity-producing ideals of the market—“to inculcate both capitalist work discipline and responsiveness to market incentives to crop production.”19 Copper medals, formal status, and degrees of freedom in activity were awarded depending not only on general good behavior, but on levels of production.20 Rural labor in the Colonies, in short, was designed to cultivate a rudimentary capitalistic subjectivity. Learning to want to produce surplus, the logic went, would prepare the colonists for self-sustenance in the real market, ridding the former pauper at once of idleness and dependency, paving their way toward autonomy. Tree-lined enclosures reinforced notions of agrarian industriousness and private property, while involuntary participation materialized (and paradoxically revealed) the implicit coercion structured in the so-called free market.

The Sent-Down: Encounter, Proximity, Anti-Bureaucratism

From the 1950s through the early 1970s, amid an array of other political campaigns, the Maoist administration sent waves of urban zhiqing, “educated/intellectual youth,” and bureaucratic officials to live, work, and be “reeducated” in rural regions across China. By 1968, participation became systematic and compulsory, in what came to be referred to as the “Up to the Mountains and Down to the Villages Movement.” An estimated 17 million youths would be sent to the countryside across the span of a decade, some to rural village communes, others to military and state farms.21 Whereas the Colonies centered their efforts on criminalized paupers, the Sent-Down Movement was aimed at those poised to be potential future leaders of the nation (indeed, many contemporary leaders, including the current Chinese president, were once sent-down youth).

Various lead-ups to the campaign have been proposed: concerns over rising urban unemployment, fear of political instability from the Red Guard movement, the need for agricultural development after years of rural surplus extraction to support urban industrialization, and increasing factional tensions within the Chinese Communist Party. The final notion is worth elaborating on here. Whereas Mao had long been known for his stance against excessive bureaucratization and technical specialization, a political split had grown between those who advocated technical rationality as a necessary price for development, and those like Mao who felt bureaucratization was antithetical to communist equality, as “it would make technical specialists rather than peasants the central force in society.”22

While the language of idleness – so prevalent in writings on the Colonies of Benevolence – was not absent from the Sent-Down Movement, the subject of concern differed. For Mao, rather than addressing idleness in the urban poor, agricultural labor was an antidote to bureaucratism, technocracy, and “bourgeois tendencies” among the urban educated classes. Indeed, in Maoist writings more broadly, when idleness was evoked, it tended to be attached to officials and bureaucrats:

[Bureaucratic officials] want others to read documents; the others read and they sleep… they are disinclined to do extra things… They seek pleasure and fear hardships… [their] home and its furnishings become more and more luxurious… They eat their fill every day; they easily avoid hard work.23

Beyond Weberian critiques of bureaucracy in the West, Maoist critiques of bureaucracy connoted not only their modern rationalistic manifestations, but also the Chinese imperial bureaucratic system. Of particular concern was the tendency for the imperial bureaucracy – and by extension the Communist one – to set the educated population apart and advance them at the expense of commoners.24

Paralleling the language of sending educated urban youth “down” to the countryside, the Maoist critique of bureaucratization was often articulated in terms of the distance between the “up” and “down,” where “up” was linked to bureaucratic officialdom and “down” was linked to everyday reality and the masses: “At the highest level there is very little knowledge; they do not understand the opinion of the masses… the top is divorced from the bottom.”25 What would produce proximity between the top and the bottom, in the language of Maoist policy, was the “mass line” of twofold participation: the sending of administrators and technical specialists “down” to the masses to perform basic non-specialized labor, and processes in which the masses are invited upward to participate in decision-making. Rather than Weberian bureaucratic ideals of efficiency through specialization, “skilled personnel are supposed to be willing to leave comfortable and familiar posts for terms in manual labor or work for which they have not been trained.”26

The role of agricultural labor in removing the distance between elite and lower classes, and in bringing forth revolutionary consciousness can also be understood in part through Marx’s approach to labor as an original site of alienation and class difference. If labor was to provide a theory of property for Locke, it would provide a theory of value in Marx – specifically, the production of surplus value. For Marx, surplus value was created by the embedding of manual labor into the commodity form. By the resulting concealment of the original relations of production, this congealed labor would come to be devalued in the process of capitalist exchange.27

In the context of the Sent-Down Movement, re-encounter with material production under non-capitalist conditions would thus imply a re-orientation in one’s understanding of value. Whereas the Dutch colonists were to cultivate a desire for surplus value through crop production and top-down incentives, the Chinese sent-down youth were expected to learn directly from peasantry, who were both more seasoned in agricultural work and considered by Mao to be more politically revolutionary than the urbanites.29 Alongside reeducation through agricultural labor, then, the very meeting of educated youth and peasantry was to induce transformation.30 Echoed in the visual prominence of the encounter between the two figures in Aspiration in the Mountain Village (Figure 2) as well as in photographs like this one (Figure 4), the student and the peasant would come – visually and politically – face-to-face, one learning from the other. While revolutionary reeducation was emphasized for the urbanites, the peasantry was to benefit from the book learning of the former, featured visually in the photograph by the presence of the “little red book” of Quotations from Mao Zedong.

The transformative potential of agricultural labor in the Sent-Down Movement, then, can be understood – at least at the level of political ideals – through the capacity of manual labor and encounter with the peasant to bring educated urbanites “down,” diminishing the gap between high and low, minimizing bureaucratization and specialization. At the same time, such images also obscure a central element of the plan, given their role in recruitment. The urbanites who lived in “comfort” were to grow more revolutionary in part from the difficulties of rural life. The smiling faces and resting postures, in both the photo and the poster above, heighten the sense of pleasure in revolutionary participation, while minimizing Mao’s written mentions of the harshness of rural conditions.

Rural Labor as Corporeal Technology of the Subject

Amid moral indictments of the “able-bodied unemployed” in Europe, articulations of the industrious subject in the Colonies echoed liberal discourses of productive virtue: the working body would become a moral, self-disciplined body.31 Moreover, the allocation of family farms and the production of “simple” commodities would not only offer practice in private land ownership and voluntary self-willed labor – central to Lockean formulations of civil society – but also produce desire for surplus value perceived as lacking among the idle poor.

By contrast, portraits of the revolutionary subject in the Sent-Down Movement implied a Marxian labor theory of value and Maoist articulations of two-way participation. Given political indictments of bourgeois tendencies among urban educated classes, the laboring body was rendered a revolutionary, politically rectified body. For increasingly technocratic classes, participation in collective agriculture and the encounter with peasantry and the harshness of rural life were to diminish the distance between mental and manual labor, between upper and lower classes.

Divergences between the two campaigns are echoed in their imagistic counterparts. While both take up older landscape motifs familiar to their viewers, Maoist era posters and photographs feature the encounter and merging of roles between educated urbanites and peasantry. Images of the Dutch Colonies feature the enclosure of orderly land, the emergence of industrious virtue among the relocated urban poor, and the gaze of patrons. In short, the same corporeal technology – agrarian labor – was taken up to produce two contrary subjects.32 In the Colonies, rural labor was to produce a moral, industrious, proto-capitalist working body, through the instillation of desire for surplus value. In the Sent-Down Movement, it was to produce a revolutionary, anti-bourgeois laborer, through contact with harsh conditions, manual work, and the peasantry.

Notes

- 1This publication emerged from the project ‘Imagining the Rural in a Globalizing World’ (RURALIMAGINATIONS, 2018–2023). This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (grant agreement No 772436).

- 2Every effort has been made to obtain permission to use all copyrighted images reproduced in this contribution. Nonetheless, whosoever believes to have rights to this material is advised to contact the research team.

- 3Ann Jensen Adams, “Competing Communities in the ‘Great Bog of Europe’: Identity and Seventeenth-Century Dutch Landscape Painting,” Landscape and Power, ed. W.J.T. Mitchell, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994), 35-76.

- 4Not to mention more satirical depictions by Pieter Bruegel the Elder and others of peasantry drinking, brawling, and gambling. See Carla Brenner, Jennifer Riddell, and Barbara Moore, Painting in the Dutch Golden Age: A Profile of the Seventeenth Century (London: National Gallery of Art, 2007).

- 5Bakhtin describes the idyllic chronotope as one that builds on folkloric time, which grafts cyclical time onto a self-sufficient space that presumes a lack of intrinsic links to the rest of the world. In the agricultural idyll, unmechanized agricultural labor becomes the central link between humans and nature. For Bakhtin, the arrival of the capitalist world marks the chronotopic destruction of idyllic worlds, through the entry of progressive history and alienated labor. (M. M. Bakhtin, The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1983), 224-234.) In Fredriksoord, idyllic landscape features and unmechanized labor are joined by elements of rational panoptic planning (e.g., the parallel houses), and the collective dimension of labor together with the gaze of the visitors introduce a link to the urban capitalist world.

- 6Usage of the image for promotional purposes to patrons was confirmed through personal communication with the current archivists at the Society of Benevolence.

- 7Stephanie Hemelryk Donald, Public Secrets, Public Spaces: Cinema and Civility in China (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2000), 62.

- 8Scarlett Ju-Yu Jang, “Ox-Herding Painting in the Sung Dynasty,” Artibus Asiae 52.1/2 (1992): 54-93.

- 9Christine I. Ho, “The People Eat for Free and the Art of Collective Production in Maoist China,” The Art Bulletin 98.3 (2016): 348-72.

- 10Another Chinese program that had its parallels with the Colonies, particularly the unfree ones, was the “Reform through labor” program, which constituted a penal system of forced labor camps, both urban and rural. I focus on the Sent-Down Movement due to its explicit focus on rural labor, and its slippage between volunteerism and coercion. But, as Stuit argues in this cluster, the Colonies precisely utilize the rural to conceal their carceral dimension.

- 11In the Colonies, harvests were disappointing “right from the start,” the colonists “turn[ed] out to eat more than had been estimated,” and paid membership remained lower than expected (The Colonies of Benevolence: An Exceptional Experiment, ed. Kathleen De Clercq, Marja van den Broek, Marcel-Armand Van Nieuwpoort, and Fleur Albers (Assen: Koninklijke Van Gorcum, 2018), 30, 33). In the Sent-Down Movement, villagers resented the sent-down youth for taking up resources of food, shelter, and supervision without being able to contribute sufficiently, and many sent-down youths resented their lives in the countryside, even if some were initially enthusiastic. Given the scale of the Sent-Down Movement – around 17 million persons – a “lost generation” of urban youth was formed, most of whom did not get the chance to attend university as they would have in the city (Helena K. Rene, China’s Sent-Down Generation: Public Administration and the Legacies of Mao’s Rustication Program (Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press, 2013)).

- 12Colonies of Benevolence, 14-15.

- 13Elise van Nederveen Meerkerk, “Industriousness in an Imperial Economy: Delineating New Research on Colonial Connections and Household Labour Relations in the Netherlands and the Netherlands Indies,” Workers of the World: International Journal on Strikes and Social Conflicts 1.3 (2013): 102-117, 107; Siep Stuurman, “The Discourse of Productive Virtue: Early Liberalism in Europe and the Netherlands,” Under the Sign of Liberalism: Varieties of Liberalism in Past and Present (Zutphen: Walburg Pers, 1997), 33-45; Jan de Vries, The Industrious Revolution (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008).

- 14Stuurman, “The Discourse of Productive Virtue,” 33-45.

- 15Barbara Arneil, “Liberal Colonialism, Domestic Colonies and Citizenship,” History of Political Thought 33.3 (2012): 491-523.

- 16Arneil, “Liberal Colonialism, Domestic Colonies and Citizenship,” 479.

- 17Albert Schrauwers, “The ‘Benevolent’ Colonies of Johannes van den Bosch: Continuities in the Administration of Poverty in the Netherlands and Indonesia,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 43.2 (2001): 300.

- 18Van den Bosch (1851: 316), cited in Schrauwers, “The ‘Benevolent’ Colonies of Johannes van Den Bosch,” 305.

- 19Schrauwers, “The ‘Benevolent’ Colonies,” 310-311, 314.

- 20Windt, cited in Schrauwers, “The ‘Benevolent’ Colonies,” 309-310.

- 21Yihong Pan, Tempered in the Revolutionary Furnace: China’s Youth in the Rustication Movement (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2009), 48.

- 22Rene, China’s Sent-Down Generation

- 23Zedong Mao, “Twenty Manifestations of Bureaucracy,” Selected Works of Mao Zedong, v. IX (Hyderabad, India: Sramikavarga Prachuranalu, 1994), 430-431.

- 24Martin King Whyte, “Bureaucracy and Modernization in China: The Maoist Critique,” American Sociological Review 38.2 (1973): 149-163.

- 25Mao, “Twenty Manifestations of Bureaucracy,” 429, 432.

- 26Whyte, “Bureaucracy and Modernization,” 155.

- 27Karl Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, v. I, in The Marx Engels Reader, ed. Tucker (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1978).

- 28Photo published in online edition of Chen, Minnie (2013), “Premier Recalls Major Turning Point for Nation.” South China Morning Post, 18 March, 2013.

- 29This is in part based on a Maoist articulation of revolutionary attitude, in which direct participation in labor, little to no buying of others’ labor, and experience of poor living conditions – qualities characterizing what Mao termed poor and lower-middle peasants – marked one “more” revolutionary on a spectrum from poor peasant to landlord. See Zedong Mao, “Analysis of the Classes in Chinese Society,” Selected Works of Mao Zedong, v. I. (Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1965), 13-22. See Colonies of Benevolence, 33 on the lack of experienced farmers in the Colonies.

- 30Unlike the official separation of the Colonies from surrounding villages, sent-down youth were incorporated into existing rural communities (with the exception of those sent to military and state farms).

- 31James Mavor, “Labor Colonies and the Unemployed,” Journal of Political Economy 2.1 (1893): 26-53.

- 32I am thinking here of Foucault’s earlier works on technology as a micro-physics of power that produces the subject in the service of modern discipline, as well as his later works on technologies of the self as a site of ethical possibility. See Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (New York: Vintage Books, 1995) and The Care of the Self (London: Penguin, 1990). In this sense, even as agrarian labor is deployed to realize various forms of modern power, its potentiality as a medium for ethical transformation is not foreclosed.

c

clustered | unclusteredThe Carceral Idyll: Rural Retreats and Dreams of Order in the Colonies of Benevolence1

Hanneke Stuit

In Domestic Colonies: The Turn Inward to Colony, Barbara Arneil draws attention to the need to see external and domestic colonization in conjunction. Both forms of colonization are part of a transnational network of ideas and practices that profoundly influenced the course of history on domestic and foreign soil. One of the material starting points of the spread of domestic colonies, Arneil makes clear, needs to be pinpointed in Drenthe, a rural area in the Northeast of the Netherlands, where the Society of Benevolence opened Frederiksoord, its first trial colony, in 1818.2 For Arneil, agricultural labor is a defining principle of domestic colonization that is often overlooked, obscuring “that colonization could be characterized as non-punitive, agrarian and domestic in form rather than as exclusively carceral, punitive and external.”3 Colonization and the countryside are indeed joined at the hip, and not just in domestic cases. As Raymond Williams has argued, imperialism is one of the “latest models of ‘city and country’” in which, in the case of industrial Britain, “distant lands became the [new] rural areas” feeding the “home” country.4 However, as Ann Stoler points out, the pedagogic, non-punitive aspects of agricultural colonial labor cannot be regarded as separate from the “programs and practices of incarceration” by which they were “continually ‘contaminated.’”5

Arneil’s insistence on the link between agriculture and colonization is extremely relevant in this matrix of pedagogy and punishment, especially in the case of the Colonies of Benevolence. As the following close reading of visual renditions of Frederiksoord makes clear, the consideration of the role of agrarian aspects in colonial imaginaries should, in fact, be extended to include the symbolic and ideological effects of colonization’s reliance on the rural idyll. Without taking account of the rural idyll, I argue, the Colonies’ dreams of social order – which persisted much longer than the Society’s continuous financial floundering6 would lead one to expect – cannot be properly understood. I will show how the rural idyll and these nineteenth-century dreams of social control together formed what I call a carceral idyll. In this carceral idyll, rural order equals “good” discipline, and the exile of thousands of vagrants and orphans to the countryside – amounting to the largest internal migration in Dutch history7 – is posited as picturesque.

Carceral Idylls

What most idylls – whether carceral, rural, pastoral or provincial – have in common is that they revolve around a restorative desire for a “unitary, cyclical, pre-capitalist form of folkloric time that binds a small community to a fixed, familiar, isolated place where its members follow in the footsteps of their ancestors”8 and these members collectively work for the benefit of the common good.9 Carceral idylls, I argue, tie this restorative desire to the correction of a normative life gone astray. This results in a cyclically imagined return to normalcy, in which the process of repair is also inflected with ideas of linear progress. On the one hand, carceral idylls thus lean on the collectively and ancestrally rooted subject that Mikhail Bakhtin poses as central to many forms of the idyll. On the other hand, they endorse the subject produced by Foucauldian discipline, in which an individual is supposed to improve over time. This Foucauldian subject is singled out in comparison to normative others in order to be relegated to the realm of the excluded – a double technique of “binasry division and branding (mad/sane; dangerous/harmless; normal/abnormal)” that opens the route to the exercise of “the universality of disciplinary controls” on the branded subject in an individual way.10

Carceral idylls are idylls precisely because they focus on the isolation of the subject to a place where time works differently, a “stillness” or “ekstasis” that is deemed necessary to achieve linear progression and restoration to “normalcy.” Carceral idylls involve experiences, scenes, and incidents of incarceration that can never last, yet persist in idealized forms. Although often associated with criminalized others and the narratives of rehabilitation and moral redemption that come with notions of imprisonment, such carceral idylls are not limited to criminals or the penitentiary.11 Many cultural expressions, such as Prison Break or Orange is the New Black, depict socially privileged groups that are not likely to come into contact with incarceration and focus on scenes of escape into exceptional individuation. These scenes should be read as a whitewashing of the more sinister “dreams of order”12 associated with the disciplinary response to fears of confusion and contagion theorized by Foucault. This whitewashing is also present in carceral idylls that feature the idealization of the prison cell as a place of refuge and monastic contemplation;13 the exoticization and idealized representation of criminals and prison environments;14 and the notion that imprisonment can be humane, as long as the prison is “properly” designed and organized.15 In many of these cases, the carceral idyll obscures the fact that it (re)creates the very subjects it seeks to cleanse, and enforces differentiations between mad and sane, dangerous and harmless, and normal and abnormal people.

In the Colonies of Benevolence, the carceral idyll manifests through a mix of the Society’s dreams of control and progress through social engineering on the one hand, and its mobilization of the rural idyll on the other. In its idyllic view, placing groups of stigmatized people in an isolated and controlled setting where they perform agricultural labor and spend time “outdoors” is considered inherently redemptive of both people and land (see Bosma and Valdés Olmos, this cluster), while the charitable members who pay contribution to the Society16 are helping to uplift the Dutch economy and its poor population. The ways in which the carceral idyll entwines dreams of order, and its attendant desire for progress and rehabilitation, with the rural idyll is clearly visible in the materials used to promote the concept of the Colonies.

Greetings from Frederiksoord

This promotional map centralizes the spatial organization of the Colonies in the vicinity of Frederiksoord. It includes different neighborhoods of the “free” colonies of Willemsoord, Westvierdeparten, Wilhelminaoord, Oostvierdeparten and Boschoord (colony VII on the map), but conveniently leaves out the two so-called “unfree” colonies: De Ommerschans and Veenhuizen. These penal colonies were erected in 1819 and 1823 respectively to house vagrants, beggars and cumbersome colonists. Without the penal colonies, the map appears as highly idyllic, resembling a tourist postcard that could have read “Greetings from Frederiksoord.”17 The map has a “villagey” feel that relies on the rural idyll’s treatment of the village as “a safe, sedate, simple little world offering happiness and comfort.”18

Visitors to the Colonies were not uncommon and the map communicates its potential as an attractive destination by depicting the Colonies’ traveler’s accommodation in the top right corner. Overall, the idyllic setting is emphasized by the soft lines of the sketched landmarks, the decorative use of flowers, and the depiction of the small drawbridge near its logement (lodgings). The Colonies’ goal of moral uplift through labor, sustenance, housing, and education is also made part of the idyllic encasing.19 The map foregrounds education by depicting its three schools (of Forestry, Agriculture, and Horticulture) and highlights the Society’s investment in innovation, connectivity, and progress by showing off the horse-drawn tram between Steenwijk and Frederiksoord.20 The inclusion of an image of Rustoord, a retirement home for colonists and the Netherland’s first fully-funded old people’s home, also testifies to the Society’s idealistic intentions.

The Colonies’ industriousness is emphasized by including the basketry and featuring three farms, referencing its agricultural basis. One of these images – circled in figure 1 – jumps out visually because it is placed at an odd angle, making it more difficult to read than the others. Here is the photograph on which the drawing is based:

This photograph, although peripheral and tilted on the map, depicts the intended core of the Colonies’ internal economy. It shows a standard-issue farm for colonists. The farm, its inventory, the colonists’ clothes, one or two cows and some sheep, were all provided by the Society on loan. In exchange, the Society withheld part of the salaries colonists earned during the collective labor they performed on the fields and in the factories for four or five days a week.21 The rest of the week, the colonists worked their own plot of land around their small farm, with the harvest going directly to the Society for the alleviation of the colonists’ debts.22 Each farm was inhabited by a family consisting of two parents and their children to work the land (the boys) or the weaving mill (the girls). Retired colonists were expected to move out, and if one of the parents was widowed and did not find a new spouse, or if a family did not have enough children to ensure the upkeep of the farm, they would be supplemented with single young adults or orphans selected by the Society of Benevolence.23 In this way, the Colonies aimed to be self-sustaining and even profitable within sixteen years of their inception.24 However, when harvests were disappointing and most colonists failed to cover their debts, the Colonies increasingly moved towards a punitive system.25

The photograph privileges the idea of the farm rather than its actual workings, just as it is about the idea of the people it depicts rather than about who they actually are. The image has been archived without a date, exact location or names, and the three colonists are clearly posing for the camera. The man with the pipe on the left is placed in the midst of the foliage he is supposed to tend to and spectrally fades into it. The figures on the right more readily draw our gaze due to their striking white clothing, but they, too, are awkwardly placed. The man in the middle, whose expression is concealed by his hat, stiffly holds a spade that idly hovers in the air. He is not standing anywhere near soil that needs to be turned over or dug out. The woman on the right, who seems liveliest because of her visible smile, functions as a token of the fact that all is as it should be on this family farm. These people, in their collective role of performing agricultural labor, are props belonging to the timeless idyll of the small-scale, self-sustaining farm – an idyll that sits awkwardly with the emphasis on the technological innovation the Society deemed necessary from the outset for the production of cash crops for the national market.26 In this sense, the photograph stages a myth of the “tradition of ‘self-help’ in rural communities,” where people take care of themselves and each other without external interference.27 It evokes Bakhtin’s idyllic chronotope in “the positively valued image of ‘primitive man’ existing ‘in the collective consuming of the fruits of his labor and in the collective task of fostering the growth and renewal of the social whole.’”28 However, the head of this family is not, as J.M. Coetzee argues of the colonial pastoral in South Africa, a “benign patriarch” 29 ruling his own little kingdom, but a serf in the “closed corporate village” of the carceral idyll.30

Cells and Walls; Farms and Trees

In the print above, depicting Frederiksoord in its inception phase, rows of farms stretch and fade into the distance. The print suggests two ideas at once: Frederiksoord is supposed to resemble a village that holds the promise of “tightknit, homogeneous communities” of self-sustaining farmers, but the farms on which individuals are supposed to thrive are ordered disciplinarily along perpendicular lanes that explicitly facilitate surveillance.31 Despite its lack of walls, Frederiksoord is laced with a carceral dimension as it echoes Jeremy Bentham’s principles of social engineering through spatial organization, and closely resembles the penitentiaries from which it tried to distance itself so emphatically.32

There are also differences, however. The famous panoptic tower, or any analogous center from which the principle of discipline can be initiated and maintained through a structural (if often unoccupied) center of vision, is presented peripherally: a center resembling a town square, with the director’s house, the school, and two filatures, occupies a corner of the print. According to the Cambridge French-English Dictionary, the word filature refers to a spinning mill or a factory in general, but it can also denote surveillance in the form of shadowing someone. Indeed, even though the seat of power and industry seems placed on the fringes, the print reinforces a centralized bird’s eye perspective with unavoidable panoptic overtones. In this view, the four buildings on the square are uniform and require the legend on the bottom left to communicate their purpose to the viewer. No such explanation is necessary, however, for the farms, which are apparently self-evident. The “cells” of farms in the foreground are rendered in detail, each of them producing a different crop, reflecting the carceral idyll’s reliance on the continuous shuttling movement between branding excluded subjects as a group, and singling them out for individual discipline. In this way, surveillance is visually downplayed and agricultural elements seemingly dominate the scene – a tension that drives home how rural idylls and dreams of order converge into a carceral idyll in the Colonies.

Crucially, the legend emphatically mentions that the planting of trees in Frederiksoord was under way by the time the print was made, suggesting that the colony would not really be complete without them. Once planted, they would provide Frederiksoord with a rustic lushness in line with the demands of the rural idyll. This lushness is deeply colonial because the trees also set apart the Colonies’ fields as enclosed plots of land that require industrious labor to reach their full potential (see Ng, this cluster). As the trees grow, they will function as walls that make the farms less visible from the road. On the one hand, they isolate everyday life in the “cell” of the individual farm and thereby reinforce the ideological construction of these farms as mythical locales of familial and morally upright self-sustenance. On the other hand, as walls, they also keep the inhabitants of the farm in place. The people on the farm cannot see when they will be visited by the clergy or by management, which underlines the panoptic carcerality evidenced by the bird’s eye perspective in the print. In this sense, the trees function as cyphers for the rurally inflected carceral idyll that I have also tried to make visible in the images analyzed above. To my mind, this conjunction of the rural idyll with dreams of panoptic order explains how the carceral structure of exiling the poor to the countryside so that they can be molded into disciplinary subjects by the Society of Benevolence, is neglected, even when looking back on this period today. Instead, the Colonies are often presented as rural retreats in which the uncomfortable structures of oppression and suffering that characterize the entanglement of domestic and external colonization are thrown over the fence of history, as if such legacies could safely be relegated to the past.

Notes

- 1This publication emerged from the project ‘Imagining the Rural in a Globalizing World’ (RURALIMAGINATIONS, 2018–2023). This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (grant agreement No 772436).

- 2Barbara Arneil, Domestic Colonies: The Turn Inward to Colony (Oxford: University of Oxford Press, 2017), 160.

- 3Arneil, Domestic Colonies, 160.

- 4Raymond Williams, The Country and the City (New York: Oxford University Press, [1973] 1975), 279-280.

- 5Ann Stoler, “On Archival Labor. Recrafting Colonial History,” Diálogo Andino 46 (2015): 153-165. See also Kodwo Eshun, “‘The Colony is a Prison:’ Richard Wright’s Political Diagnostics on the ‘Redemption of Africa’ in the Gold Coast,” 16 December 2017.

- 6The Colonies of Benevolence: An Exceptional Experiment, ed. Kathleen De Clercq, Marja Van den Broek, Marcel-Armand Van Nieuwpoort and Fleur Albers (Assen: Royal Van Gorcum Publishers, 2018), 33.

- 7Wil Schackmann, De Strafkolonie. Verzedelijken en Beschaven in de Koloniën van Weldadigheid, 1818-1859 (Amsterdam: Atlas Contact, 2018), 28.

- 8Esther Peeren, “Villages Gone Wild: Death by Rural Idyll in The Casual Vacancy and Glue,” in Rurality Re-Imagined: Villagers, Farmers, Wanderers, Wild Things, ed. Ben Stringer (Novato: Applied Research and Design Publishing, 2018), 66.